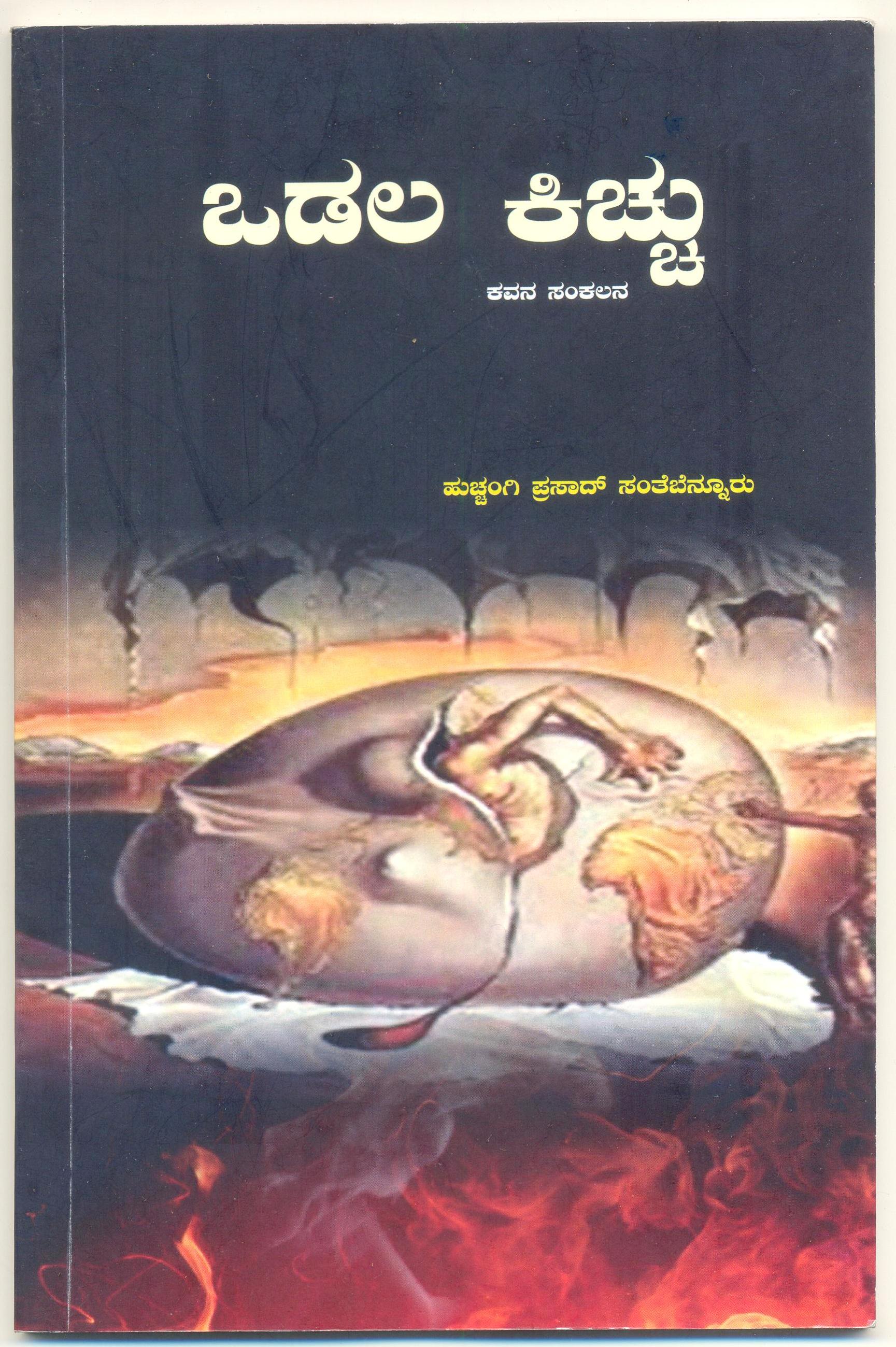

Huchangi Prasad is a twenty-three-year-old journalism student in Davenegere, Central Karnataka. Last year, he published a collection of poems called Odala Kicchu (The Fire Within) — which describes dalit lives, and issues a challenge to the continuing violence, as well as day-to-day discrimination against dalits. After his book was published last year, Prasad was attacked by Hindutva goons. He managed to escape, mainly because his attackers were drunk. Later, he would say, with great courage, that he will continue to write about and against caste.

