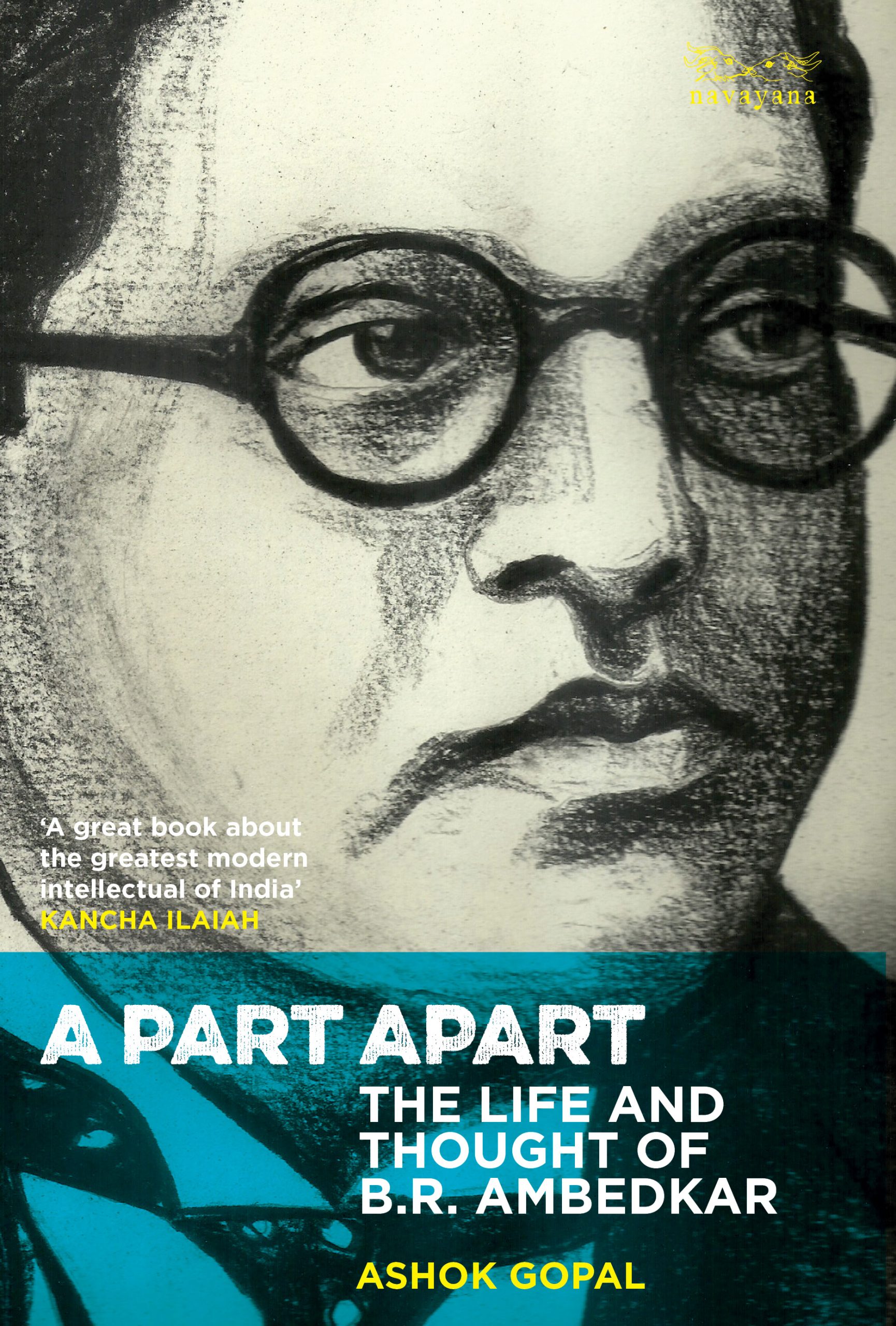

A Part Apart: The Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar by Ashok Gopal (Navayana, 2023) is primarily about the influences on first law minister and constitution writer Ambedkar. Gopal, who graduated in history and has researched his subject for nearly a decade, extensively cites from what Ambedkar wrote and read; and new and existing sources in English and Marathi. He traces Ambedkar’s transformation from a somewhat superstitious boy to a mature politician whose struggles pitted him against some of India’s most powerful forces throughout his life.

