© Francesco Longenecker / Allison Galgiani

The Kohinoor was not gifted to Queen Victoria. It was taken at gunpoint from a young ruler who had no option but to surrender it. This was part of the routine colonial plunder of India. Whether we should have it back is another matter. The Natural History Museum in Delhi has just been gutted by fire and six storeys of irreplaceable treasure destroyed. Great historic buildings in Kolkata and other cities are in a state of filth and decay. School children are not taken to see the jails where those who fought for freedom from British rule were imprisoned for years, as South African children are taken to the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, to learn how courageous South Africans fought against apartheid. The railway station at Pietermartizburg, where a young Gandhi was thrown out of the train for refusing to quit the “whites only” compartment he was occupying, is pristinely preserved with its original look and ambience. Why do Indians make rubbish of their historic landmarks? Why can’t we cherish and pass on our recent proud history?

And there are other questions. Why has the militant war cry of “Hindutva” replaced the varied and civilized heritage of Hinduism? Indian civilization has survived precisely because the fresh winds and tides of different cultures have met and flourished on this soil. Far more than survival, it has been strengthened, enriched and invigorated by this history of cross-fertilisation. It is now being shrivelled, shrunk, and dwarfed by “Hindutva” into a divisive political policy which makes nonsense of true religion and, by excluding all other Indians, threatens the meaning of India. In a 21st century democracy, does the state have the right to give itself a religious identity by calling itself a “Hindu rashtra”? Can any land mass called a country have a religion? Isn’t it people who have religions and, in this country, many religions? If religion has any place in politics, it can only be in terms of how Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest Hindu of our time, described it: “To the poor man, God is a loaf of bread.”

The new militancy extends its tentacles to all walks of life, demanding conformity of belief, which human nature has refused to bow down to since time began. All attempts to impose it have failed. The order to all Indians to shout “Bharat Mata ki Jai” is one such absurd attempt, as is the idea that those who do not conform to what “Hindutva” lays down are anti-national. Those who pose as nationalists today were nowhere in sight when nationalism was needed, during the thirty years of the Gandhi-led fight for freedom. They were safe and comfortable in their homes, supporting British rule while other Indians faced lathis and bullets and jail. It was the Hindu Right, embodied by the Hindu Mahasabha and its think-alikes, and the Muslim Right, embodied by the Muslim League who, by their support of the British Raj, together laid the ground for the partition of India. Even the Hindutva icon, Savarkar, begged for his release from Port Blair, and promised to serve the British government in whatever capacity they asked him to, in return for his release. It was a promise he then fulfilled.

What need is there to call for nationalism now, when we have been a nation for nearly seventy years — no thanks to the Hindu and Muslim Right? As for “Bharat Mata ki Jai” — if it is imposed as Heil Hitler was on Germans — no self-respecting Indian will be browbeaten or bullied into this or anything else. Again, “Hindutva” has arrived on the scene rather late. I recommend that its enthusiasts read the chapter in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India in which he describes the emotional give-and-take between himself and the men and women he met in rural areas as they talked about the meaning of this slogan, and the importance of raising it at a time when Bharat Mata was under the British stranglehold. The danger of raising such slogans today is that they endorse a belief in “my country, right or wrong”. One cannot be blindly (or hysterically) devoted to a country. A country can take the wrong road, as many have done, as ours has also done. A country is a work in progress, and there is a constant need for its people to judge it critically, and change it where change is required. The worship of motherland or fatherland is an unhealthy, fascist idea. No democratic country demands country-worship.

Recently, the HRD Minister appointed a panel whose report has recommended the study of Sanskrit in institutions of science and technology, including the IITs, so they can discover the science in ancient Sanskrit texts. The chairman of the panel, Mr. N. Gopalaswami, is a believer in astrology, as many of us are, but we don’t head panels concerned with science. Indian scientists are asking: If ancient texts have to be studied for evidence of science, why not study Tamil texts too? And how about the science that might be discovered in Pali? Meanwhile, science as it is understood in the modern world has been dealt a mortal blow by a cut of funding to the IITs — and maybe to higher education as a whole — by the Education Minister and the NDA government in its 2016 budget. Is Ms. Irani then following in the footsteps of Pakistan’s Zia-ul Haq, who made knowledge of the Koran and sharia a requirement for appointment to faculties in the sciences? RSS appointees have already been placed at the head of our premier educational and cultural institutions. And doesn’t all this remind us yet again of the continuing think-alike mindset of the Hindu and Muslim right wing, and the continuing close embrace of extremists of whatever religion?