On January 20th, before a panel discussion on Caste, Religion and Lived Experience organised by the Indian Writers’ Forum at Ambedkar University, the IWF presented a small one-time scholarship award to Huchangi Prasad thanks to a donation made for the purpose by Latha Viswanathan. After the presentation, Prasad joined his peers — the young members of the editorial collective of the Indian Cultural Forum and Guftugu, for a conversation. Here, they write of their impressions after their discussions with Prasad.

Huchangi Prasad’s first book of poems was published in April last year. Prasad is a Master’s student in Journalism at Davangere University. In October he was taken from his hostel by a group of men and attacked. They threatened to cut off his fingers if he wrote another word. This was barely two months after the murder, still unsolved, of Kannada writer and scholar M. M. Kalburgi in Dharwad. Prasad filed a police complaint, and believes from the men’s statements that they were members of the everywhere-you-look Sangh Parivar.

“The people who attacked me were drunk. They said why are you connecting being a dalit or devdasi to Hinduism?” The young poet and student is talking to a group of us IWF interns at the India International Centre, all sun and mist this morning, with ethnic-chic passersby struggling to conceal their curiosity. Our conversation is possible only because a friend has agreed to translate—in fact, become—the Kannada-English exchange.

We ask Prasad about Rohith Vemula. They had spoken on the phone; he was a comrade. “Rohith and his friends instilled confidence in me, saying the RSS is attacking all those who study or write about solidarity.” Today the politics of solidarity must weigh heavily on everyone’s mind, and Prasad is clear about the nature of the double bind. He underlines the role played by Vice-Chancellor Appa Rao (himself a former ABVP member) in Rohith’s death. He recalls Ambedkar’s focus on gender justice and women’s rights, and quotes a Kannada saying to the effect that “Only one who gives birth knows the pain of childbirth.” The words seem to me a reaching out, without compromise. Will our children one day hold hands as equals, without shame or wonder?

To a question about support from other student struggles, he responds with the flicker of a smile. “We have to decide who among (our purported well-wishers) are genuinely for us.” And he reminds us of the Sangh’s own dilemma: that “the RSS, ABVP and so on are trying to co-opt dalit struggles, but are guided by brahminical thinking … Brahminical forces have all throughout distorted history and created a mythology.”

Later in the day Prasad will address a large crowd of students at Ambedkar University, saying, “I am the son of a devdasi. My mother’s name is Yashodhamma and my father’s name is not known … There is untouchability by day but they knock on our doors at night.” In our rather smaller setting he tells us simply, “It was the oppressive Hindu dharma that forced my mother and sister to become sex workers.” It is a bitter irony that devdasi means (woman) slave of god. At this the Tamil writer Bama, who has joined us, interjects: “By calling the children of devdasis children of god, they are implying that brahmins are god!”

I ask Prasad which writers, poets, thinkers, artists besides Ambedkar he likes best. He says he has been inspired by Gautam Buddha, Basava, Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule, Narayana Guru and Periyar. After he graduates he wants to set up a Kannada-language newspaper focused on dalit politics and lives. Prasad’s own poetry, which we discover only later, and only in translation, is wry and beautiful. Fierce. We will share it with you soon.

Aman Kumar

Huchangi Prasad turns up in Delhi horribly under-dressed. He has no socks, and perhaps only one layer of woollens. Vijoo Krishnan, the academic and political activist who has generously agreed to translate for us, takes him to his house so that he can get him ready to face the chilly winds. In between, we sit down with Prasad to have a conversation. And his personality transforms completely. When Prasad is quiet, he is bemused, still trying to soak in the manicured lawns of the India International Centre. When he begins to speak, his eyes brighten with vitality. He is no longer affected by his surroundings. He speaks on what has pre-ordained his life as a child labourer. He speaks on is the old fault line of caste that has been a perennial stain on the shining public image of our nation. For “India Shining” perhaps?

Coming from an average, middle-class, upper caste family, I was, rather unsurprisingly, average, middle-class, upper caste. Caste became a reality for me at 18, when I had to face the reservation system. The first indication of this attitude comes in the hostility to the reservation system — a hostility that has become institutionalised in Kolkata. I am still quite average and middle-class, only much aware of my privilege as an upper-caste research scholar. Upper caste as a marker of identity, as a privilege, first entered my consciousness at 21, when B. R. Ambedkar walked into the Delhi University classroom with copies of “The Annihilation of Caste”. At 23, I meet Huchangi Prasad, also 23. One would expect some more resemblance for two twenty-three-year-olds belonging to the same nation. Our resemblance, unfortunately, ends there — that we are both 23. Unlike him, I was not a child labourer; unlike him, the women in my family were not forced into prostitution; unlike him, I haven’t written a book; unlike him, I have not been attacked for writing a book.

