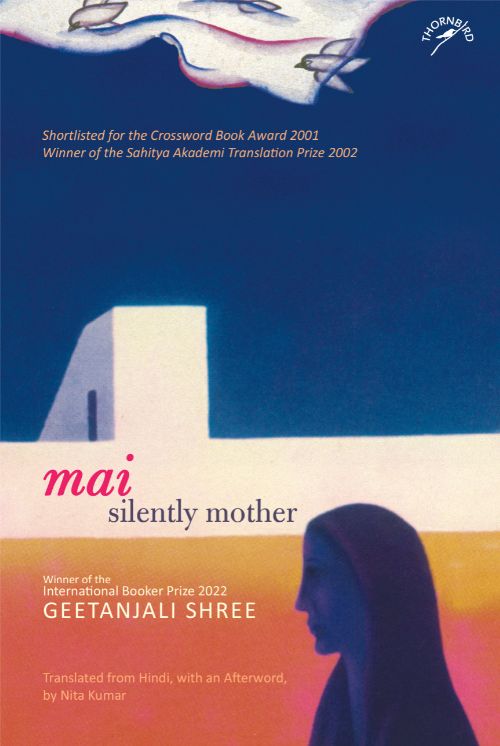

Geetanjali Shree’s Mai: Silently Mother (Niyogi Books, 2022), translated from Hindi by Nita Kumar uncovers, in a tale told in deceptively simple terms, using smells, sounds, tastes and flavours, scenes and tiny signs, and incidents of a daily and ordinary existence to build, weave by weave, a rich and layered tapestry, saying always more than is apparent.

At the centre is mai, the mother, seemingly weak and silent, but it is she who holds together the subtle patterns of relationships and agencies, and quietly carves out a life for herself as also for those around. Her New Age children are obsessed with rescuing her from the ‘prison’ and escaping themselves; but as the story unfolds, any simplistic notion of bondage and freedom goes for a toss. Profound stories of love and loss are lightly delivered.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Mai was my guide—for what I must not be.

Mai was trapped. She remained trapped.

Babu’s illness quietly swallowed up the little spot of contempt that had entered us and all we could feel was an infinite sadness well up inside. In spite of that woman. Or maybe because of her.

We had not learnt to ask questions. We just stood quietly on one side, casting a pitying look at mai.

We felt pity for babu too but the truth is that babu was only an expansion of mai for us. If he existed at all. He was tied up with her.

And mai, in our sight, was tied up with us. In spite of everything that we had seen.

There is a trap formed by words, indeed one formed only by thoughts, in fact one formed merely by the tiniest doubt. The person thus entrapped sees everything only in a certain colour, even things of quite a different colour.

Our sight had been sharpening since childhood. The faint ticktock of some unfamiliar clock was audible but as if our ears were deceiving us. Some unseen flutter did reach us, but we considered it an illusion. If we saw some unfamiliar glimpse of mai we blinked our eyes in surprise and then re-drew our old familiar image.

Or one can say that regardless of what we saw or heard, we knew only this—that mai was captive, sad, and helpless. And we— we were born to save her.

But while lying on the roof with our eyes closed and repeating our old ideas, if we opened our eyes, the bright sky would fill our insides and something sharp would pierce us, something dangerously like questions.

It could be that the truth is so vast and so tangled that, unnerved by this, we would prefer to take some small, shrunken fiction as true only because of its simplicity.

And it is also that a trait or characteristic can be recognised in a relative stranger, but on knowing the person better it gets mixed up with many other traits in him and becomes unrecognisable. If that person who nana introduced me to had seen me everyday, maybe he would not have said—‘Oh, is this…Rajjo’s daughter…?’?

We are so hesitant before vastness, before its unknown waves… But why should we not fear the unknown? We can go ahead because we know, otherwise would we not be immobile in one spot? It is life’s own condition that you imagine you know and keep moving. That moving on is then called life.

We understood later that it is not only we who moved. Life itself moves on, at its own speed. The speed is the same for the person standing still in the storm and for him moving along on his own. It is not we who are moving life along. Or that life stops moving for the person who has stood still.

We saw mai standing at one point, and made her stop still there forever.

Like the visitors to the house who, in spite of the passage of many years, fixed me forever in some familiar moment of my childhood. For them I was the one from somewhere back then. Faltering before their eyes, I would myself put on that cloak of childhood. My dimensions may have been an adult’s but I would pull myself into becoming small again and perform accordingly. I felt sometimes that I was living a lie in that house. I would panic. Run away, let the lie not be known.

But I could not leave mai in the clutches of that house and go away. I stayed on. Subodh wanted to have an exhibition of my paintings in England. He was confident that the foreign audience would be impressed by the subjectivity of an Indian woman and love my paintings. He was hopeful of a terrific success.

But how was all this to come about? Mai could not be left to her fate. Subodh could not return. I could not stay there forever.

Mai mentioned my work. ‘Does a freelancer not need a college or institute?’ I should think of my career; everything would go on as usual in the house. Then she left the room hurriedly as she heard the tapping of babu’s cane.

Babu no longer left the house to go anywhere. The scooter stood covered in tarpaulin awaiting Subodh’s return. Babu would keep reading. Until some visitor arrived. Or he would call mai. She would keep sitting near him.

I rarely went to babu. Subodh at least could talk about things. Such as how the Asians settled in England were experiencing ill will against them. And so on…

I could not think of anything to talk about. The status of painting in our house was dirt, so it was not a subject for conversation. I also found it difficult to follow babu’s speech after his accident and felt embarrassed to keep asking again and again, ‘What?’ ‘Tell me again?’ ‘I didn’t get it?’

I could neither stay nor leave. If I went I came back very quickly. If Subodh left he immediately started planning to come back.

In fact the house had become home again, for better or for worse. And we were getting stuck in the peculiar subterranean mixture of security, safety, and suffocation.