[On 20 March 1927, B.R. Ambedkar and his followers from the Bahishkrut Hitakarini Sabha, acting on the Bole Resolution that allowed for equal access of all public property to all citizens, went up to the Chavdar Tank in Mahad, Maharashtra, and consumed its water. The Tank had been off-limits to Untouchables according to local tradition, which they defied, setting up equality as the norm. The following excerpt from Ashok Gopal’s magisterial biography, A Part Apart: The Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar, details prominent reactions to that event and the attacks on its participants.

Apart from Gandhi, who wrote in his periodical Young India, the periodical Bhaala, or Spear, edited by a ‘virulently orthodox Brahmin’ follower of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, also responded to the events at Mahad. Ambedkar took on the latter in his weekly tabloid, Bahishkrut Bharat. The following is an extract from the sixth chapter of the book, ‘Making History’.]

Groups of Caste Hindus, armed with sticks and stones, had gathered at the town’s main squares, and some had stormed into the mandap, erected near the venue of the conference, for serving food to the participants. The Caste Hindus threw away the cooked food and beat up around twenty Untouchables who had sat down to have lunch. In all, sixty to seventy persons, including three or four women, were attacked. Among those who were severely injured were four Chambhars, P.N. Rajbhoj, Bhanudas Kamble, Kamble’s wife and their child. The demonstration of ‘Shudra mentality’ by the Caste Hindus of Mahad greatly angered the Untouchables, but Ambedkar and a CKP [Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu, a caste group in Maharashtra] resident of the town, one Potnis, urged the Untouchables to stay calm, Dnyanprakash reported.

***

Several periodicals carried reports about what had happened at the first Mahad conference. Dnyanprakash, Navakal and Vijayi Maratha—a Non-Brahmin periodical—provided eyewitness accounts matching the report in Bahishkrut Bharat. The Times of India published a brief report on 24 March 1927. In response to the last item, which did not give a correct account of what happened, ‘a special representative’ of The Bombay Chronicle provided a statement, which was published in the inside pages of the newspaper on 25 March as a lengthy, single-column item (“Kolaba Depressed Class Conference”). The ‘special representative’ was most likely Ambedkar or one of his Savarna aides, as the report matched what was published in Bahishkrut Bharat, with one major addition: The Muslims of Mahad had shown ‘much sympathy’ for the Untouchables and saved many of them from the attacks of Caste Hindus. On 29 March 1927, The Bombay Chronicle carried a letter by ‘Human Rights’—also likely to be Ambedkar or one of his aides—who pointed out that among the assaulters in Mahad were some persons who were ‘usually clad in immaculate khadi’. This showed that the ‘lip homage which the Mahatma receives from the orthodox Hindus is nothing but the worship of his personality and has precious little to do with the doctrines preached by him’.

Over a month after the violence, Gandhi’s periodical, Young India, published a report on it sent by one of the Savarnas who attended the conference, Tuljaram Mithaseth (Biwalkar & Kamble, 2015). Beneath the report, Gandhi wrote: ‘Assuming … that the incident is correctly reported, there can be no question about the unprovoked lawlessness on the part of the so-called higher classes.’ Every Hindu who considered the removal of untouchability to be of ‘paramount importance’ ought to ‘publicly defend the suppressed classes on such occasions’, he wrote. But, following the line adopted by the Congress in 1923, he left it to the Hindu Mahasabha and like-minded organisations to ‘condemn the action’ of the Caste Hindus.

