“The gutter was about 20 feet deep. First Paresh went in. He pulled out two or three buckets of waste; then he came up, sat for a while and went in again. He screamed as soon as he went in…

“We didn’t know what had happened, so Galsing Bhai went in. But there was silence. So, Anip Bhai went in next. And yet, none of the three now inside made a sound. So, they tied a rope around me and sent me in. I was made to hold someone’s hand; I am not sure whose hand it was. But once I grasped it, they tried pulling me up and that is when I became unconscious,” Bhavesh speaks without pausing for breath.

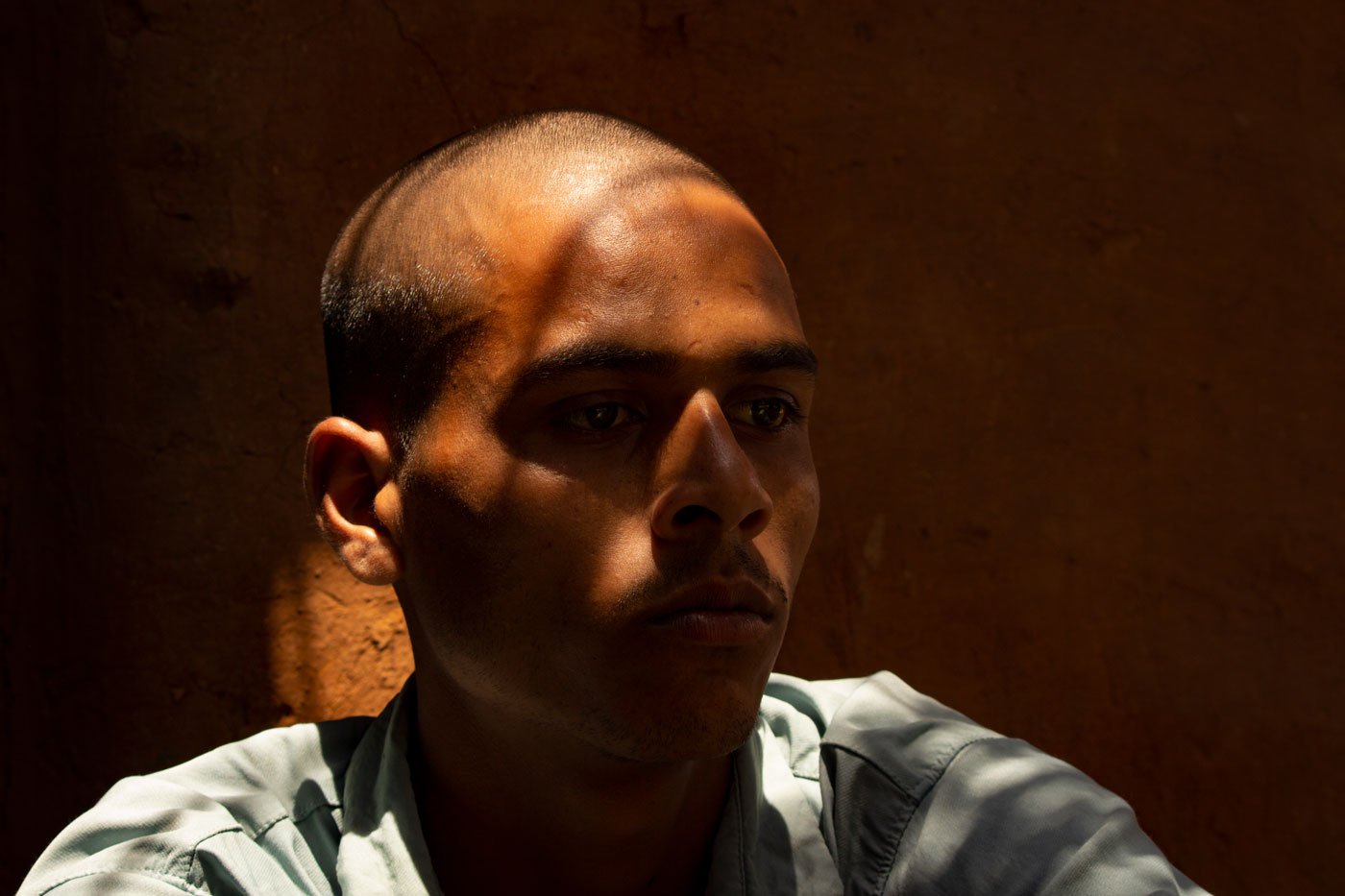

When we met Bhavesh, it had been less than a week since he lost his brother Paresh in front of his eyes, along with two other workers. He is visibly in pain, recalling the details of that tragedy. And speaks in a voice distinctly sad and depressed.

Bhavesh Katara, 20, from Kharsana village in Gujarat’s Dahod district is a ‘lucky’ survivor. He was one of only two who made it out alive in a disaster while five men – all Adivasis – were cleaning a toxic sewer chamber in the Dahej gram panchayat in Bharuch district. The other survivor is Jignesh Parmar, 18, from Balendiya-Pethapur also in Dahod.

