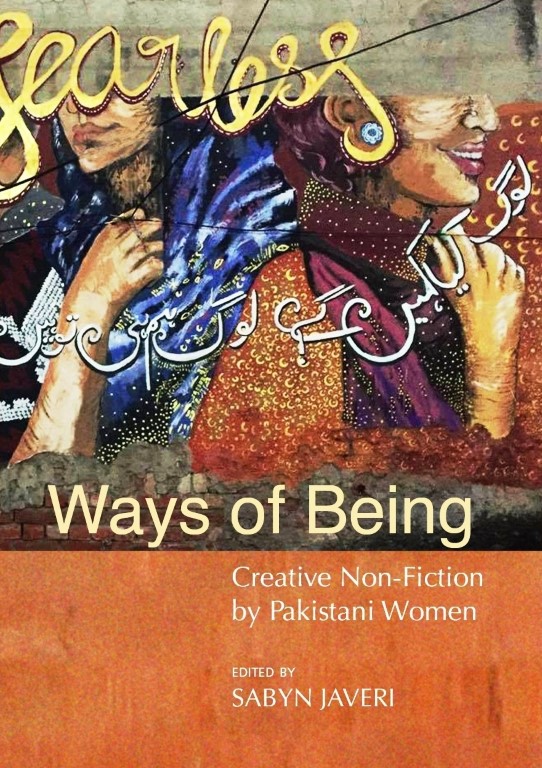

Edited by Sabyn Javeri , Ways of Being, (Women Unlimited, 2022) is a rich and fascinating collection of reflections, reminiscences, musings—and excellent writing features from fifteen of the most articulate and creative non-fiction writers from Pakistan.

Large-scale migration and transnational mobility have rendered national borders porous, while the Internet has internationalised communication in a way that practically erases territorial boundaries. Questions about ‘being’ and ‘belonging’ acquire an urgency that demands articulation: how does a writer relate to her context, whether at ‘home’ or ‘away’, and locate herself and her writing in it? For the purposes of this anthology, Javeri believes that, “A Pakistani writer is one who feels a connection to the land either by origin or by sensibility.”

The following is an excerpt from the book.

As Wide As Love

I first spoke to Sabeen Mahmud in December 2007, after a friend put us in touch. The friend told me about T2F, a café and public space in Karachi created by Sabeen to nurture and promote cultural dialogue.

…

T2F kept swelling in popularity. I’ve never known a space in Pakistan to be so inclusive of class, gender, sexuality, religion, ethnicity, and cultural scope. Sabeen organised book launches in Urdu and English, western and eastern musical evenings, tabla classes, film screenings, and talks on current affairs, politics, science, philosophy, literature, and more. The café included a gallery, a discount bookshop (with books in Urdu and English), and a little stall selling mugs, posters, CDs, among other things. Everyone was welcome. No boundaries. T2F defined spaciousness because its maker, Sabeen, was the definition of spaciousness. Her spirit was, to borrow an idiom from Colum McCann, “as wide as love”.

The words are taken from McCann’s short story, “Everything in this Country Must”, and its title comes from this moment “…I was shivering and wet and cold and scared, because Stevie and the draft horse were going to die, since everything in this country must.”

Pakistanis are familiar with the lament. We are shown, daily, that everything must die—everything good and meaningful, that is. What is brutal and deadening must never die.

Sabeen was shot dead on the night of Friday, April 24, 2015, after leaving an event she organised at T2F, titled “Unsilencing Balochistan—Take 2”. The speakers were a group of Baloch activists, among them Mama Qadeer, a leader of the Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, and Farzana Majeed Baloch. Both have lost loved ones.

Mama Qadeer’s son, Jalil, went missing in 2009 and his tortured corpse was eventually found in 2011. In an interview with the journalist and author, Mohammed Hanif, Mama Qadeer lists the injuries on his son’s body “without betraying emotion, as if remembering his son’s collection of books”. But even more gut-wrenching is when Mama Qadeer decides to take his four-year-old grandson, who was born with a hole in his heart, to see his father’s mutilated corpse. His reason:

I didn’t want him to grow up with the regret that I didn’t let him see his father one last time. So I took him and showed him his father’s body and told him everything. One of Jalil’s eyes was badly damaged and my grandson asked me who had done that to Daddy. I said Pakistani agencies. And then he asked me who were Pakistani agencies. And I told him that, too.

The other speaker on that ill-fated night of April 24 was Farzana Majeed, whose brother has been missing since 2009. Since then, she has set up protest camps, first all over Balochistan and then in Karachi, attended court hearings, and led protest rallies. She tells Hanif, “International media came. TV cameras came. But they didn’t really do much. Nothing changed.”

Why are they missing? Why doesn’t anyone want to hear about it?

The answer rests in the decades-long battle for an independent Balochistan, the largest and poorest province in Pakistan. Its literacy rate is the lowest in the country. Its representation in the armed forces, negligible; in industry and commerce, even less. Yet, it has the greatest wealth of natural resources in the country. The federal government earns billions, annually, from its gas fields, while Balochistan receives a pittance. The construction of the Chinese-run Gwadar Port in south Balochistan and the displacement of Baloch from their land—which China uses as a naval base—has only added to the conflict. If the province sees itself not as a part of Pakistan but as its colony, it is with reason.

Before Farzana Majeed’s brother disappeared, he was a student of English at Balochistan University, the same university where Farzana did her masters in biochemistry. He was in an organisation committed to raising awareness of Baloch rights. A number of the organisation’s leaders have gone missing. Mama Qadeer’s son was also involved in politics. He was the information secretary of the Baloch Republican Party and a campaigner for Missing Persons. Before his disappearance and subsequent death, his friends had warned him that he would be next. It didn’t stop him.

When on April 24, Sabeen Mahmud organised “Unsilencing Balochistan—Take 2”, she knew she was taking a risk. The event was meant to be held at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), but was called off. Sabeen opened a space for dialogue with Baloch activists when everyone else backed away. She had apparently received a bullet in a letter a few days earlier but she stayed true to her belief that, “Fear is just a line in your head. You can choose which side of the line you want to be on.”

Her mother, who was also shot and in critical condition but did recover, reported that two gunmen followed them on a motorcycle after they left the event. Five bullets entered Sabeen, who died before reaching the hospital. She was thirty-nine years old. The gunmen have still not been identified. Many people argue that the murder may not be linked to the last event she was ever to host, but the chronology is impossible to ignore.

There was a continuous outpouring of grief for Sabeen in the media. People reminded themselves to keep her legacy alive, to never give in to fear and censorship. Her death cannot mean the end of the dream she made real: an inclusive public space where it is possible to evolve—regardless of your background and beliefs, or whom you know or don’t know. Like Sabeen, each of us must choose which side of the line of fear to live on. But at what cost? Her death comes on the heels of so many deaths for Pakistan it is hard to know which ones to name first. Must we learn to list them as stoically as Mama Qadeer listed the torture wounds on his son’s corpse? Either that, or an anger impossible to bear.

But among the things Sabeen had no patience for was self-pity. One of her Instagram photos was of a protest banner held against the religious cleric, Abdul Aziz. The banner read: “Do not pity the dead, pity the living, and those who live without love.”

Sabeen lived the way she wanted, true to her immense vision for justice and freedom.

And she will always be loved.