The Mughal court became a site of cultural production in the early modern world. It was a curious confluence of “Islamicate” and “Indic” cultures. Like any other dynasty with the desire to rule, the Mughals, contrary to the present state-sponsored communal (mis)understanding, did not rupture the existing socio-cultural fabric of the land. Besides introducing Timurid and Mongoloid traditions, they appropriated existing courtly norms and iconographies to legitimise their reign. Take, for instance, the ritual of Jharokha-darshan introduced by Akbar, which stems from the Hindu practice of beholding the deity in the sanctum sanctorum. Another instance of Mughal multiculturalism would be the presence of Jain and Brahmin intellectuals and the production of Sanskrit texts in the court. According to the historian Audrey Truschke, Sanskrit offered the Mughals “a particularly potent way to imagine power and conceptualise themselves as righteous rulers”. The illustrations in a Persian translation of the Ramayana, commissioned by Abdul Rahim Khan-i Khana (completed in 1598 C.E.), now called the Freer Ramayana, depicts the characters of the great epic in settings akin to Fatehpur Sikri. In the same spirit, the Mughals celebrated festivals like Holi and Diwali with pomp and splendour, besides Naurouz and Eid. In fact, Naurouz too is a pre-Islamic festival of Persia, which was retained by the new Islamic rulers after the decline of the Sasanian Empire, with the Arab conquest in 651C.E.

Sparklers in Words: Diwali in Literary Texts

…during the Dewali… the ignorant ones amongst Muslims, particularly the women, perform the ceremonies. They celebrate it like their own Id and send presents to their daughters and sisters…. They colour their pots… fill them with red rice and send them as presents. They attach much important and weight to this season…

These are the words of Sheikh Ahmed Sirhindi (1564-1624C.E.), a Hanafi jurist of the 16th century. This particular tract shows that Diwali was also celebrated by the common Muslim, outside the court. Jean de Thévenot, the French polyglot and traveller who visited India in the 17th century, chronicled the aristocratic celebration of Diwali. “The Gentiles being great lovers at Play of Dice, there is much Gaming, during the five Festival days… a vast deal of Money lost… and many People ruined.” According to historian R. Nath, Abu’l Fazl recorded the unique practice of lighting the aakaash diya, or the lamp of the sky using the Surajkrant, in Ain-e-Akbari:

At noon of the day when the sun entered the 19th degree of Aries, and the heat was the maximum, the (royal) servants exposed a round piece of shining stone (Surajkrant) to the sun’s rays. A piece of cotton was then held near it, which caught fire from the heat. This celestial fire was preserved in a vessel called Agingir (fire-pot) and committed to the care of an officer.

Besides the regular camphor candles (kufuri-shama) on candlesticks of gold and silver to illuminate the palace, the aakaash diya was lit atop a 40 yards high pole, fuelled by maunds of binaula, or cotton-seed oil.