Working with them were Anip Parmar, 20, from the same village as Jignesh; Galsing Muniya, 25, from Dantgadh-Chakaliya in Dahod; and Paresh Katara, 24, was of course from the same village as his brother Bhavesh. These three died of asphyxiation in the sewer. [The ages cited here are taken from their Aadhaar cards and have to be treated as uncertain approximations. Those are often arbitrarily assigned by impatient low-level officials].

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki/People’s Archive of Rural India

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki/People’s Archive of Rural India.

But what were five Adivasi men from villages around 325 to 330 kilometres away doing, cleaning sewers in Dahej? Of them, two were apparently working on monthly payments in another gram panchayat, while the rest – their families really do not know much about the range of odd jobs they were doing to scrape by. They are all from very marginalised sections of the Bhil Adivasi group.

Disaster struck on April 4, 2023. “One person was inside,” recalls Jignesh, who was working in the adjoining chamber that day. “He had inhaled toxic gas and was helpless. When another one [Galsing] went in to save that guy, the gas hit him too. He fell inside. To save them both, Anip went in, but the vapours were too strong. He felt giddy and collapsed.

“We kept shouting to save him,” says Jignesh. “That is when the villagers came. They called the police and the fire brigade. When Bhavesh was sent in, he too fell unconscious because of the gas. When they were pulled out, they took Bhavesh to the police station first. Once he became conscious, the police took him to the hospital.”

Why did they wait for him to get conscious to take him to the hospital? Neither of them has an answer. Bhavesh, though, was saved.

*****

Anip had been working in Dahej even before he got married. His wife Ramila Ben joined him there immediately after their wedding in 2019. “I used to go [to work] early, by eight in the morning,” she says. “He would go alone at 11 in the morning after his lunch, and do whatever work the talati saheb or sarpanch would ask him to do,” Ramila Ben says, explaining why she was not around at the time Anip died.

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki/People’s Archive of Rural India.

Image Courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

“Earlier we used to clean gutters together,” she says. “We did gutter-work for four months after my marriage. Then they asked us to do ‘tractor work.’ We would go around the village with the tractor and people would put their garbage in the trolley. I would separate the waste. In Dahej, we have cleaned big gutters also. Do you know those private ones with huge chambers? I used to tie a rope to a bucket and pull the waste out,” she explains.

“They used to give 400 rupees for each day you worked,” Ramila Ben says. “I also got 400 rupees on those days I went. After about four months, they started paying us monthly. First nine thousand, then twelve, then finally fifteen thousand rupees.” Anip and Galsing were working on a monthly payment basis for the Dahej gram panchayat for a few years. They were also given a room to stay in by the panchayat.

Was there any written contract they signed before they were employed?

Their relatives are unsure. None of them can say whether the workers who died were hired by private contractors roped in by the civic bodies. Nor do they know if they were in contractual, arrangement with the panchayat – either temporary or permanent.

“There must have been something on paper with a letterhead but that must be in Anip’s pocket,” says his father Jhalu Bhai. And what about Bhavesh and Jignesh, the two surviving workers, relatively new on the job? “There was no signing or letter involved. We were called and we went,” Bhavesh says.

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

Bhavesh had been working there for ten days when the tragedy struck. Jignesh and Paresh were called to work on that day. It was their very first day of work. And none of their family members had any idea about the nature of the labour they were to undertake.

Paresh’s mother, 51-year-old Sapna Ben, is in tears as she speaks: “Paresh left the house saying there is some work in the panchayat, and they are calling him there [to Dahej]. His brother [Bhavesh] was already there ten days earlier. Galsing Bhai had called him. You get 500 rupees a day is what both Bhavesh and Paresh had said. Neither of them told us that they were to clean sewers. How did we know how many days they would take? How did we know what work they would do there?” she asks.

In Galsing Muniya’s house, 26-year-old Kanita Ben had no idea either, about her husband’s work. “I do not get out of the house,” she says. “He used to say, ‘I am going to work at the panchayat’ and leave. He never told me what he used to do. It must have been seven years that he was doing this work. Never did he talk to me about it, not even when he returned home,” she says.

Not a single member in the five families had any idea about the work their sons, husbands, brothers, or nephews were doing, except that it was with the panchayat. Jhalu Bhai found out only after Anip’s death what it was his son had been doing. He feels their dire need for money drove them to such work. “Pansayatnu kom etle bhoond uthavavnu keh to bhood uthavavu paday . [Panchayat work means we have to lift a pig’s carcass if that is what they ask us to do],” says Jhalu Bhai. “If they ask us to clean the gutter, we must clean it. Or they won’t let us stay in the job. They will say go home..”

Did the ones who died, or those who went newly to this work, know what it involved? Bhavesh and Jignesh say they did know. Bhavesh says, “Galsing Bhai told me they will give you 500 rupees a day. There will be some gutter cleaning, he had said.” Jignesh confirms this, adding that “Anip called me. I went, and they got me to work straightaway in the morning.”

