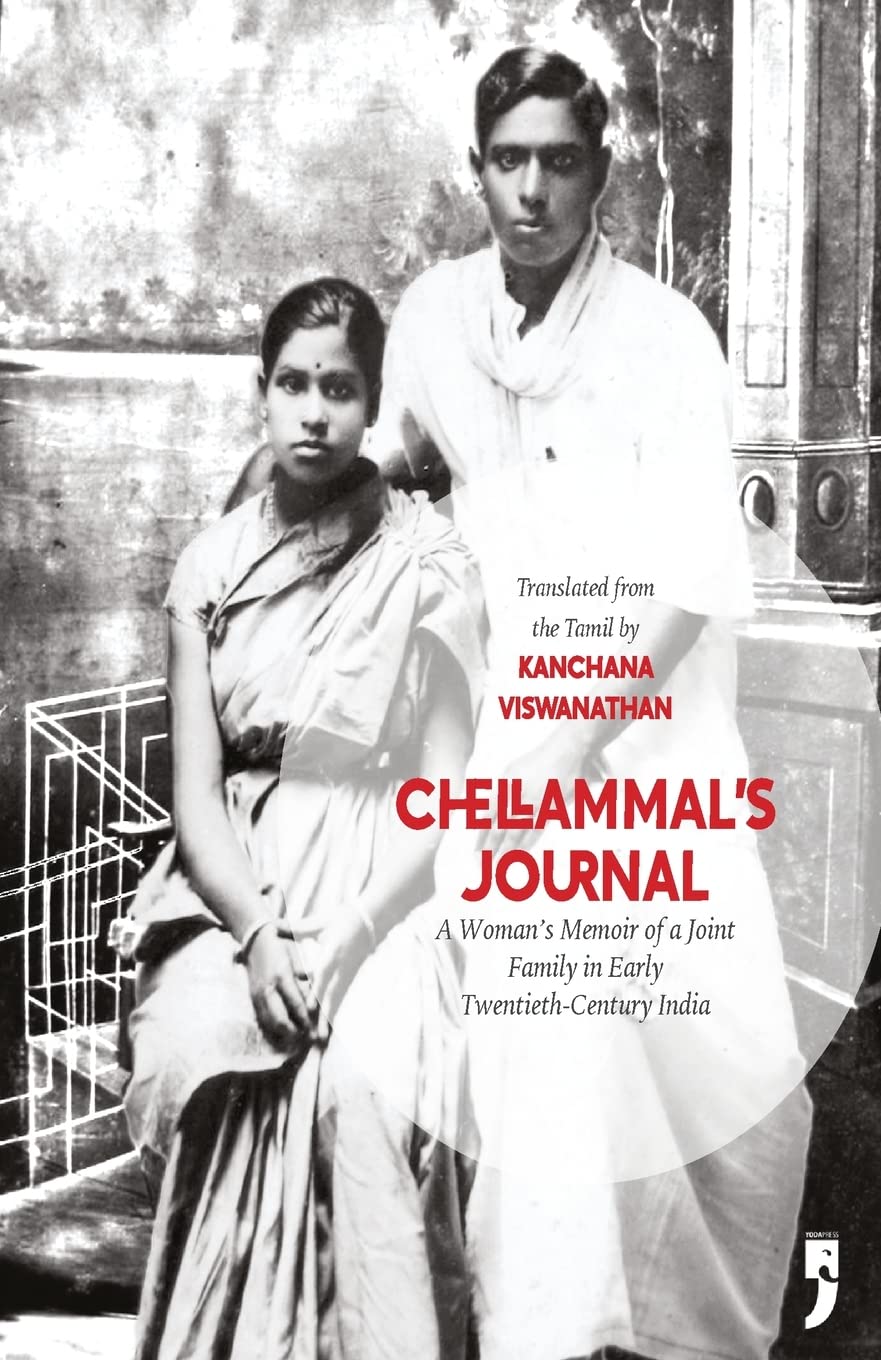

Translated from the Tamil by Kanchana Viswanathan, Chellammal’s Journal records the journey of a woman in an upper-caste joint family in early twentieth-century Nagercoil, Tamil Nadu. In her memoir, Chellammal is especially sensitive to the treatment of young widows in Brahmanical Tamil society and questions the society that places its women under tremendous scrutiny.

Written at a time when dissent or disagreement by women in Chellammal’s circumstances would have been frowned upon, her daughter’s translation brings the narrative to life for non-Tamil speaking readers for the first time.

The following are excerpts from the book.

From the Foreword

– Kanchana Viswanathan

These memoirs not only express a woman’s pain, anguish and agony, they also give voice to the voiceless—all the young girls, wives and widows—for whom life was so difficult, so full of disappointment and disrespect, all who suffered in silence. In her narrative, she has interspersed descriptions of memorable events in her life with her reflections on the plight of women, both in the context of her situation and in general. I felt that the content is still very relevant to women all over the world, whose aspirations and potential are ignored and whose needs are suppressed because of societal, religious and political pressures. (Having lived and worked as a physician in the US for many decades, I have noticed this first-hand, time and time again.) The challenges faced by women are universal and still very serious, more than a century after my mother’s early life experiences.

