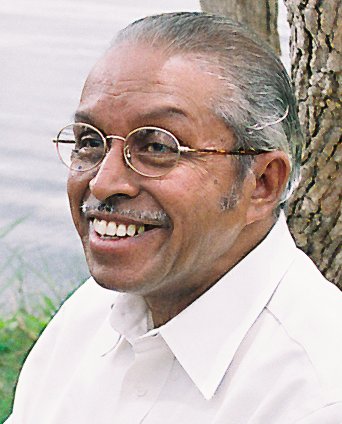

Kesari Balkrishna Pillai, one of Kerala’s foremost critical thinkers had once observed that Malayalees enjoy poetry primarily through their ears. The late ONV Kurup’s popularity depended partly on the auditory appeal and easy accessibility of his lyrics, and partly on his consistent engagement with social issues. He was a progressive among the romantics and a romantic among the progressives, though his romanticism had been tempered with classical rigour in some of his later poems, especially the book-long narratives like Ujjayini and Swayamvaram. He belonged to a generation of progressive poets who also included P. Bhaskaran and Vayalar Ramavarma. But he went ahead of both of them in terms of the range of his concerns, as well as the aesthetic appeal of his poetry to a generation brought up on a romantic sensibility pioneered by the likes of Changampuzha Krishna Pillai.

ONV, as he is popularly known among his readers, was born in a seashore village when Kerala- though the State was yet to be born, divided as it had been into Kochi, Tiruvitamkoor and Malabar –was in turmoil. A democratic transition was on inspired by egalitarian ideals. It was a period of community reform, anti-Colonial awakening and worker’s struggles. His father was a Sanskrit scholar and a disciple of Sree Narayana Guru, the great Saivite philosopher and egalitarian social reformer who had emerged from a ‘backward’ caste and gained universal acceptance as a forerunner of Kerala’s renaissance. Awakened into poetry by the music of the sea, the rustle of coconut leaves and the songs of fishermen and workers, ONV was also inspired by the humanitarian ideals of Kerala’s social reformers (some of whom were also poets of note) like Sahodaran Ayyappan, Ayyankali, K.P. Karuppan, Kumaran Asan ,V.T. Bhattathirippad, Premji and E.M.S. Namboodirippad, besides of course Narayana Guru himself. In a memoir he has stated that his early influences were Thunchath Ezhuthachan, the writer of the Malayalam Adhyatma Ramayana and Valmiki and Kalidasa who taught him that poetry should be spontaneous (swayambhoo), melodious and harmonious ( sruti-laya samanvitam), mundane ( loukiki) and aim at the welfare of all (kalyani). But it is clear that his early poetry was also inspired by Malayalam poets like Changampuzha Krishna Pillai. He tried to de-Sanskritise the idiom of Malayalam poetry encouraged by folk traditions and had a clear social vision form the very beginning that drew its stimulus from both Gandhi and Marx like the other poets of the ‘pink decade’. His travels gave him a sense of the oneness of nature and human beings. He remarked in an interview that the poplar tree of Tolstoy’s Yasnaya Polyana, the magnolia of Tagore’s Vishwabharati and the Tree of Life on the desert of Bahrain share a rare sisterhood. His many popular poems on nature and earth, like Bhoomikku Oru Charamageetam (An Elegy for the Dying Earth) and Suryageetam (The Sun-Song), are inspired by an intense love of earth and nature. Though not a modernist himself, he did learn some lessons from the next generation of poets especially about the use of free verse and fresh imagery in poetry.

Though he did pass through a period of disillusionment in the 1960s when the Communist Party got divided, he regained his hope from his essentially humanist ideals. Though he believed that ‘nightmares fluttered over us’ and he was disturbed equally by the felling of a tree, a rape or the explosion of a bomb, he found his ultimate solace in poetry by turning the collective sorrows of the society into his personal grief. His poetry retained its sensuousness to the end, but he also gained greater control over his emotions as he matured over the years. He qualified poetry as a bridge to truth, as a pearl perfected by hard labour over time until the shell is broken and it becomes common possession; as pain that inhabits the anthill of silence to meditate over the meaning of existence and as the sunbeam that illuminated his childhood solitude. ONV’s poetry is an archive of the rhymes and rhythms of Malayalam; he has several poems on music and musicians, like “A Song for Orpheus”, “To Paul Robeson”, “The Sixth Symphony”, “Tansen”, “The Bauls”, “The Moonlit Sonata” and “Mushaira”. His poetry constantly invokes Kerala’s landscapes, sounds and historical memories. He always dreamed of a new world order free from all forms of hierarchy including caste, class and gender. Woman appears in his poetry not as a personification of Eros as in many romantic poets, but as a metaphor for a genuinely human culture. He had great concern for environment and maintained his subaltern vision even while writing poems based on myths and legends like his longer narratives. He celebrates freedom in poems like “The Song of the Black Bird”, “O, Black Sun”, etc., and celebrates nature in several other poems on rivers, birds, berries and trees. In the long poem Snehichu Teerattavar (Those Who Haven’t Finished Loving) addressed to his partner, who was also his student, he says, ‘Let’s grow immortal through love and become spirits of infinite bonding’ . ONV’s poetry resolves the binaries of individual and society, nature and human being, instinct and civilization, family and the world, and considers the human beings as the measure of everything, though this anthropocentrism does not in any way turn into hubris that leads to techno-fascism that believes in ‘conquering’ nature and leads to tyranny of every kind. No one can accuse ONV Kurup of inconsistency as he has, throughout his career, maintained his faith in nature, freedom, progress, equality and love.