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

None of the workers, bar Jignesh, had studied beyond middle school. Jignesh is in the first year of his BA in Gujarati programme – as an external student. But the reality they all faced was that, often, getting inside the gutters was the only way for most of them to get out of poverty. There were stomachs to be fed and children to be educated at home.

*****

According to the 2022-23 annual report of The National Commission for Safai Karamcharis (NCSK), 153 people have died in Gujarat while engaged in the hazardous cleaning of sewers between 1993 and 2022. That is the second highest number of deaths after Tamil Nadu which logged 220 in the same period.

However, authentic data on the actual number of deaths, or even the number of people employed in cleaning septic tanks and sewers, continues to be elusive. The Gujarat Social Justice and Empowerment Minister informed the state legislature that a total of 11 sanitation workers died between 2021 and 2023 – seven between January 2021 and January 2022. And four more between January 2022 and January 2023.

The total number would rise if we added the reported deaths of eight sanitation workers in the state over the last two months. That would include two in Rajkot in March, three in April in Dahej (reported in this story). And another two in in Dholka and one in Tharad in the same month.

Did they have any safety gear?

The FIR filed by Anip’s 21-year-old wife Ramila Ben at the Bharuch police station holds the answer: “Sarpanch Jaideepsingh Rana and the deputy sarpanch’s husband Mahesh Bhai Gohil were aware that if my husband and the others with him… were to get inside a 20-foot deep foul-smelling sewer without any safety mechanisms, they could die. And yet they were not provided with any safety gear.” [The deputy sarpanch is a woman. And as often happens in conservative societies, it was her husband who really exercised power in her name].

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

The cleaning of sewers and septic tanks by humans stands banned ever since The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers And Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013 extended the earlier Employment Of Manual Scavengers and Construction Of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993 . All this, however, seems to exist only in theory. For the same law speaks of people in “hazardous cleaning,” and their right to protective gear. Where the employer does not fulfil his obligation to provide such gear and other cleaning devices to ensure the safety of the worker, that becomes a non-bailable offence according to the law.

The police, acting on Ramila Ben’s FIR, arrested the sarpanch of Dahej gram panchayat and the husband of the deputy sarpanch, both of whom quickly applied for bail. The families of the deceased know nothing about the outcome of their application.

*****

“ Agal paachal koi nath. Aa panch sokra se. koi nath pal pos karnara mare ,” emotions choke Kanita Ben, Galsing’s wife. (“I have no one left. These five children are there. He used to take care of our food, of the kids’ education. Now there is no one to do that”). After her husband’s death, she stays with her in-laws and five daughters; the oldest Kinal is 9 and the youngest Sara is hardly a year old. “I had four sons,” says Galsing’s 54-year-old mother Babudi Ben, “Two are in Surat. They never visit us. The older one stays separately. Why would he feed us? We used to stay with Galsing, our youngest. Now he is gone. Now who is there for us?” she asks.

Ramila Ben, widowed at 21 and with a baby in her womb, is equally lost. “How do I live now? Who will take care of our food? There are people in the family but for how long can we depend on them?” She is referring to her five brothers-in-law, a sister-in-law, and Anip’s parents.

“Now what do I do with this child? Who will take care of us? Where do I, this lone woman, go in Gujarat?” She is from Rajasthan but cannot go back. “My father is too old to do anything. He cannot even farm. There is hardly any land, and my family is big. I have four brothers and six sisters. How do I go back to my parents?” Her eyes are fixed on her stomach as she speaks. She is in the sixth month of her pregnancy.

“Anip used to bring me books,” his ten-year-old sister Jagruti begins telling us. But her voice is soon drowned in sobs.

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

Image courtesy Umesh Solanki / People’s Archive of Rural India.

Bhavesh and Paresh had lost their father when they were very young. Three other brothers, two sisters-in-law, a mother and a young sister make the family. “Paresh used to pamper me,” says his sister Bhavna, 16. “My brother used to tell me that he would let me go on my own to study if I passed Class 12. He had also said that he would buy me a phone.” She has appeared for her Class 12 board exams this year.

The families of Galsing, Paresh and Anip appear to have received Rs. 10 lakhs in compensation from the state government. But these are large families with many members – that have just lost vital breadwinners. What’s more, the cheques would certainly have come in the names of the widows – but the women knew nothing about the arrival of the money. Only the men did.

How come a community of Adivasis, a people living in close proximity to nature ended up doing this work? Did they not have any land? No other livelihood opportunities?

“In our families we own small patches of land,” explains Anip’s Mota Bapa (older paternal uncle). “In my family we may have 10 acres of land but then there will be 300 people feeding off it. How can you manage? You have to go look for work as a labourer. Our land may give us enough to survive, but nothing to sell.”

Do they not invite stigma by doing such jobs?

“There was no stigma really,” says Paresh’s Mota Bapa, Bachubhai Katara. “But now that something like this has happened, we feel that we should not do such dirty work.

“But how to survive…?”

This story was originally written in Gujarati by the author and translated into English by Pratishtha Pandya.