My first encounter with the magical absurdity of Naiyer Masood started when I was doing my masters in Urdu literature from Mumbai University. During a lecture, our fiction teacher said, if literature has no meaning, it cannot be called literature. Immediately, I asked her who her favourite writer was. She replied Naiyer Masud. I said I find no meaning in his stories. My teacher smiled in confusion since there was no answer.

I had first read Naiyer Masud a month ago, beginning with his collection of short stories Seemiya, (Metamorphosis or The Art of illusion). My first response was confusion: I soon realised that there is no meaning in his stories. I could not sum up what these stories stood for. Despite the confusion aroused by the absurdity of the text, I felt that this meaninglessness had a colourful spell as well. Any reader of Masud will feel a vague tranquility which is beyond words. The magic of the absurd lured me into booking train tickets to Lucknow.

On October 21, 1995, I was at his doorstep along with a poet friend Qamar Siddiqui, now a lecturer at Mumbai University. At the main entrance of Adabistan – his old style bungalow residence – a boy stopped us. He was probably his son. I told him that we had come from Mumbai to meet Masud sahib. Few minutes later, a slim and tall man in his late fifties welcomed us with a generous smile on his face. That day was one of the most memorable days of my life. He had shown us volumes of dastaan and tazkira (description of poets and literati of the past) written and published a century ago, which he had probably inherited from his father, Syed Masud Hasan Rizvi “Adeeb”, also a well-known scholar of dastaan.

