Award-winning author and journalist Vaasanthi writes in both English and Tamil. Her work over forty years and more include novels, short story collections and travelogues. She has written popular (and occasionally controversial) biographies – including Amma: Jayalalithaa’s Journey from Movie Star to Political Queen, The Lone Empress: A Portrait of Jayalalithaa, Karunanidhi: A Definitive Biography, and Rajinikanth: A Life. Her works in Tamil have been translated into Malayalam, Hindi, Telugu, Kannada, English, Norwegian, Czech and Dutch. She was the editor of the Tamil edition of India Today for nearly ten years in Chennai.

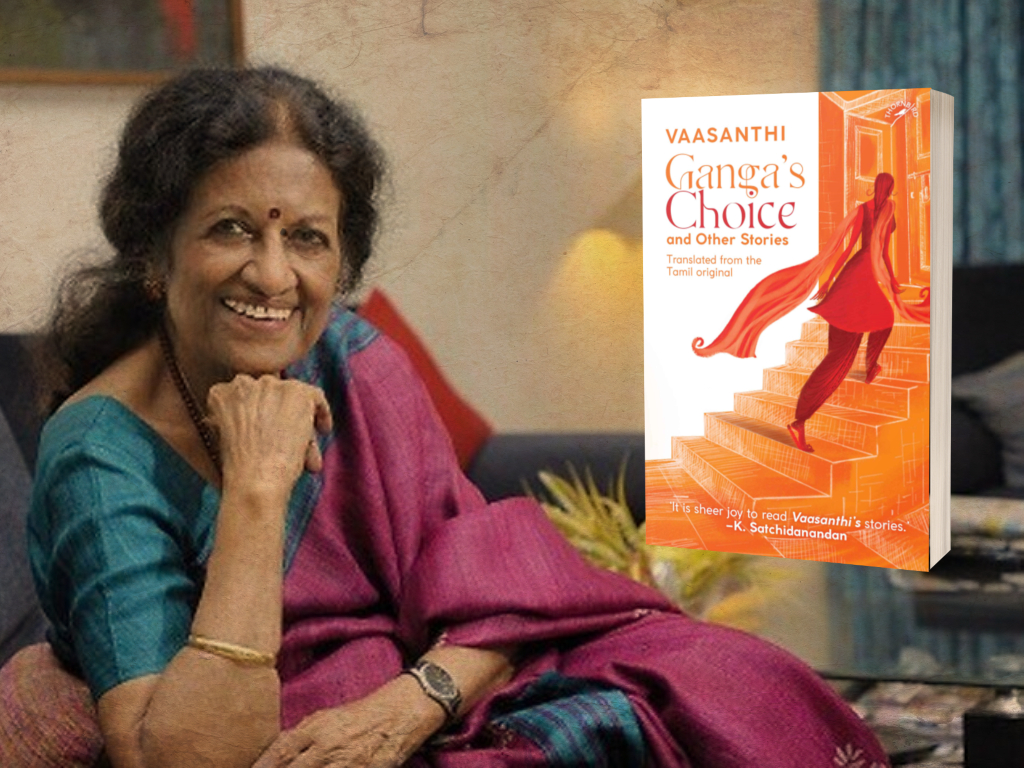

In this conversation, she speaks to Githa Hariharan about her short stories, with specific reference to Ganga’s Choice and Other Stories, a collection of stories translated from Tamil into English by the author, Sukanya Venkataraman and Gomathi Narayan, and published by Niyogi Books in 2021.

Githa Hariharan (GH): The stories in Ganga’s Choice and Other Stories look closely at women’s acts of resistance, but never without probing the human costs of choice – how difficult it is to cut loose, even impossible sometimes. Indeed, the stories portray women who are defeated by fear, as well as women who manage to overcome their fear, even if only for one triumphant moment. Would you say your stories make a painfully realistic assessment of the choices available to women?

Vaasanthi (V): I write about what I see happening around me. What I have observed in the course of my life’s journey as a member of a large conservative family in my childhood, and as a daughter, a mother, a wife, and a journalist. Also as a citizen of this country, a citizen with dreams and expectations and hopes for a better future. Fiction writers draw from lived or heard experiences, or something they have witnessed and been moved by. My fiction writing began during my college days. It centred round the family and on gender discrimination within the four walls of home. The sorrow of the childless woman, the miserable life that widows live but silently accept as their fate – I wrote about these and other unspeakable wounds women have endured.

As a journalist, I had the opportunity to travel the length and breadth of Tamil Nadu. During the nineties I was the editor of the Tamil edition of India Today and I lived in Tamil Nadu at a stretch for the first time. (I grew up in Karnataka and was never in Tamil Nadu though I became a writer in Tamil.) My travels as a journalist in served as an eye opener. I saw, close up, a world I did not know – different cultural hues of course, but most sharply, the condition of women in different rural settings, the patriarchal pressures on them, and the mythological beliefs that are always directed at suppressing their freedom. The women I saw, the most vulnerable rural women, illiterate and dependent, were caught in this web. I could sense their anger and frustration at not being able to free themselves of this web. All these impressions that I gained as a journalist stayed with me, in my memory, you could even say in my subconscious level of awareness. They emerged later when I was writing so I could weave them into short stories. This is how stories such as “Murder”, “Poison” and “Dance of the Gods” were born.

The young women who had migrated from villages to cities and worked as maids told me a different story. They too suffered from patriarchal pressures, they experienced class alienation. But the economic independence they enjoyed to a certain extent made them bolder, and they could take decisions defying the accepted order of things. Writing about these people revealed to me the many stories hidden in their tears and silence. There is a redeeming factor in how they deal with their pressures. This is what stories like “Ganga’s Choice”, “Voice” and “Mouse Trap” capture.