The Divine Light

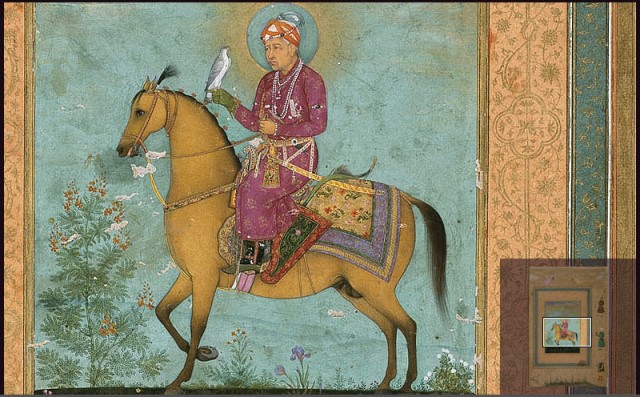

The divine light is an integral part of the Mughal imperial ideology. In paintings depicting the emperor, the halo, borrowed from Christian iconography, surrounded the face of the sovereign from Jahangir’s time. Catherine Asher highlights the importance of the light imagery in Abu’l Fazl’s Akbarnama, in which Akbar is described as an emanation of God’s light. The canopy was believed to set apart the radiance of the legitimate, divinely-guided sovereign from that of the sun. In comparison to erstwhile Islamic rulers, who were called zill-e-ilahi, or the shadow of God on earth, Akbar was loftier — he was also the farr-i-izadi, or the light of God, and thus the perfect man, insaan-i kamil. In paintings, the sovereign’s divine effulgence is shown in contrast to the nefarious darkness of the masses. As John F. Richards points out, the light imagery is traced back to the Timurid-Mongol notions of kingship, in particular, to the myth of Aalnquwa, a Mughal (Mongol) princess “from whose forehead shone the lights of theosophy” (anwar khuda shinasi) and the “divine secrets” (asrar’ ilahi).” Legend has it that she got impregnated by a ray of light while sleeping in her tent, and the triplet born from this divine fertilisation was called nairun, or light-produced. According to Abu’l Fazl, this divine light travelled down from one generation to the next, and was manifested in the persona of Akbar. Though the divine light was not related to Diwali, it shows the imperium’s obsession with the light imagery, as a sacred source of legitimation.

Ignitions in the Gunpowder Empire

Although the Mughal state is no longer seen as a “military patronage state”, gunpowder and the artillery played a significant role in the making of the empire, which has been described as a “patchwork quilt”. Stephen P. Blake writes that Dussehra and Diwali marked the beginning of the campaigning season, and a review of the horses and elephants of the imperial and noble households commenced the celebrations under Akbar and Jahangir. A similar military ritual, symbolic of the ruler’s power, was seen in the Mahanavami celebrations in the Vijayanagara Empire. Perhaps somewhere, there’s a connect between Mughal militarism and the celebration of Diwali. The gunpowder technology was invented in China, and the Mongols used it in warfare. Although Kaushik Roy opines that the Arthashastra bears reference to saltpetre, or agnichurna as the powder that creates fire, the technology got diffused to different parts of Eurasia with Mongol invasions, and the Chagatai Turks brought firearms to India. Tarikh-e-Ferishta, written in between 1606-07 C.E, mentions that the envoy of Hulegu Khan was welcomed with a pyrotechnics display on his arrival in Delhi in 1258 C.E. A blinding display of pyrotechnics or aatish bazi marked the Shab-i Barat and Diwali celebrations in Mughal India. In Calcutta, people still refer to firecrackers as “aatosh-baaji”, a Bengalised version of the original Persian term.