Prasad is a very clear thinker — he is quick to link the devadasi system to the very structure of Hinduism, calling for its annihilation, much like a young Ambedkar. He is careful as a strategist. He understands that the question of dalit assertion in educational institutions is part of a larger, international movement by students, but is careful to make us see each movement in its particularity. We can build alliances, but we have to be careful and see if they are supportive of us, if they have a real interest in our situation, he says.

Listening to him, the sharp divide between the classroom discourse on caste, and the sheer burden of the reality of caste, only became embarrassingly clearer. It is a divide that we can bridge by this very act of staying quiet and listening. But listening to whom? To men and women like Huchangi Prasad, who face caste as a lived experience to be combated, not as another academic discourse to be explained.

Hope comes as a rather pitiful adage in moments of unbelievable distress, and it did not disappoint this time either. Prasad said he wanted to start a newspaper in Kannada once his journalism course in Davenagere University comes to a close in six months. It is in his young hands, in these endeavours where our nation can truly stand.

After his talk to a full house at Ambedkar University, I accompany him back to his room. He wanted to see the India Gate and the Parliament. Our group of five, Indian nationals all, can only see them from the car as the mock drills by the security just before Republic Day could made our sight-seeing very dangerous. Perhaps their fear is correct. For Huchangi Prasad, in this climate of Right-wing opinion, is indeed a very, very dangerous man.

Souradeep Roy

It was a cold, cold, January morning, and exactly a week had passed since the North Indian harvest festival of Lohri, when we sat down by the lawns at the India International Centre, to interview Huchangi Prasad. This is not as strange an introduction as it might sound, and I am rather comfortable rendering it for Prasad, who, last year, after publishing Odala Kichhu, was cornered into a rotting future. A centuries-old state, where his fingers would be broken. A group of drunks carrying the baton of Hindutva gheraoed Prasad, a journalist and writer, one fine day last year, and beat him and threatened to break his fingers if he wrote against Hinduism in the future. He somehow managed to outmanoeuvre the assailants, and escaped.

One is immediately reminded of Perumal Murugan, author of Seasons of the Palm, an evocative novel on dalit life, who was forced to kill the writer in him, earlier last year, for Madhorubhagan (One Part Woman). Just a few days ago, Rohith Vemula, a dalit research scholar, committed suicide.

But Prasad is neither afraid of rotting, nor has his spirit undergone an ounce of shattering, and his fingers, one of them rising with absolute resoluteness were keeping all of us warm on that cold, winter morning. But he was tormented.

I am a twenty-three-year-old student, born into a Brahmin family. Initially, I underestimated Prasad, also 23. A part of my empathy and solidarity for him was merely owing to the fact that everyone, irrespective of our manifold social discrimination, has the right to express themselves. He, however, surprised me not only with the quality of his writing, but his ability to critique Brahminism, and associate intrinsically with the dalit movement. Prasad defied the trinity of race, milieu and moment. Many have reprimanded me for offering judgments from a certain vantage point, for presupposing. I believe another realisation is required if we are to achieve this very distant dream of doing away with the caste system—the realisation that scholarship and intellectuality do not reserve themselves for the highest varna.

Prasad, to my almost barren knowledge of dalit writing, seemed like a young, Kannadiga version of Om Prakash Valmiki, the last part of his name referring to a sage in Hindu mythology. His recollections of his past, done later in the day, were reminiscent of Joothan, Valmiki’s biography. Prasad recited, too, from Odala Kichhu. He seems to have deftly chosen the refrain as his principal poetic device. He recites powerfully, as we later saw, and for all his initial bashfulness, is a very assertive speaker.

But am I saying the goons should leave him alone only because Prasad is good?

It is astonishing that he has been a child labourer, has spent his life in great poverty, and that no one in his family has received education. Unlike many impoverished, labourer children in the country, pushed to dire standards of survival, Huchangi Prasad has been lucky to have access to education. He should be left alone by the wielders of Hindutva, because he is the harbinger of many more of his ilk, of many more Huchangi Prasads.

Prannay Pathak