Palestinian lawyer and writer Raja Shehadeh is the founder of the human rights organization Al-Haq, an affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists. In addition to writing on the law, he has written several books including Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape for which he was awarded the Orwell Prize in 2008; Strangers in the House, When the Birds Stopped Singing: Life in Ramallah Under Siege, and Where the Line in Drawn: Crossing Boundaries in Occupied Palestine. His highly acclaimed work combines sharp commentary on the Israeli occupation of Palestine with poignant insight into a people’s loss of home, and their daily experience of discrimination, violence and apartheid policies in their own land.

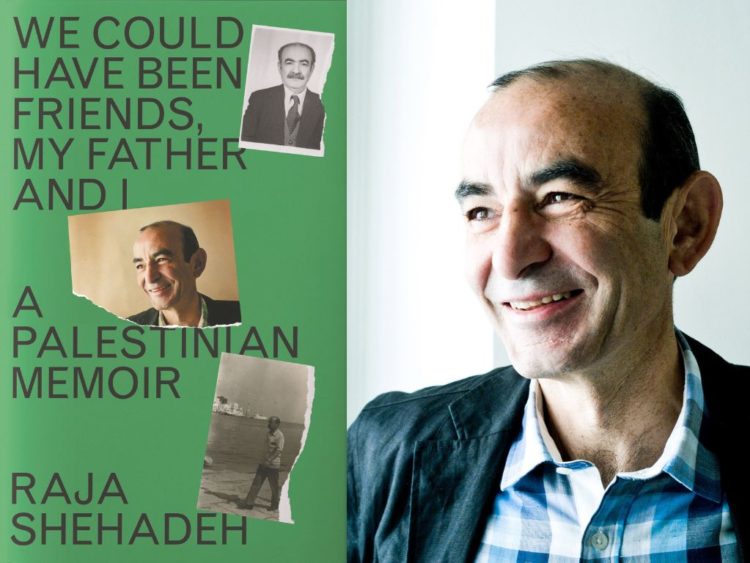

In his new book We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir (Profile Books, 2022), Shehadeh once again brings together personal and political histories. He probes, with great sensitivity, his relationship with his father – a relationship necessarily recalled in the context of the struggle for human rights in Occupied Palestine.

Shehadeh’s father, Aziz Shehadeh, was a lawyer and an activist and a political detainee. He was vocal about his resistance to the British mandatory period, then under Jordan, and, finally, under Israel. As a young man, Raja fails to recognise his father’s courage and, in turn, his father does not appreciate Raja’s own efforts in campaigning for Palestinian human rights. When Aziz is murdered in 1985, it changes Raja irrevocably. In We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, this father-son relationship frames the tragic complexities of Palestinian occupation, as well as the necessary struggle for hope.

In this conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, Raja Shehadeh speaks of the parallels between his father’s life and activism and his own. He also asserts the importance of never giving up on hope, or the continuing struggle for Palestinian rights. At the heart of justice for Palestine is , he says, recognition and acknowledgement of the Nakba – the ‘catastrophe’ in 1948 when Palestinians were forced out of their homeland.

Githa Hariharan (GH): Throughout the book, we get a sense of viewing a legacy. There is the obvious aspect of the father-son relationship: the values your father passes on to you, of hard work or determination, for instance. There are also the disconnects and the could-have-beens, signposted by the title, We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I. But let me enlarge the question since the legacy is a far more complex one. As in the book, we could peel off layer by layer of this legacy. To begin with, the ‘innocence’ that both your father and you exhibit, at different points of time, that the rule of law will survive, in some form. Then, finding at every turn that this is not true, the struggle for hope.

Raja Shehadeh (RS): It was the convergence of a number of emotions and incidents, more than a desire to highlight my father’s legacy, that provided the impetus to write this book.

I had lately been convinced that the recognition of the Palestinian right of return is crucial to forge any sort of peace between Israelis and Palestinians. I wanted to highlight this in my writing but was not sure how to go about it.

It happened that a friend brought me a copy of the telephone directory of Jaffa/Tel Aviv from the period of the British Mandate over Palestine. There I found the names of my maternal grandfather Judge Salim Shehadeh, and Aziz Shehadeh, my father. I looked at that piece of ordinary document and thought, My parents and grandparents were living in Jaffa. It was a real place and all that life is now denied. I knew then that I should write about it – to evoke that life. Around the same time, another friend who worked at the British Museum in London bought a booklet from a nearby bookstore written by my father in 1936 entitled “The ABC of the Arab Case in Palestine” When I read it, I was struck by how lucid and well argued it was. That was only the tip of the iceberg. But it gave me an incentive to delve into my father’s papers – piles I had stacked in a cabinet in my office without ever reading them.

