Brahma Prakash is a writer, cultural theorist and Assistant Professor of Theatre and Performance Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. His previous book, Cultural Labour: Conceptualising the ‘Folk Performance’ in India (Oxford University Press, 2019), is credited with changing how we see folk performances and cultural practices in India.

The writer and cultural theorist talks in his recent book about curtailment and resistance in contemporary India but with lots of hope. He talks about the artists and writers’ need to reinvent language and hopes for emancipatory politics and culture. He asks for solidarity, which, according to him, is not a privilege but an urge that we have to come with even if we differ radically.

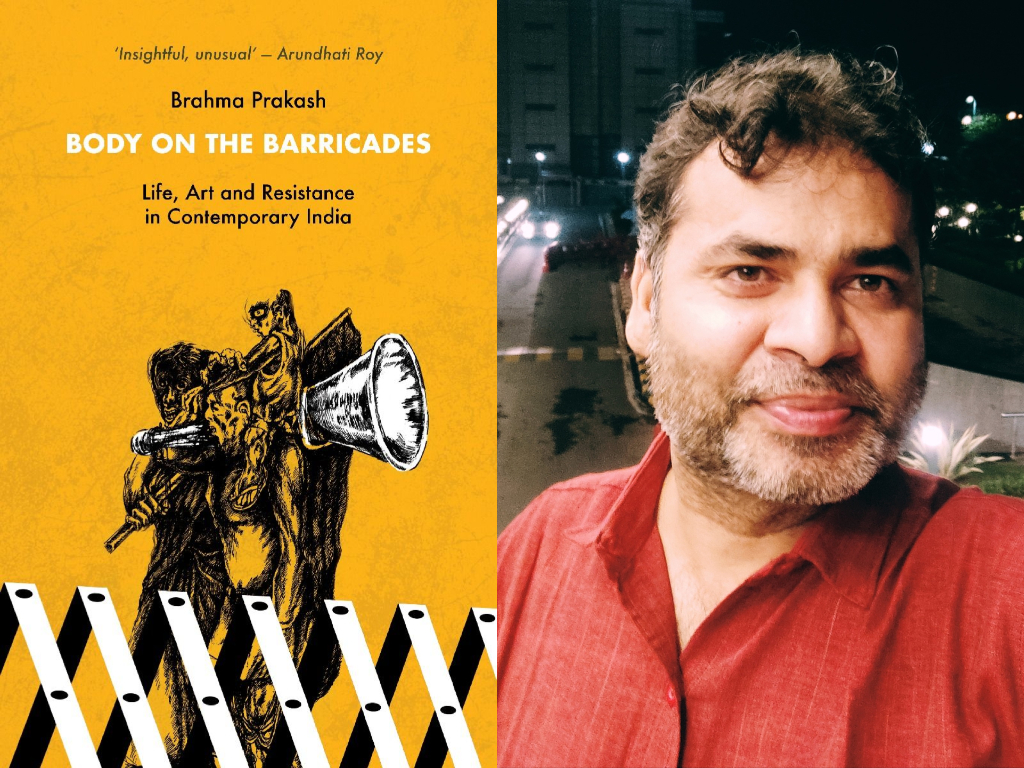

Within months of its publication, Brahma Prakash’s Body on the Barricades (Leftword Books, 2023) was recognised for its distinct style of writing style and a book of hope amidst curtailment by scholars and critics. From personal memory, anecdotes, songs, poetry, theatre, anthropology, philosophy, and cultural and political theories, the book draws on various sources without claiming disciplinary boundaries.

The writings almost resemble lyrical essays propounded by the writers like Maggie Nelson, Claudia Rankine, and others. The book offers an unusual gaze into life, art and resistance in contemporary India through a metaphor of body on the barricades — how one excavates hope when one is pushed to the limit in the situation of breathlessness. Through a wide canvas of contemporary events unfolding in the background of the COVID-19 pandemic, the book creates an extreme metaphor of a body on the barricades to navigate into the pandemic-like situation that characterises contemporary Indian society at large. While the body takes the central stage in any pushed situation, a barricade symbolises curtailment and resistance. In this situation, the barricade symbolises excessive policing and the weapons in the hands of precarious workers to defend their rights and freedom.