The stories had to be realistic. Some stories write the end themselves as in “The Testimony”. I thought that was the honest way to portray them. I cannot write fairy tales. Yet even in a tragic ending, there is always a stream of hope. There is an undercurrent of redemption that comes through their realisation of oppression, through the rebellious thoughts in their minds, and through the various reactions the characters have to these thoughts. Even a woman putting an end to her life – even her suicide is an act of protest and fury , a gesture of defiance as in the story “Dance of the Gods”. The protagonist Panchali thinks of the many cages in the village, one for women during their menstrual cycle, another the kitchen. The cage is a metaphor that describes the status of women in our villages. These are cages women have to fight all their lives to emerge from and be free. I don’t know how many women truly get to rebel and be free of the cages they live in, but my Panchali does. It is in the kitchen, in the end, that Panchali finds her route to escape from public humiliation, ridicule and betrayal. Her death is an expression of her refusal to succumb to the heartless patriarchal system.

GH: Your stories seize the contemporary moment, from the vilification of Muslims as terrorists, to the human tragedies created by the covid lockdown. Is this the news-conscious journalist in you providing stories for the present moment?

V: Perhaps you are right. I began my career as a fiction writer. As a girl, I was deeply influenced by my maternal grandfather who was a Gandhian and an English teacher. He was a liberal, always deeply disturbed by discrimination in the name of caste, class, gender and religion. I developed an academic interest in the history and sociology of various states. For instance, I happened to reside in the North Eastern states of India when my [Engineer] husband, a Central Government employee, was posted there. I found that the rest of India including the Centre were ignorant of the anger and aspirations of the people there who were ethnically different. When we were posted back to Delhi, I was thirsting to write journalistic articles on subjects that the Tamil readers were not familiar with. I was already a prolific writer of fiction in Tamil, and when the Tamil magazines requested me to write about events in the capital – Indira Gandhi’s assassination was one – I began to write quite a few journalistic articles in Tamil along with my fiction writing. It was a learning process. It helped me delve deeper into the way things unfurl in the political world and how the world keeps changing. From then on I began to feel that no writer could remain apolitical.

I have been very deeply affected by the vilification of Muslims as terrorists – it is like a stigma that seems to have been stuck onto the community deliberately. The fear and sense of alienation felt by my Tamil/Kannada Muslim friends; their mental agony and shock, all so clear in their silent gaze; their feeling of insecurity increased manifold: How can a writer not write about all this, describe and analyse such a social crisis ? The images I saw of migrant labour walking to their villages during the Covid lockdown left me devastated – I was agonised to a degree that I could not explain. I had to give vent to my feelings. Call it news-conscious or whatever, it was a natural reaction of a sensitive writer who takes things to heart.

GH: In this collection, I found the recurring contrast of urban and rural settings striking. In fact, the theme of the dislocated ‘immigrant’ seems to run like a linking thread throughout the collection, intersecting, of course, with gender, community and class. Would you like to comment?

V: Ours is a country of great contrasts. There are great divides between the urban and the rural, there is the gender divide, the communal divide, the class divide – division is all-pervading in the country no matter which language you speak in. In a society that is becoming more and more unequal in every way, we become, metaphorically, immigrants – crossing over borders, over the line of control, breaking walls constructed by the system – first the family, clan and tribe, then the state. Crossing borders is a constant endeavour manifested in many forms of defiance; paradoxically, some of these forms may appear cowardly or defeatist. But the fact that we endeavour is what is reassuring.

GH: A question on craft: many of the stories, if not most, are open-ended, so what happens after could be this or that story. Is this a deliberate challenge to the reader?

V: I like to leave the stories open-ended. Of course it depends on the subject you deal with. The end of most of my stories comes on its own – the stories write their own last sentence as it were. I wouldn’t know how else to end. There is no end to any story in one’s life, really. Life moves on, and the reader can imagine the unsaid in whatever way she wants.

GH: The stories travel all over India and speak powerfully of contemporary India. Would you say the changes you portray are generally for the worse? From poverty to inequality to the active exclusion of people, what sort of assessment do your stories make of the country today?

V: Creative writing to me is not only an aesthetic, artistic craft, but also a political act. I have been lucky to have travelled in most parts of India, and have been overwhelmed by the feeling of oneness with people of different regions speaking different tongues. I grew up in Karnataka, in an amazingly secular inclusive atmosphere, and still carry the richness of the experience in my heart. I am pained when I see that the scene has changed. As a journalist and a creative writer, I am deeply conscious of my duty as a writer. I am aware of what is going on around me – economic and gender inequality; the growing fear experienced by the minorities; or the draconian sedition laws that still exist from colonial times, and that often get misused by the state. Writers write about what affects them deeply; they try to decipher the meaning of what they perceive. That is my effort in these stories – I am trying to understand why people behave the way they do. It is a fascinating journey, at once humbling and baffling. I believe there is always a ray of hope in the writer’s mind. We are always looking for a glimmer of redemption and retribution. A reviewer said of my stories that they ‘conclude on a certain tone of triumph – sometimes darkly shadowed – (but a) triumph of a sort, nevertheless.’ The humane, in one form or the other redeems not only the characters but also the readers.

I have faith in the youth of today who are more intelligent and better informed than all of us when we were young. They are politically aware and conscious of what is wrong and what is right. I hope and believe there is light at the end of the tunnel and beyond. I continue to write because I dare to hope.