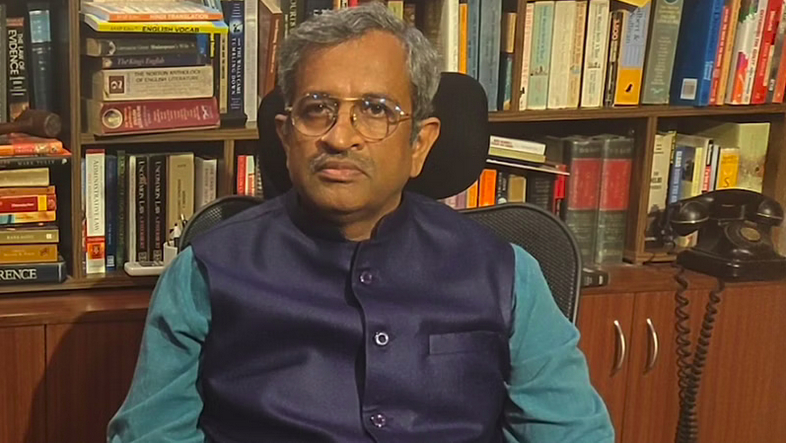

The role of the courts in accelerating the mandir-masjid dispute seems to be on full display with the ongoing controversy over the Gyanvapi mosque. Why was a civil judge in Varanasi allowed to order videography of the mosque? It was vehemently opposed by the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Management Committee, which looks after the mosque. The Anjuman took the matter to the Supreme Court, which has turned down its plea to order a status quo on the survey. Supreme Court senior advocate Sanjay Hedge explains the details of this case.

Why did the court agree to entertain the Gyanvapi mosque case, given that the Places of Worship Act, 1991, does not permit any changes in designated places of worship?

Our legal system is designed in such a way that any plaintiff can ask for final or interim relief on any matter. There may be circumstances where the court gives interim relief. In the interim stage, it is difficult to figure out the final outcome of a matter. In the interim stage, a court is more keen to maintain the status quo, even if it gives an unfair advantage to the dominant side.

But by reopening this case, it seems as though we are witnessing a return to the Ayodhya mandir-masjid dispute?

The Ayodhya agitation seems to be recurring again, and we are witness to it in the present Gyanvapi mosque controversy. The Ayodhya agitation was in cold storage for 30 years, and then it got revived. There are similarities between the two cases, as also differences. The present Gyanvapi controversy is taking place under the full glare of the media and social media.

Why was this suit not dismissed because it infringed on the Places of Worship Act, 1991? Does a narrative now seem to have been built around a Shivling in the Gyanvapi mosque?

The courts will go by the case before them. There is the Places of Worship Act, 1991, which prohibits [the] change of any place of worship. An application was ordered and was barred under the 1991 Act. But the matter was allowed to linger. Interpretations are being given to this Act, which do not totally bar civil or other proceedings. The social impact of this is difficult to establish. There is a majoritarian sentiment prevailing in the court, which would not allow a judgment to be given even with forensic evidence being provided to the court. People like me have stated that a forensic examination must be used to establish the truth.

The Archaeological Survey of India has been asked to examine the structure too!

The ASI examination (brought in earlier) had been given a stay.

What do you think about the Supreme Court’s decision to transfer this case from a civil court to a district court?

The Supreme Court has transferred the case from the civil court to the district court. At all levels of the judiciary, we must take into account that judges are also lawyers. After all, where do judges come from? They will reflect what is happening in society. If society goes into a frenzy over perceptions of the past and future, the courts will not go counter to this majority opinion. Judges often mirror the prejudices of society.

If the courts fail to give us direction, then on whom can society depend?

The public must fall back upon itself. Other institutions of government will necessarily follow that course. There is little chance that the courts will go opposite to this [the public’s viewpoint]. If we look at the history of democracies, the courts have not gone against the temper of their time. Though they have, in some cases, put a break (which has been effective) for some time.

But what do you feel about these recent developments in the Gyanvapi mosque case?

I would not like to put on record a personal view because, at some time, I may have a role in the matter. The lower court went looking for visual evidence of some past Hindu structure. The problem with being given the approval to do videography was that if anything looked similar to an idol, it would have been recorded. If the court commissioner had asked then and there what the structure was, and it had been explained to him that it was a fountain, this controversy would not have erupted.

Does it seem all sides are to blame for the present situation?

Court proceedings can be interpreted in many ways. It is not appropriate for me to comment on this.

But to go back to the Supreme Court, it seems it was unwilling to take an immediate decision on this case.

The Supreme Court has acted consistently with the court’s rules, which is that the lowest court should decide. If any party is not happy with a lower court’s decision, then an appeal is possible. If the Supreme Court had been left to make a decision, no appeal would have been possible.

Can you elaborate on this?

To cite an example, in the 2002 Gujarat riots, the SIT wanted closure to the case, but the amicus curiae demanded a further investigation, and the Supreme Court decided it would like to peruse the closure report and send it back. This has been the practice with decades of SC rulings.

But have they only served to whip up more communal tensions?

The real question is whether the Supreme Court is sticking too precisely to the law. And by doing so, whether, as in the case of the Babri masjid dispute, this played a part in the destruction of the masjid. And how this set a stage for similar occurrences at a future date.

The then Chief Justice MNR Venkatachaliah accepted the solemn affidavit given by the Uttar Pradesh state government led by then chief minister Kalyan Singh that no harm would come to the disputed structure. There was no legal room for the Supreme Court not to accept that, but despite this undertaking, the mosque was brought down. Compare this with another chief justice, SP Bharucha, who prevented the government of Karnataka from releasing associates of sandalwood smuggler Veerappan from jail in return for the release of the popular Kannada film actor Rajkumar. When told that this order could adversely affect law and order in Bangalore [now Bengaluru], which has most of India’s software industry, he told the Karnataka government that they should learn to govern or quit.

Following this judgment, the government was able to solve the problem of Veerappan in a few months. Sometimes firmness prevents many more problems from fracturing the future.

The Hindu right-wing is talking about bringing down 3,000 mosques. Where will this end?

I have no idea where it will stop. We are going on the path whereby a certain part of our heritage will get demolished. It is the same trajectory that led to the manner in which the Taliban destroyed the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan.

That is why, in 1991, Parliament brought in this [Places of Worship] Act to preserve the status quo of all monuments from 1947. It was the cut-off year, except for the Ram Janmabhoomi case, which was already pending in the court. And yet courts have been used as instruments to tear down the agreed-upon status quo.

BJP MP Subramanian Swamy has moved a petition in court to repeal the 1991 Places of Worship Act.

The Supreme Court can decide on the validity of the Places of Worship Act. Parliament must take a call on whether to replace or substitute it. Where Parliament has feared to tread, why should courts go there? This is not to say that this law cannot be repealed.

Do you see that happening in the future?

I don’t speak for the BJP. What Parliament can do, Parliament can also undo. I must emphasise that the courts reflect the society of their time. If a society does not make a right decision, then what can courts do? If the public wants to bring down one structure after another, the courts will hardly be able to stop this.