The glitter and glamour of technology rule today’s Indian climate. Listening to the Prime Minister’s eloquent election speeches, the practised cadence of his sentences, his elegantly clad image multiplied and magnified by three giant technicolor screens in the campaign that brought him to power, I was reminded of a very different scene: a scrawny old man in a loincloth, sitting on the ground, speaking his Gujarati-accented Hindi in a voice that did not carry far, at a time when microphones didn’t always work. Yet that man galvanised Indians to fight for freedom. His message of non-violence inspired the struggle for civil rights in America, spread to Suu Kyi’s fight for democracy in Myanmar, to the young and old who formed human shields against Israeli tanks in Palestine, to the great Nelson Mandela when, after the defeat of apartheid, he created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission instead of pursuing vengeance against those who had robbed him of half a lifetime. And I thought to myself, why is Gandhi considered our past when he is so much a part of the entire world’s present? Is he not, in fact, the future, of India and the world, and the only answer to hatred and violence? It will take a young Indian leader, committed to non-violence, and to the inclusiveness that defines India, to complete the azaadi-barabari and other human rights guaranteed by our Constitution. For such a leader, religion will mean bread and water and dignity for the mass of India’s forgotten people.

First published in the Tribune, May 2, 2016.

More from Nayantara Sahgal on our website: “Writing the Age” (March 2016), “Reject Hindutva, Embrace Insaniyat” (January 2016), and “The Unmaking of India“, a statement made by the author when she returned her Sahitya Akademi award in October last year.

![]()

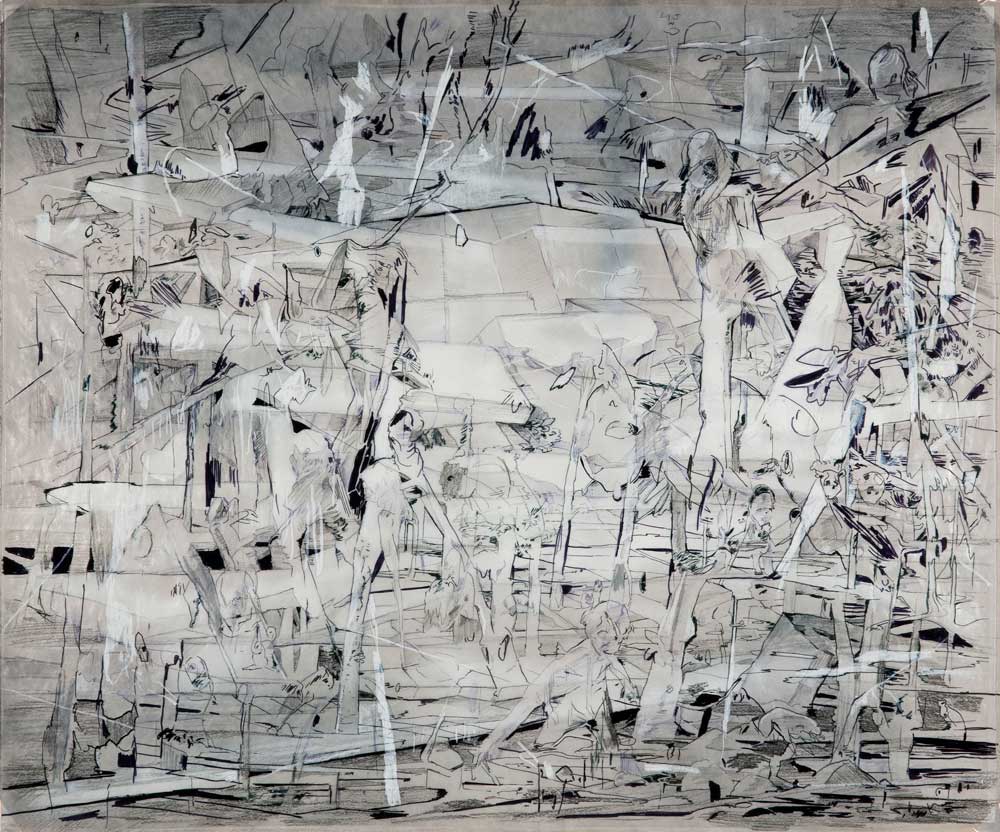

A mural at Ajanta / Kevin Standage