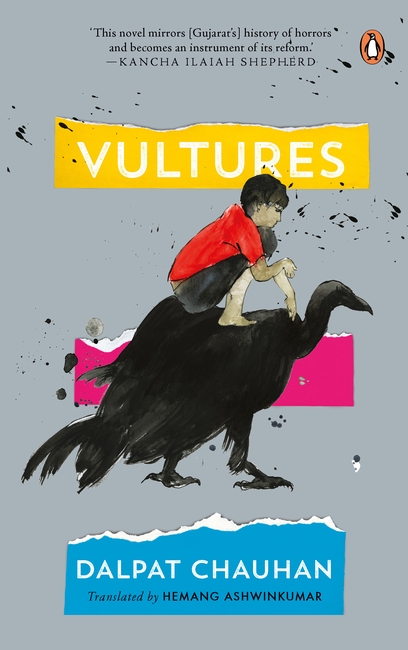

Gujarat, 1964. The agrarian system of renewable annual contacts mandates fulltime labour in the houses and farms of landlords. In these bleak circumstances, Iso, a tanner by birth, graduates from being a child labourer to an adult serf on the estate of Mavaji. His life is one of humiliation, hunger and drudgery, and the only respite comes in the form of Diwali, Mavaji’s daughter. Between them exists a physical relationship that is shrouded in secrecy, shame and fear. Even as Iso creates distance between them, a chance encounter turns to violence and tragedy, and he faces the brutal sword of caste patriarchy.

Based on the blood-curdling murder of a dalit boy by Rajput landlords in Kodaram village in 1964, Vultures portrays a feudal society structured around caste-based relations and social segregation, in which dalit lives and livelihoods are torn to pieces by upper-caste vultures. The deft use of dialect, graphic descriptions and translator Hemang Ashwinkumar’s lucid telling throw sharp focus on the fragmented world of a mofussil village in Gujarat, much of which remains unchanged even today.

The following are excerpts from the book.

Introduction

-Hemang Ashwinkumar

I will never be free of memories. Memories are my reality. That is the destiny of Dalits.

—Bhimrao Ambedkar

‘Two Imaginary Soliloquies: Ambedkar and Gandhi’,

D.R. Nagaraj, Flaming Feet and Other Essays, 2010

To hear one of the greatest intellectuals of modern India let out a cry of profound anguish—on the eve of the Golden Jubilee of Indian Independence—over the lot of his people to forever be the prisoners of memories is rather disconcerting but also intriguing. The memory he is talking about is neither the historical memory nor the spiritual memory, for he had delegitimized the projects of excavating these memories as shrewdly colonial and sinisterly assimilationist, respectively. If he knew the quest for glorious Dalit past and proud genealogies to be constructs—the revivalist cultural politics to him was dangerously status quoist—he would have none of these structures of memory. The claustrophobic prison-house of memory he is condemned to relates to the frozen time his community is forced to inhabit; the unchanging time marked by the poisonous, viral caste ethos that has infected the very institutions and forms of life he had built and enlivened to fight it.

Like Babasaheb, Bhalabha, the visualizer in Vultures, in whose memory the narrative unfolds, is a hostage to his memory. Based on the incident of the blood-curdling murder of a Dalit boy by Rajput landlords of Kodaram village in Banaskantha district in 1964 and published around the Golden Jubilee of Independence, the novel portrays an orthodox, feudal society, structured around caste-based relations and social segregation. Bhalabha’s memory categorically disputes the revivalist and even anthropological strands of Dalit cultural memory. It’s quintessentially the bitter-sweet memory of his community’s existential predicament, of the knowledge that in the midst of apparent, superficial change, nothing has changed. He realizes that the vice-like grip of caste, entrenched in its deep-seated material greed and its dictates for social distancing, has not only struck deeper roots but also spread its rhizome network far and wide, infecting communities, structures, institutions and world views.

[…]

‘Why are you emptying pots? What happened?’ he asked.

‘To fetch water. Why else?’

Maani stopped and looked at him suspiciously, as if asking for an explanation.

Bhalo obliged. ‘I have not recently heard of a running waterwheel anywhere in the village. And this year, the kutcha well reserved for us has run dry. I am wondering where you will fetch water from.’

‘Don’t you know Lavaji’s waterwheel was working through the night?’ Maani snapped back at her husband, irritated more at the daily ordeal of begging for water than Bhalo’s ignorance. ‘There will be water in the drain, if not in the reservoir. I’ll take a small bowl along.’

‘God knows when our water woes will end,’ sighed Bhalo. ‘Begging from well to well and village to village—how harsh a decree has been inscribed on our accursed lot!’

At Bhalo’s lament, Maani too turned sombre, and she resumed cleaning the pots without a word.

Once the small pot was ready, emptied and cleaned, she gently placed it on the floor. Then she took a small bowl of German silver from the stand and stole a glance at her husband, who was standing still dreamily.

Bhalo was once again lost in thought. If only they had a pucca well of their own! Of course, there wasn’t a single pucca well in the entire village, but then those people had many wells to draw from. They also had serfs and sharecroppers in their fields who could fetch water for them, even from long distances if required. But what did Bhalo and Maani and the others out here have? Nothing more than a kutcha well in the wasteland that dried up every summer. And even when it had water, it was polluted with cow dung and kerosene, as punishment for their alleged transgressions.

Maani set the small earthen pot on one side of her waist, its neck held in the crook of her elbow, and covered its mouth with the German silver bowl. In her left hand hung a slightly bigger pot, her fingers thrust into its gaping mouth. Ready to leave, she turned to Bhalo.

‘I am going to fetch fresh water,’ she said. ‘We have already stored the water for rinsing and scrubbing in the waist-high earthen pot there; I brought it from the drum-beaters’ well the other day. Now stop standing there like a stump and hurry up.