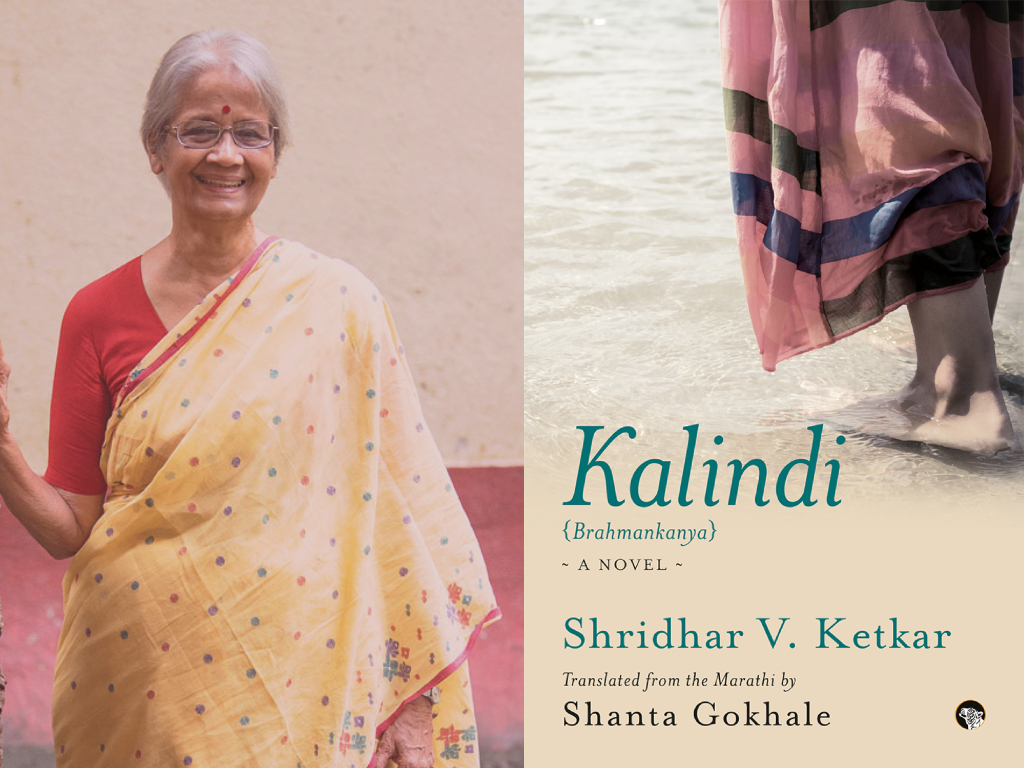

Shridhar V Ketkar’s Kalindi (Speaking Tiger, 2022), translated from Marathi by Shanta Gokhale, originally published as Brahmankanya in 1930, has been hailed as brave and ahead of its time. It brings the classic alive for the contemporary reader, and we see how relevant it remains almost a century later.

It is the early 1900s in Mumbai. Educated and financially independent, Kalindi Dagge dreams of living in a casteless and equitable society as a single mother—a life far removed from the one she had in the stifling world she left behind. A world where she was the daughter of a brahmin lawyer, Appasaheb Dagge, and the casteless Shanta; and the granddaughter of another brahmin and his schoolteacher mistress who rejected the idea of marriage.

In her conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, Shanta Gokhale talks about translating Ketkar’s novel, women’s rights and more.

Githa Hariharan (GH): Brahmankanya was first published in 1930. The challenge the text presents to the contemporary reader is constructing a context by peeling off one layer after another: that this is a novel of ideas by a sociologist; that its time is the earlier half of the 20th century, with nationalism driving debates on Hindu reform; that a man takes up the issue of women’s education and marriage choices; a man born a Chitapavan brahmin takes up caste inequalities, but with an awareness of class contradictions and transactions. Suppose we begin with the most important layer, that of caste. Would you comment on the continuity and/ or change of caste discrimination between Ketkar’s time and ours?

Shanta Gokhale (SG): For me, Brahmankanya is, first and foremost, a story, told in a direct narrative style, with snappy dialogue, great attention to characterisation and to the contemporary circumstances that trap its characters, drawn from a wide cross-section of society, ranging from outcasts to upper castes, from educated young women to merchants to members of minorities to leaders of workers’ unions. Each of these characters pushes the boundaries of custom, tradition and religion to find a modicum of personal freedom to be who they are. The reader is engaged throughout in following the detailed unfolding of their trajectories, wondering how they will resolve their several problems. The greatness of the novel lies in the sociological concerns of the author not being allowed, for the most part, to turn a story into a thesis. Its flesh-and-blood characters and their journeys make up the vehicle Ketkar has fashioned to carry his preoccupation with caste which, he believes, has done untold harm to Indian society and will, if not fought, do even more harm to the country as a nation. Caste is not merely a layer in this story. It is the driving theme.