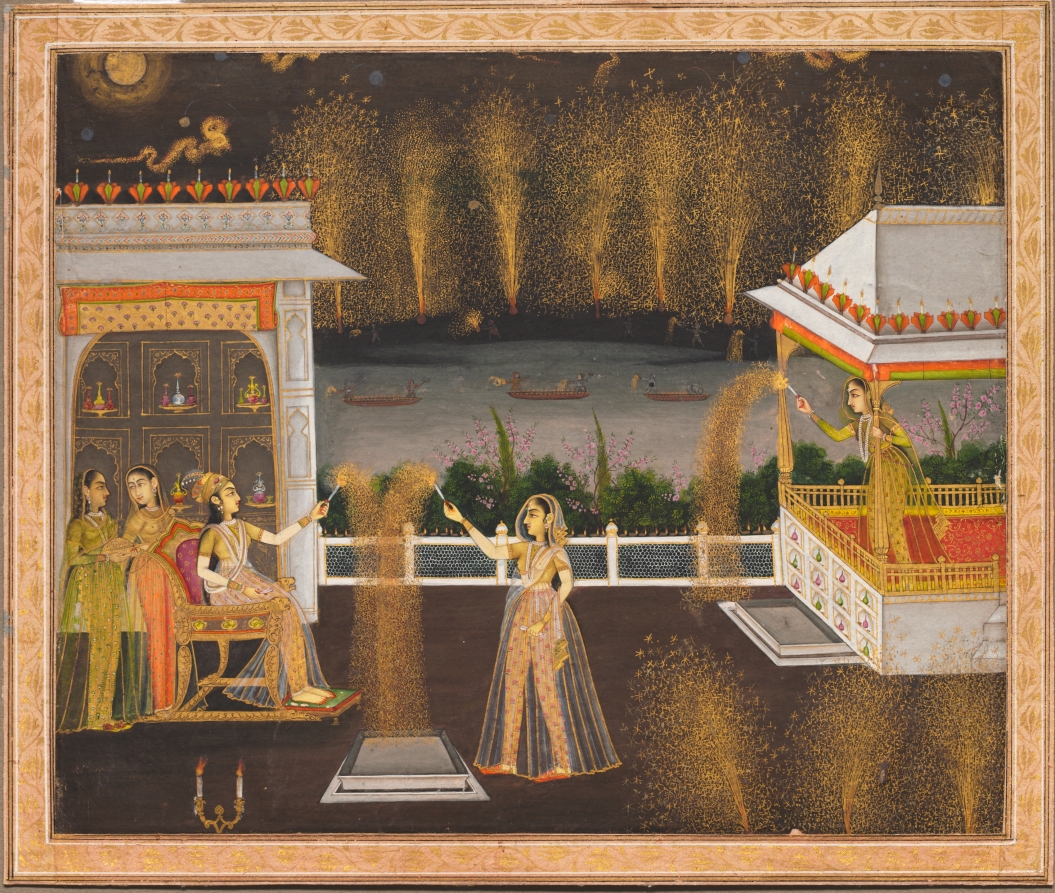

In paintings like The Marriage Procession of Dara Shikoh (circa 1750 C.E.), currently in the National Museum, we see a series of firecrackers dazzling the dark sky. In another painting from the late 18th century by Hashim II, we see court ladies dressed in brocaded fineries, burning sparklers and watching fireworks from a riverside terrace-pavilion, with two gilded candelabra adding to the brightness of the celebration. The celebrations in Shahjahanabad escalated with the coming of Muhammad Shah ‘Rangile’. The gilded Rang-Mahal, with its enamelled and pietra dura artistry, became the venue for Diwali celebrations. His predecessors performed rituals borrowed from the Indic repertoire, like tula-daan or jashn-e-wazan, in which the king was weighed against materials and these materials were distributed amongst the poor. The tradition of chappan thal, which perhaps has its roots in the contemporaneous Krishna Bhakti practices of Braj, became a part of the Mughal cuisine. Sweets like ghevar, peda, jalebi, phirni, kheel and falooda were characteristic of the Diwali air. The Mughal dastarkhwan was laden with the choicest of dishes, just like in Naurouz. The Mughal Diwali or Jashn-e-Charaghan was extensively recorded in court muraqqas under the rule of Rangile. Fanoos or lanterns were released, and chiraghs or lamps illuminated the urban core of Shahjahanabad.

Diwali would begin with a ritual royal bath for which water was brought from seven holy wells, and the emperor was given an aromatic bath while pundits and maulanas chanted sacred hymns. Then the emperor, dressed in soft muslin, would visit the harem to meet his wives and concubines. In the court, his courtiers, according to their status in the administrative hierarchy, were supposed to present a symbolic tribute to the emperor, called nazrana. Though the celebrations suffered a setback during Nadir Shah’s invasion in 1739 C.E., the celebrations continued till the reign of Bahadur Shah ‘Zafar’, notwithstanding the acute financial constraint and the shrinking resources of the empire. With the emergence of the regional or provincial Mughal courts, such as those in Awadh and Murshidabad, in the 18th century, Jashn-e Charaghan became an integral part of these courts as well, in the wee days of colonialism. With the aroma of honey and almond wafting through the heavy air of decadence, the kufuri-shama casting silhouettes of a glorious past, and Nazeer Akbarabadi’s nazms resonating with a sense of coexistence, the last Mughal Diwalis were a curious confluence of tears and laughter.