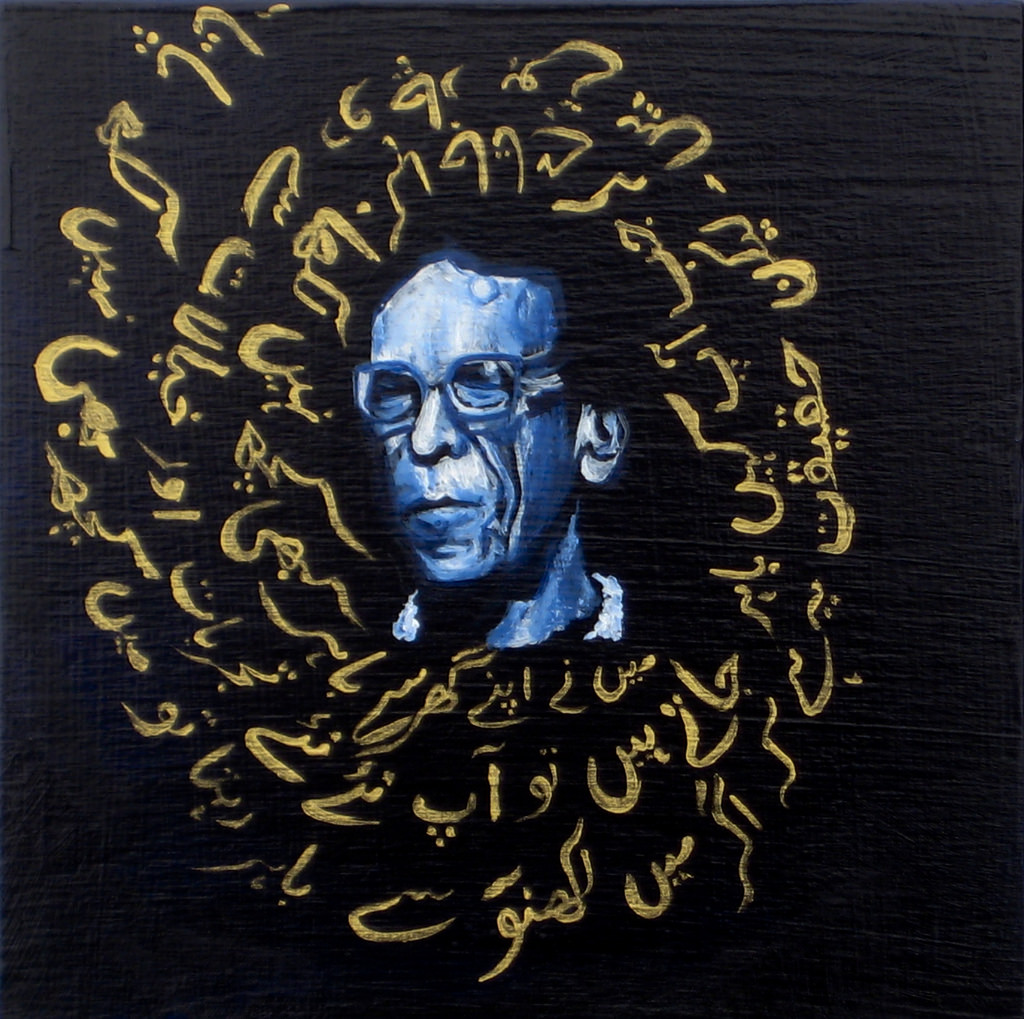

I can still clearly remember the moment when I asked Naiyer Masud about the enigmatic and absurd structure of his stories. He smiled and said, “Meaning in a story is like the scales of an onion. You keep peeling them one after another, but in the end, there is nothing. This nothing is the meaning.” We had not completely understood what he was saying, but he had a seductive way of explaining. He told us about many mysteries of the world, of cultures and of countries. He said that there are so many things in this world which was beyond comprehension.

We listened to his enigmatic stories, clicked pictures with him till late evening. He autographed Itr-e-Kafur (Essence of Camphor), his second book, and gifted it to us.

I went to Lucknow to meet him for the second time in the summer of 1998. He was very fond of knowing what young writers were reading, and discussed the books he was reading at length. In this meeting, he talked about Stephen Hawking’s concept of time, and explained how time was metamorphosed into dastaan and other old stories. I told him that I had started writing short stories. He wanted to read. I was very pleased. That day he also spoke about scientists who claimed that there was evidence of mysterious sound recordings from outer space. He repeated what he had told me the first time I met him: that the universe is a puzzle.

Six months later, I sent him my first story “Gabu Ki Bakri” (The Goat of Gabu). After a couple of weeks, I received his letter. He had liked my story and suggested it should be published in Shabkhoon, a literary magazine edited by Shamsur Rahmam Farooqi – one of the best Urdu critics. Most of Masud’s stories had been published in Shabkhoon. A few months later, my story found a home in the same place.

In the next three or four years, my love for Naiyer Masud turned into detachment. I was in the company of Mumbai’s Progressive Writers, under the shadow of Sajid Rashid, Salam Bin Razzak and others. I was told that Naiyer Masud was part of Farooqi’s agenda to foster modernism. Their movement was conspired to attack the progressive movement, and to deflect the influence of Premchand, Manto, Bedi and Chughtai. I was in a dilemma. I was not in favour of literature as a meaningless activity that was devoid of any concern for humanity. In spite of that, I was still under the magic spell of Masud’s absurd stories.

This dilemma continued for a decade. Meanwhile, Masud’s third and fourth short story collections, Taus Chaman Ki Mayan and Ganjefa were published. I had stopped writing short stories by then, and had published two novels. He had read my first novel Nakhlitan Ki Talash (in Search of an Oasis) and had written a letter to me. He advised me to continue writing. Skills grow with the passage of time, he said. Now when I look at the books published over the past few years, I find Ganjefa to be, without a doubt, one of the finest collections of short story after Manto and Chughtai. Here, Masud evolved absurdity into a great history of Lucknow with people, things, animals, rivers, old beds, buildings, bazaars, toys, clothes, mirrors, utensils, birds. Dreams were strewn within dreams in such a way that these objects became living beings who were eager to tell their stories. In these stories, there was an immense sense of decay, dejection, deprivation, and faded memories.

This style of story-telling is derived from the idea that narrating a story is like peeling the scales of an onion. It is as if the onion is life itself, and the act of peeling the narration of life. Ganjefa shows that Naiyer Masud was concerned about humanity in a larger sense. He was not a propagandist like the other progressives. He was a collector of memories, dreams, and all other mysterious of the past.

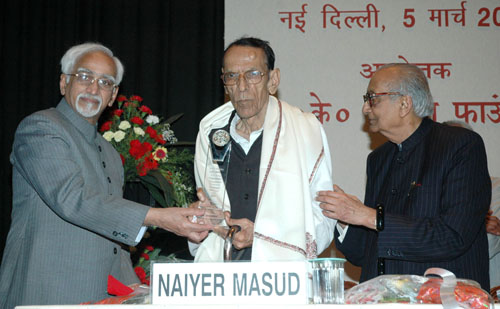

His perception of the short story is unmatched in the history of Urdu fiction. The simplicity of his style casts a charm which makes illusion magically absurd and alluring. When I started writing my fourth novel, Rohzin, I too tried to find my craft in the debris of memories, dreams, mysteries, and things which had passed in front of my eyes. Gopichand Narang, the former President of Sahitya Academy, had once said that though the Urdu modernist movement was astray, Naiyer Masud was different. Indeed, Naiyar sahib was unique and there are so many things one can learn from this uniqueness.