Caste, it must be remembered, had been part of the political discourse in Maharashtra since the mid-19th century, well before Ketkar reached adulthood. In the second half of the century, when the movement for the country’s independence was gathering force, the sharpest debates had taken place between two passionate nationalists, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopal Ganesh Agarkar. Born within a few days of each other, these two towering personalities had been fellow students and friends at school, and colleagues at Fergusson College in Pune, before they fell out over their opposing approaches to the country’s independence. Tilak contended that independence had to be won first before social problems were addressed. Agarkar took the longer view, arguing that social reforms were of prime importance if the Hindu was to become a fit citizen of a confident, modern, independent nation. Caste and women’s education were the main axes on which these debates revolved.

Ketkar was a vital link in the history of this discourse. With sociology as his discipline, he had an academic interest in the problem of caste. At Cornell University where he had done his graduate and post-graduate degrees, he had become acutely aware of the flaws in the western understanding of caste. He was equally conscious of the flaws in the conservative Hindu view of caste. His choice of subject for his doctoral thesis was aimed at addressing both. In the introduction to his thesis, published as a book in 1909, titled The History of Caste and Race in India, he says he had researched the subject of caste with the hope that, deeply complex as the subject was, a knowledge of its history might help people see that the system was by no means rigid. It had undergone great changes since the Vedic age when the four varnas had been laid down as the organisational principle of society. He took the Manav Dharmashastra, popularly known as Manu Smriti, written between 200 BCE and 200 CE, as the chief evidence of change when the four varnas had multiplied into dozens of jatis. Ketkar’s argument was that change was inevitable. It had to happen. But he confessed to not being sure how it could be brought about. “To effect change in a society so complex and so highly organised, a tremendous force is needed, and where is it?” The upper castes, he asserted, had no interest in changing a system which worked so well for them. And so, “When individuals cannot remove an evil, it is the duty of the community or government to do it.” Neither having done their duty, he relies on the knowledge of history to disabuse people of the notion that caste is divinely ordained and cannot be tampered with. Fully conscious of the apparent impossibility of the task, he says, “All attempts made by previous workers to break caste have failed, but it should not be thought that all possible remedies have been exhausted… It is a critical moment, a question of life and death and there is no way to escape.”

Ketkar’s conviction, shared by his contemporary Jotiba Phule, that the government had a role to play in correcting the injustices of the caste system, was to become reality when the country became independent. Has that made the difference Ketkar and Phule had hoped for? Legally, yes. On the ground, no. In fact, what government intervention seems to have done is to make individual action redundant. In the public mind the problem of caste discrimination has been taken care of. Where is caste these days, people blithely ask. And yet news comes in every day of the worst caste atrocities happening across the country. We still have thriving caste organisations with their annual get-togethers and caste-driven projects. People still marry within their caste, even sub-caste. Honour killings happen when these lines are transgressed. While the upper castes eat together, there is still very little socialising between the upper and lower castes. Roti-beti transactions thus remain more or less where they were in Ketkar’s time. Ketkar’s hope that change will happen has been so far belied. But in his time, Ketkar still hoped and still pushed. The existence of caste was, as he said, a cancer that had to be removed. Knowing that The History of Race and Caste in India was likely to have been read only by fellow scholars, Ketkar was evidently compelled to address the problem in another, more accessible form. Brahmankanya was the result.

Also Read : Shanta Gokhale’s translation of Smritichitre

GH: There is also the complex situation of a person born into an upper caste talking about possible solutions to caste inequality. Would you help us contextualise this ‘reformist’ intention and consequent plan for action in Ketkar’s times, especially in the context of nationalism?

SG: Ketkar’s argument in Brahmankanya is precisely that if anyone can change caste hierarchies as the organising principle of society, it is brahmins, the original authors and highest beneficiaries of the system. Only brahmins have the social power to stand up against the system which their ancient forefathers instituted.

There was no concerted plan of action in Ketkar’s times. The big initiatives were the Prarthana and Arya Samaj. These are examined in the novel as pushbacks against the system. Then there is the fictional Vaijnath Shastri (he could be Ketkar himself) who attempts to write a Smriti to rival the Manu Smriti, but dies before he can complete it. The protagonists of the novel arrive, heuristically, at the realisation that an all-inclusive movement for dismantling the caste system must be left to the future. Meanwhile such difference to the status quo as could be made in Ketkar’s time could only come from individual action. The novel begins with an individual action — an inter-caste, inter-class marriage — which has been taken in the naïve hope that it would serve as an example that such a thing was possible. The fact that what he had hoped for did not happen comes as a shock to the idealist. He and his children now begin to explore possibilities that go beyond individual action. None of them answer the need that they feel for change. With this knowledge gained, they return to individual action. This is not a case of returning to where they began. This is not a circle but the first curve of a spiral. The individual choices they make which go against social norms are now made in the full knowledge that they will have little or no effect on society in general rather than on the naïve hope on which the initial action was based. The hope is that more such individual actions might, in the long run, dent social norms. In that sense, there is progress.