The book also reflects upon marginalised identities and the conflicting narratives of such identities with the State that unfold almost like horror stories. It has poignantly captured bodily acts like breathing, mourning, dancing, singing, and other creative expression as an act of resistance. The book has lucid language, yet it is written with a sense of authenticity that dares to speak out. The book ends with a clarion call for hope amidst the despair surrounding us. The author writes in first person, second person and third person yet ensures that every narrator who has been pushed to the boundaries gets enough space to speak out about their acts of resistance rather than being a passive dead protagonist lying on the barricade.

K Kalyani (KK): What motivated you to write this book? Can you briefly talk about how did it start? Also, if you can reflect upon the title of your book and its noticeable unusual writing style.

Brahma Prakash (BP): Let me say that more than any motivation, it was provocation and incitement that made me write this book. This book was not planned. It just happened. It started as a response to the situations and events that unfolded in the forms of the Rohith Vemula protest, the migrant crisis, the anti-CAA and the farmers’ protest and other COVID-related crises. The book was a gutsy response to a gutsy politics that was (and is) unfolding before us. Like many of us, I was feeling suffocated. I wanted to breathe. I wanted to say something. Writing became an act of breathing for me. Like many other writers, I felt that epic tragedies must have epic responses.

But the journey was also very personal. I would write songs and plays for the groups. While I was doing my academic work, I was feeling a sense of loss — unable to connect with a larger section. Then, I started writing columns for various media platforms. The immediacy of the writing and response again connected me to the street theatres. Positive feedback from readers and wider dissemination of some of the pieces motivated me to take on this mode of writing.

More than anything else, for me, this book is my experiment with writing. Like many of us who have come from marginalised backgrounds, I, too, struggle a lot with writing. I was not familiar with accepted grammar and phrases, which also helped me to develop my own style. I was also trying to find my voice, my associations, and my disparate experiences in writing.

At a point in time, writing for me becomes a search for self and method. This personalised mode of writing makes me cry. It gives me strength. Sometimes, I embody words; sometimes, I get carried by them. The lyrical mode has been so liberating for me. Why do I write, how do I write, and for whom do I write? The questions of language and accessibility of writing are very political questions. Scholars like me who came with reservation and affirmative action cannot evade this question.

Because of its uncanny writing style, not many publishers were ready to take on this project. I must say that Indian publishers remain very conservative when it comes to experimenting with writing. The lyric essay does something to your writing. Like poetry, it gives us a force. I am also interested in the very force of the writing. I also believe that some kinds of thinking only happen in poetry and lyrics. I do not think the Bhakti and Sufi could have emerged in analytical language.

It was the fore of poetry and music that gave a real depth to their philosophy. It is about passionate writing; it is about breathless writing; it is about writing while gasping; it is about writing while walking. A discussant in Patna made a very pertinent remark by saying that kitab aise likhi gayi hai jaise lekhak hanf raha hai (The book is written in a way as though the writer is gasping).

The title had its own journey; the initial title was When We Can’t Breath: Curtailment of Life and Freedom in Contemporary India. Then, I also realised that I am not only talking about curtailment, but I am also talking about hope and resistance. Body on the Barricades indicates the extreme situation, yet it also indicates the last resort from where we can retreat to life. To resist, we need to have hope; to transform, we need to have hope. As a scholar, an activist, a writer, and a critic, I think we need to keep reinventing hopes in difficult times. We can only count on our radical hopes.

KK: Your previous book, Cultural Labour: Conceptualising the Folk Performances in India (2019), was an in-depth study of performance practices of marginalised communities. In a way, the book seems to shift the gaze from a performative lens to the lens of resistance. Can you reflect more on how do you look at resisting bodies? Do you think it is in any way resisting bodies that are performative?

BP: Thanks for pushing me to bring both of my works together. I can see an interaction happening between both of my works. In my book Cultural Labour, I analyse theatre and performance as empirical categories, if not always anthropological. In the second book, curtailment and protest themselves are becoming performative; movements are acquiring theatricality, and bodies are appearing in gestures.