Ambedkar followed the media coverage closely and responded to it in Bahishkrut Bharat. The primary target of his rejoinders was one ‘Bhaalakar’ Bhopatkar, an admirer of Tilak and a virulently orthodox Brahmin editor from Pune. In his periodical Bhaala (Spear), Bhopatkar had written that the incidents at Mahad had been caused by overenthusiastic social reformers who did not realise that untouchability could not be removed overnight. The issue had to be tackled in ‘slow steps’ without hurting the feelings of Caste Hindus. Writing in the first issue of Bahishkrut Bharat, Ambedkar asked Bhopatkar, ‘Why don’t you follow the same approach when demanding Swarajya? The crux of the matter was that the Caste Hindus didn’t deserve Swarajya—they wanted Swarajya only for themselves; they were unwilling to accept the citizenship rights of the ‘minority’ of Untouchables. It was only because the district collector at Mahad was a European, the police inspector was a Muslim, and Muslims of the town had sheltered the Untouchables that the latter did not suffer the ‘atrocities’ that would have been committed under a ‘Hindu raj’, Ambedkar wrote.

Bhopatkar had also said that Caste Hindus would ‘break the backs’ of Untouchables if they tried to disturb the traditional social order. Ambedkar hit back:

The bahishkrut varg is not made of dung or wax. It has shown valour on the battlefield. And we know well how people like Bhaalakar get scared when they face Muslims or Europeans. And should there be an occasion when people try to break our backs, we will not hesitate to break their heads.

Bhopatkar then changed his tune. In the 1 April 1927 issue of Bhaala, he said that many of those who had walked up to the Chavdar Tank would have begged for leftover food the previous day. Such people who voluntarily accepted leftovers—which was ‘suitable for animals’—were not worthy of being called Touchables, he declared. Ambedkar countered: Untouchables like Mahars did not beg for food. They demanded it as a right, as a part of their balut. Moreover, if eating leftover food was considered the key criterion for determining who was an Untouchable, then many Maratha women working as maidservants in Brahmin homes, Brahmin students who demanded food as madhukari (alms for Brahmins), and all Brahmin women who finished the food left by their husbands ought to also be considered Untouchables. Bhopatkar’s inability to see the flaw in his argument revealed the hallmark of ‘Brahmin justice’. It twisted arguments and rules to ensure that, whatever happened, Brahmins retained their supreme position. Bhopatkar continued his attack in Bhaala on 25 April 1927, but Ambedkar ignored it. Turning Bhopatkar’s notion of pollution on its head, he said he saw no point in ‘polluting’ his mouth by tasting Bhopatkar’s rubbish.

In the course of this nasty exchange, Ambedkar touched upon one crucial point: his stand on Untouchables’ entry into temples. The account in Bahishkrut Bharat as well as the reactions of reformist Hindus like Gandhi had suggested that the violence in Mahad was unjustified because the rumour about them planning to enter the Vireshwar Temple was false. That left a key question hanging: Did the Untouchables want to enter the temple? Ambedkar gave a categorical answer as part of his response to Bhopatkar on 3 April 1927.

We want equal rights in society, and we are going to acquire these rights by remaining within the fold of Hindu society as far as possible, and, if necessary, by kicking away the Hindutva that has been adjudged to be worthless. Needless to say, if we wholly leave Hindutva, we will not be interested in going to temples.

As we will see, Ambedkar had spoken about the possibility of leaving the Hindu religion in his speech delivered at Nipani in 1925, but on that occasion, he had not explicitly spoken about rights. His statement in Bahishkrut Bharat in April 1927 made it clear that, as far as he was concerned, the fundamental issue was about rights that were denied to Untouchables and not about allegiance to the Hindu religion. At the same time, he linked the denial of rights to a Hindu identity. If the change desired by the Untouchables did not occur, they would become non-Hindus.

Ambedkar’s use of ‘Hindutva’ requires a clarification. The term had gained prominence and a distinctive meaning after V.D. Savarkar used it as the keystone of his vision of a Hindu rashtra (nation), elaborated in a booklet published in 1923, Essentials of Hindutva. In his formulation, the term was the marker of a religio-ethnic identity determining citizenship. Apart from Hindus, non-Hindus could be citizens of Savarkar’s Hindu rashtra if they considered it to be the land in which their ancestors had lived, and it was the land in which their religion had originated. Ambedkar’s use of the term did not refer to Savarkar’s citizenship qualifications. He added ‘tva’ to ‘Hindu’ only as a suffix to form an abstract noun—the state of being Hindu.