GH: Ketkar’s novel has been hailed as a classic that is ahead of its times. Yes, the discussion of a more equitable society, in terms of caste or gender, is brave; Ketkar takes risks, as do his characters. But is it not very much of his times, rather than ‘ahead’? Is it not a part of the debate on women’s rights in general, and women’s education in particular, that was going on in the larger movement for Hindu reform at the time?

SG: In one sense Brahmankanya is of its times. But in another very important sense, it can be said to be ahead of its times. The novel is of its times because reformist movements which addressed a range of social issues including caste and women’s education were part of the public discourse that held centre stage. However, while the discourse was dominated by the educated and the articulate who wielded powerful pens and were entitled to public fora, there was a massive undertow of orthodox belief opposed to change, that surged up at critical times. We have seen its resurgence in our times. Tilak was of his times, and continues to be of our times. He is revered in Maharashtra even today. Agarkar has been totally forgotten. Ketkar himself was not a popular novelist of his times because he swam against the stream. He was also a victim of the orthodoxy in his personal life — he suffered because he chose to marry a German Jew, deemed mlechcha or vratya by the orthodox citizens of Pune. His family severed all ties with him.

The orthodox undertow came into its own when the British government in India did what it did not generally do: it intervened in Hindu social customs through acts like the Hindu Widows Remarriage Act of 1856 and the Age of Consent Act of 1891, which raised the age of consent for sexual intercourse for all girls, married or unmarried, from ten to twelve years. Reformists who supported the new laws were ostracised and excommunicated. Many of them have recorded the terrible effects this had on their social and economic lives. Who then was of the times? The orthodoxy, not reformists.

GH: Ketkar seems to question the value of individual non-conformist action — that of the brahmin who marries, on principle, a woman from a lower caste, for instance. There is also the question about the motivation of individual reformers — we would call them activists — as well as the question of how they are to lead middle class lives if they work for the well-being of the working class. Does the search for balance seem rather strained in the debate about activism, on the individual level, as well as at the organisational level?

SG: Ketkar does not question the value of individual non-conformist action. He only re-evaluates it. His protagonist never once regrets his action. He merely reviews it from a realistic perspective, regrets his failure to see reality, a fact that caused his estrangement from his children, but still asserts the correctness of his action when he invites his children back into the home, blesses the non-conformist choices they have made and looks forward to bringing them into the discussion about caste.

The only character in the novel who fits the description of an activist working for the well-being of the working class while leading a ‘middle-class’ life is the trade unionist Ramrao. He neither shows nor expresses any sense of strain between his professional and private life. In fact, he is the most clear-headed and balanced character in the novel.

Watch | Shanta Gokhale reads from Shivaji Park: Dadar 28: History, Places, People

GH: As a translator, I think of you finding a link with the authorial voice. You said, for instance, apropos your translation of Lakshmibai Tilak’s Smritichitre, that you found an affinity between her ‘homely’ language and your own. What was the relationship you established with the text Brahmankanya; its authorial worldview; and its narrative style?

SG: I read Brahmankanya first in the late sixties. I felt impelled to read it again a decade or so later. What first drew me to the novel was the easy, natural friendship between Kalindi, the chief protagonist, and Esther her Bene Israel friend. This was a breath of fresh air in a literary world which stuck closemindedly to the Hindu middle class. A very close friend of mine had been Bene Israel, a community that found no representation in Marathi fiction. Then suddenly I discovered Esther.

In my second reading of the novel, I was taken with Ketkar’s direct narrative style, the freedom with which he had coined new words that had become current in the spoken language of my times. To my great relief, his language was free of the punditry of Sanskritised Marathi as well as the sloppy vagueness of sentimental expression that had come to dominate fiction of the fifties and early sixties. Although Ketkar’s knowledge of Sanskrit was apparent through some of his coinages, it was seamlessly melded with a modern language that had its roots in a sensibility moulded by European thought. Most importantly, Brahmankanya unlocked the world of the textile mills and the relationship between owners and workers. Although the textile worker lived in a large swathe of the city I inhabited, he was once again absent from Marathi literature. The only exception was dramatist B.V. Warerkar’s novel published in the same year as Brahmankanya — Warerkar’s novel centred on the relationship between mill-owners and mill workers. The novel was not much read then, and has been forgotten since. But Warerkar later wrote a play based on the novel which did well precisely because it did not confront reality with the toughness of Ketkar’s novel, and submitted to audience taste in the naïve sentimentality of its denouement.

After my first novel Rita Welinkar was published, a couple of critics observed that it carried shades of Brahmankanya. I had not realised it, but once it was pointed out, I saw how true the observation was and how deeply I had responded to Ketkar’s novel.

Read an extract from Kalindi here.