Also, in terms of method, theatre is becoming a topography of thinking as well as a gaze that articulates the bodies. We can see the gestural formation of political theatre in protest and assembly. While scholars have examined the elements of performatives in many recent protests, I would like to claim that there has been a performative turn of the political itself — from the way protestors marched together to the ways slogans have acquired gestural significance and musical presence. In this regard, Jacques Ranciere would say that ‘politics does have a structure of theatre in which political actors do assume different roles’.

In the earlier understanding or in the case of Augusto Boal’s forum theatre, the political theatre would often claim that it is a rehearsal for revolution. But in recent years, we have seen how protesters are using the elements of theatre to make their protests more effective and corporeal. More theatres are happening on the barricades; more singers are coming to the protest sites.

While resisting bodies do not necessarily have to be performative, what we are witnessing is the various ways resisting bodies are deploying the performative language or appearing through performance. Resisting bodies can be anti-performative and take a clear anti-performance stance where performance becomes the logic of the capital and the name of merit in a caste society.

Whether it was the student protests after the institutional murder of Rohith Vemula or the anti-CAA or farmers’ protest, the nature and languages of protests have changed. The protest is becoming more musical, it is becoming more performative, it is becoming more bodily. It is becoming more festive. In this context, I compare migrant labour with the figure of a dancer.

KK: Your book has an interesting canvas to look at. You have navigated from issues in Kashmir to COVID-19 to Hathras. Amidst your discussion, it is interesting to read that there is a performative way in which each of these narratives unfold. The narratives themselves become part of political and cultural rethinking. Are you also trying to rethink performance by going beyond its conventional spatiality and temporality?

BP: Yes, to an extent, but these experiments are not new. There are theatre scholars and practitioners who have been engaged in this mode of thinking. Antonio Artaud compared theatre with the plague. In this case, theatre becomes a topography of thinking and plague becomes a site of theatre. As performance remains at the core of both neoliberalism and Brahminism, I am also trying to make the connection obvious by expanding the meaning of performativity by creating some rejoinders in Indian and South Asian Contexts.

KK: Why do you think the idea of the Body is central to the book? Can you explain how you connect the idea of the Body with different themes in your book?

BP: In her reading of this book, Prof. Nivedita Menon has pointed out this connection more clearly — how the power of emotions sets this body, these bodies in motion — rage, grief, solidarity, love, hatred. In different ways, the body comes to the centre when we are pushed. Second, in general, unless it does not come to our body, we don’t feel the pain, or we perhaps don’t resist in the same way. In all these pushed situations, the body becomes the centre. In the urgency of life, the body takes all the attention. All the chapters in the book mobilised the bodies to make this point of curtailment, resistance, and hope.

KK: What interested me most while reading your book was the engagement with the idea of Barricade. It is, of course, more than just a physical barrier. There have been histories of Revolution and Barricade. Within the context of India, the image of Barricade has been both containment and suppression. Can you tell us more about how you investigate the histories of barricading and the ideas of barricading that are embedded in your book?

BP: Yes, in the Indian context, we find more negative references to barricades, but barricades also have a glorious history that we should not forget. Also, if you are thinking about the displacement drive against the Adivasis communities or the recent bulldozing of the houses of minority communities, many times, those communities have been erecting barricades using their own bodies. But as I have discussed in the book, the barricade now has become an instrument in the hands of authorities. It has also happened because the physiognomy of the city has changed. I think the point is beautifully elaborated in the book on Barricades by Eric Hazan.

KK: In your Chapter “The Trial of Art,” you have interestingly discussed how an artist is suppressed within the State and is assigned derogatory sobriquets like terrorists, suspects, etc. Why do you think contemporary State art has become a conflicted category? Can you also discuss how the bodies of the artist, the imagery of the barricade and the resistance come together?

BP: I have discussed the relationship between the state and the art in a more idealised situation. I draw from Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong, who sees this relationship antagonistically. For a state to remain as a state, it must maintain law and boundaries; art to remain as art has to break the law and boundaries necessarily. The power of art lies in its refusal. The contradiction is the fundamental of their constitution. Taking the real incident of poet Varavara Rao, I have used the poet’s metaphor in an ambulance. The poet here is not about Varavara Rao or any individual. The poet represents our sensibility. Thus, the question we can ask is, what does it mean for a society where their poets are in an ambulance or in a coma?