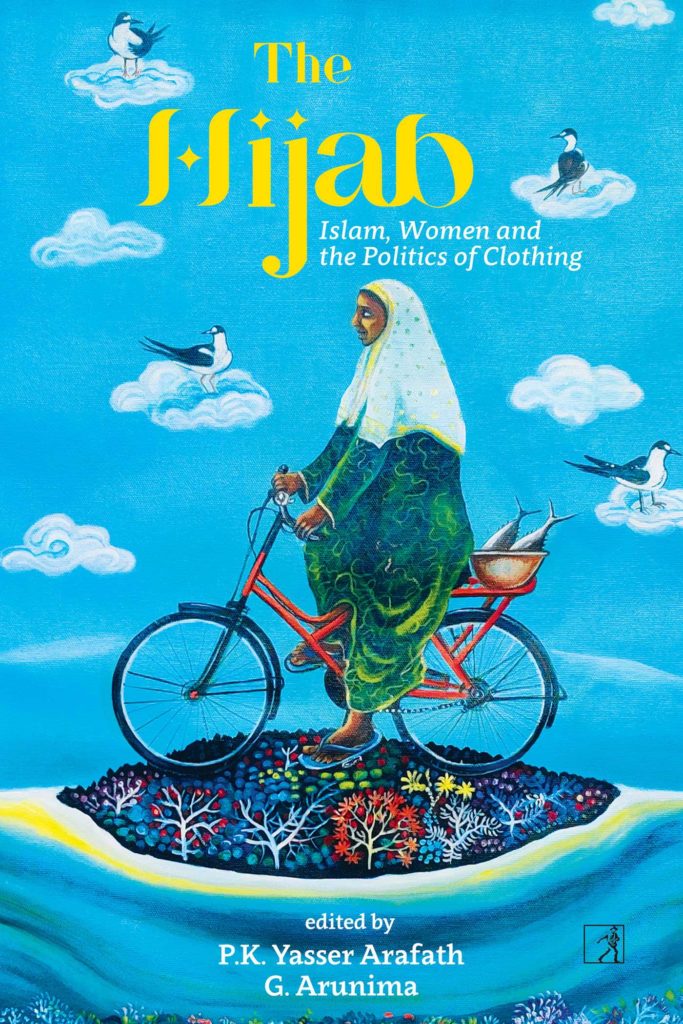

The Hijab: Islam, Women and the Politics of Clothing (Simon & Schuster, 2022), edited by P.K. Yasser Arafath & G. Arunima is a collection of essays, primarily from India but also with a couple from Bangladesh and Iran, which complicates the relationship between Muslim women and the hijab. Moving away from predictable interpretations that see the hijab merely as an instrument of Muslim women’s oppression, the essays here, from a variety of perspectives including historical, ethnographic, and political, demonstrate that not only have Muslim women covered/ or uncovered their heads for different reasons, but the head cloth itself has had different forms depending on the region or period of history.

Historically, in India, we have instances of both unveiling and veiling that have been initiated by Indian Muslim women. The early 20th century saw many Muslim women joining the national movement, giving up veiling, feeling this was the only way for them to change their own, and the country’s, future. Almost a hundred years later, the hijab continues to be a bone of contention in India, though in very different ways. On one hand, the rape threats that hijabi/non-hijabi women frequently encounter in the cyber world reflect the extreme desperation of the aggravated Hindutva millennials who are made to believe that unveiling Muslim women is their right while a large segment of Indian Muslim women are increasingly convinced that wearing the hijab is their constitutional prerogative.

The essays track the reasons why clothing, especially women’s attire, is very often a site of contestation and provide ways to hear and understand the ways in which Muslim girls or women make their own sartorial choices. They also offer ways of interpreting the stakes in banning the hijab in different parts of the world, and the implications of the ban on Muslim women, the wider community and the very idea of citizenship itself.