In these papers, I discovered a treasure trove of information about the cases my father had worked on during his long career as a lawyer and activist – information I realized was not known by the public. Among the files was one on his ceaseless attempt at pursuing the case of the return of the Palestinian refugees to their former homes in what became Israel after 1948. I began writing that story. Yet it had to be preceded by a full description of my parents’ life in the Jaffa they knew, and from where they were forced out by the Jewish Army in April 1948. Only in this way would the measure of the tragedy be appreciated by the reader.

Overshadowing the telling of this and other tales was another which I tried to explore throughout the book: why was it that when my father endured banishment from Jordan, or imprisonment, or disappointment at many points of his life, I had remained distant and never tried to get closer to him and ask him to describe his experiences to me? The source and cause of that tension between us became an important theme in the book which ended up as a love letter to my father.

GH: Would you say the larger legacy of occupation and resistance is marked by change as well as continuity from your father’s time to yours?

RS: It was only through writing We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I and the exercise of my imagination in the course of writing the various sections of the book that I came to realize the close similarity between my father’s experience and mine. I had not been aware of this earlier. Writing about how he experienced the take-over by Jordan of the West Bank that had been part of Mandate Palestine, and the changes that ensued in the landscape and life of the place, made me realize that it was not unlike my experience of watching the transformation of the West Bank into Israel after the 1967 war through building Jewish settlements with all that this entailed. I also realized that just as he could not believe that they will not be returning to their former homes in Palestine, I couldn’t believe that Israel will succeed in transforming our territory and achieving its de facto annexation to Israel. And just as he had put all his energy at using the law to resist these measures, so had I.

Read an extract from We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I

GH: If we describe much of the earlier struggle, though brave, as ‘failed action’, would you comment on the value of this history to strengthen struggle for freedom and justice in our own times?

RS: It could be said that we’ve both failed in achieving our immediate goal: my father of the return of the refugees and mine in stopping the construction of more settlements. And yet the important matter is that we did not leave it to happen without a serious struggle. Documenting my father’s struggle was what I tried to do in the book. I was always struck by the wisdom of Krishna’s advice to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita that “You have a right to your actions, / But never to your actions’ fruits. /Act for the action’s sake. /And do not be attached to inaction.” That might have been the driving force behind my father’s activities and mine. It is important for those struggling now against forces that might seem formidable to remember this and never to give up. Others will come and build on previous struggles until the goal is achieved. Giving up on freedom and justice is giving up on what makes us human.

GH: A rather large question pretending to be simple: what is your idea of ‘freedom and justice for Palestine’?

RS: In the case of Palestine, recognition of the Nakba is at the heart of freedom and justice for Palestine. A well-known Israeli writer has written that Israel’s success in the 1948 war was no less than a miracle. It was no such thing. The disparity in the means available to the Jewish army and to Arab forces made it certain that the Jewish army would win. The real miracle was Israel’s success in denying that a Palestinian nation lived in Palestine which they succeeded in obliterating almost entirely. After seventy-five years, and with the wealth of photographic evidence and innumerous memoirs of Palestinians, they continue to get away with it. They continue to deny the Palestinian Nakba.

GH: Your book resonates powerfully in the present. You write of two generations of Palestinian lawyers struggling against the Nakba and its ongoing manifestations. Reading this text as the Netanyahu government attempts to bring in judicial ‘reform’ alerts us to how dire the situation is, not just in terms of the ‘rule of law’, but of the idea of law itself, of legal policy; of justice, in fact.

RS: The protesters against the right-wing settler government in Israel headed by Netanyahu fail to realize that violations and threat to the rule of law would not begin with the measures the Israeli government is proposing to initiate. They have been going on for over four decades when the Jewish settlers, assisted by the Israeli army, committed atrocities against the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories – taking over their land and violating their rights, as well as attacking their person and properties. Despite extensive reporting, the law enforcement authorities in Israel refused to investigate these violations and take action against the perpetrators. The shameful practices against Palestinians infected Israel’s political system and will continue doing more harm under the present right-wing government.

I end my book by mentioning what my father believed and repeatedly advocated: The only real victory is when we’ve both won.