Chellammal seems to have deliberately repeated her views on social issues that affected her deeply, in different sections of the manuscript. She comes back several times in her narrative to the theme of the mistreatment of widows by the orthodox Hindu society that she was part of in her younger days, where young widows were forced to withdraw from society and live a painful existence in the shadows. Her disdain for this practice seems to have been shaped and reinforced by her witnessing the plight of her older sister, who was widowed at a very young age. Amma saw many powerful women in her own family: her widowed grandmother who continued to take care of her body by oiling it, bathing with Pears soap and who was financially independent, and her own mother, who ran the house wisely. Many others broke norms in her family and the society, even before her time, and yet she keeps going back to widows and the indignities they suffered because the images of her mother and her sister are indelibly etched on her mind. The popular TV serials, which she seems to have been in the habit of watching, also harped on the politics of the family, conflating the past and the present in a way that erased all conflicts, changes and resistance. In her writing, she refers to these serials at various times to bring force to her argument.

[…]

I started my periods six months after the wedding. In accordance with the then prevailing custom, the occasion was celebrated with great fanfare. For the main event on the third day, men and women from the husband’s house usually attended, along with a few neighbours. They would be fed and then they would give money to the young girls who were also usually present, providing company to the girl who has attained menarche. It was customary to invite five to six young pre-pubertal girls (usually ten-year olds) from the neighbourhood and have them stay for three days with the girl who had come of age. They were called “Girls in Residence.” They were given money and were well taken care of. They got good meals and snacks. Even I have participated in this event when I was ten. It used to be fun—plenty of snacks and also some money. In return, the girls would keep company and play all kinds of indoor games with cowrie shells with the girl who had come of age. Also, they did not have to attend school—the argument always was that it was okay if girls missed two or three days of school. These young girls would sing very raunchy songs describing intimate acts between the girl who had attained puberty and her husband.

The songs were quite explicit and vulgar. I feel rather ashamed to elaborate. The adults wrote the songs but there was no way the girls who sang the songs would not have understood the meanings. A typical song described the different ways the man enjoys the woman’s body. It never mentioned anything about how a woman could enjoy the man’s physique and seemed to imply that the woman was created for the man’s pleasure. In those days, men considered women as objects that existed solely to satisfy their desires. The women seemed to consider it their duty to fulfil the man’s lust. That resulted in the women giving birth to many children, one after the other in rapid succession. Their whole life’s mission seemed to be to live for their husbands. In Puranas you encounter men marrying several women. Even the gods are each depicted as having more than one wife. No other religion depicts divinity in such a derogatory fashion. In the Hindu religion, on the one hand, they describe god as something/someone with no designated form or feature who is everything and nothing, omnipresent. But on the other hand, gods are described as men with emotions like anger, love and all the other desires of ordinary human beings, who also marry and have children. Worshippers treat gods like ordinary human beings by making offerings to them, in return expecting help with their own needs and desires. I feel such acts diminish the divine. Or maybe I do not get the inner meaning of it all. What I consider as degradation may be considered noble by others.

Then you have this terrible custom of ill-treating widows, which seems to be more prevalent among Hindus. At one time they burned the widows alive along with the corpses of their husbands. Thanks to the social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy, that custom was abolished and made illegal. However, even today it seems to be happening in some remote villages of Rajasthan. The result seems to be that instead of burning them alive, widows are destroyed in every possible way. Like I have said earlier, their jewels and auspicious symbols are taken away and they have to remain indoors in a white sari for a year. They can’t even visit close relatives for a year. I have already written about how the status of widows has improved in the present times. I continue to harp on this subject because I want to emphasize that a woman is not in any way inferior to a man. If there is no woman there will be no man either. Women are as much emotional beings as men. I also believe that women are more intelligent than men but they are treated like inanimate objects.

Among Brahmins, there were young girls who were widowed by the time they were five to seven years old. When a child widow attained puberty, the parents would shave her hair and keep her indoors. I have seen such women. The famous writer Kalki had written a story graphically describing this injustice. I enjoyed reading Kalki’s stories and essays. He was a great writer and was one of the eminent personalities who fought for independence from the British. He wrote extensively on various flawed social practices like untouchability, superstitions, child marriage and the plight of widows. He wrote with an element of biting sarcasm, and he would make you think and empathize.

Widows were not allowed to participate in festive celebrations, but they were always in the background toiling to make all the sweets and other eatables. In those days whenever there was a wedding, there would be at least four or five young widows in the back patio, the most remote end of the house, who would have been assigned to do some work or the other. They were unpaid labourers. However, they did their work happily as that seemed to be the only social outlet for them.