How did the issue of six hijab wearing young women in one college in Udipi become swiftly nationalized and internationalized as the sign of a “progressive” Hindu push against the tyrannies of Muslim patriarchy? How, moreover, were fervent cries successfully made for a “secularised” classroom exactly at the time when every aspect of public and social life in the state of Karnataka has been communalized? The ceaseless attacks by Hindu groups such as the Bajrang Dal and Sri Rama Sene, the VHP, the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti, and the myriad “outfits” spawned by the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh on Muslim beliefs, practices, and now livelihoods, reveals the larger frame within which the hijab issue became the tipping point.

How did Karnataka succumb so quickly to this muscular display of corrosive masculinity? The RSS worked hard over the last 100 years to achieve its goal of polarizing people on the west coast, where the economically successful Muslim has a presence. But what of the rest of Karnataka, where a mixture of induced fear and whole-hearted participation by the majority seems to be achieving the same effect? How has Hindu Rashtra become the sole visionary future for legions of young people? For one, there is a new and passionate righteousness to the language and gestures of the men, and some women, who participated in the harassment of Christian prayer groups last year, or willingly wore orange shawls in February this year. The giddy sense of psychic empowerment arises alongside gnawing awareness that education alone is no longer the guarantee of social mobility. Second, there is utter disarray among those social groups, and within those social movements—the Dalit Sangarsh Samiti, the farmers’ and the women’s movement—that had made Karnataka the site of novel social justice and development measures in the recent past. The brief flicker of a pushback, by Dalit men wearing blue shawls in Chitradurga at the height of the hijab protests, was swiftly suppressed. Thirdly, the cultural capital which could have been the basis for a vigorous regional pushback—the Kannada language—appears exhausted, given the aggressive demand for English, the growing presence of Hindi, and increasing state support for Sanskrit. Karnataka’s network of socially progressive Lingayat mathas, which have functioned like alternative governments in their respective regions, have preferred to retain their autonomy with their tacit support of Hindutva.

Following the prohibition by college managements in coastal Karnataka (and now elsewhere as well) of the use of the hijab in classrooms by young women students, BJP leaders and ministers in particular took great pride in being the purveyors of “secularism” in the classroom. Girls (and now boys have been conveniently added) should come to the college to study and not to assert their cultural/ethnic/religious identities or differences. At first glance, this seems like a blameless injunction—only the unmarked “secular” citizen/subject and the “uniformity” of the classroom can engage in the true pursuit of knowledge, and buttress a constitutional democracy such as ours. Now, armed with a High Court Order which has made uniforms the norm in colleges, the state makes itself out to be the robust protectors of law and order.

Yet, as we have seen, public space and public discourse in Karnataka is suffused with neo-Hinduness. The invocation by Home Minister, Araga Jnanendra, and the court, of the “secular” space of the classroom is, therefore, not just ironic, but diabolical in intent. It “rescues” the Muslim woman, oppressed by a patriarchal Islam of which the hijab is the prime marker, from her captors. Having for so long and loudly proclaimed, along with CT Ravi, Pratap Simha, K Eswarappa, Tejaswi Surya and myriad other elected BJP MPs and MLAs, that Hindu culture was in danger, the honourable Home Minister, while fearlessly sporting a red mark on his forehead, offers the Muslim woman “secular” protection in the classroom. It is into this same classroom that instruction in the Bhagavad Gita will be introduced.

As two spirited protests in Bengaluru, one on March 8 itself, asserted, the hijab issue was about Muslim women’s right to education. Their hard-won place in the classroom cannot be snatched away by either the Hindu or Muslim patriarchs. Whether Muslim women choose to wear the hijab or not—and let us be clear that both of these can be subversive actions at this time—they deserve their space as citizens of this democratic republic. They must fear neither their new “protectors” nor their adversaries. But for now, faced with the phalanx of institutions—of the Government, the law, the police, the media, and college managements themselves—that are ranged against them, when the “second-classness” of Karnataka Muslims has been declared in all but law, their struggles will be long and protracted. Women’s is the longest revolution indeed.