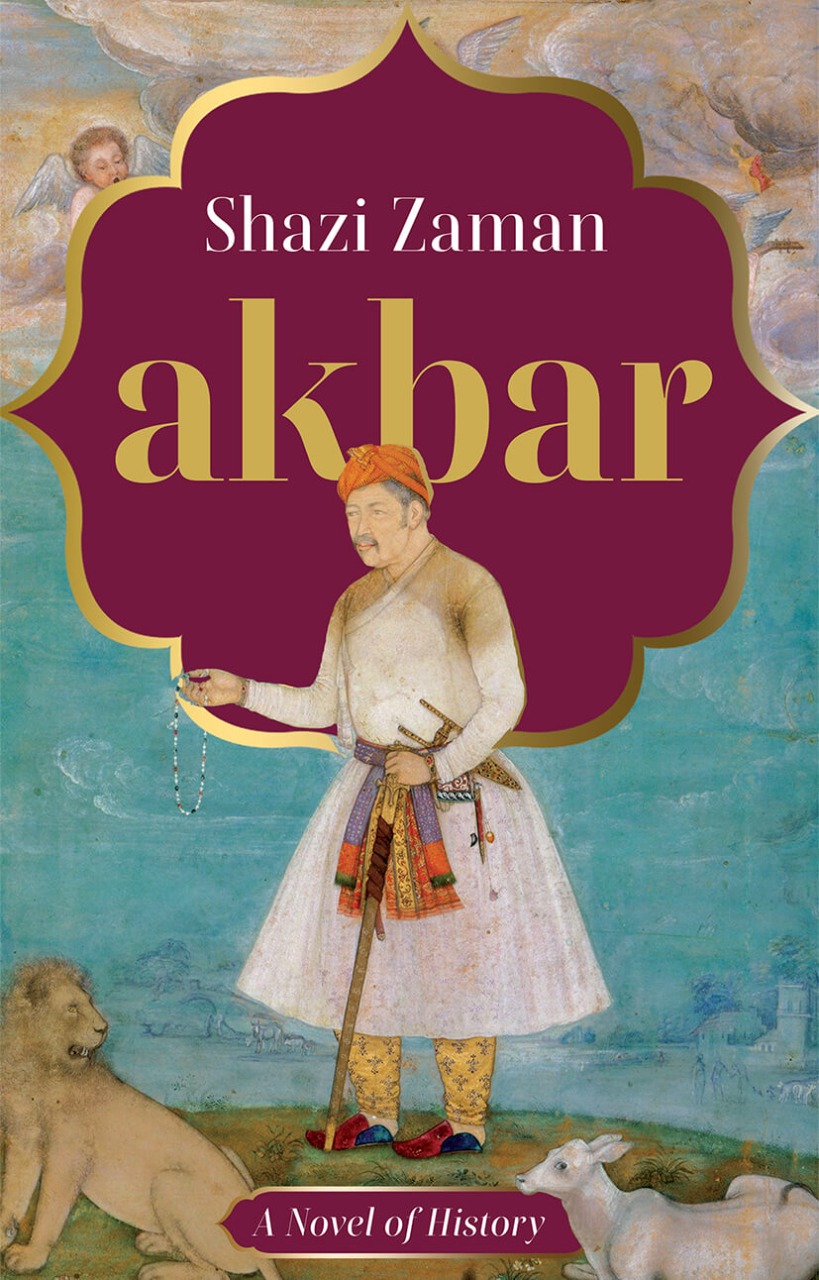

Conventional historical accounts tend to paper over seemingly minor events related to Akbar’s life, to the detriment of a comprehensive appreciation of one of the most important figures of Indian history. Shazi Zaman fills the gap with this remarkable novel rooted in history.

Akbar’s writ ran from the Hindukush in the west to the Bay of Bengal in the east, an empire his father Humayun and grandfather Babur had only dreamed of. And his religious policy, boldly unorthodox, was as fierce a contest with the clergy, particularly Islamic, as were his military campaigns with his political opponents. Most histories give us Akbar the commander who never lost on the battlefield, and the fearlessly iconoclastic ruler. But we rarely come across the restless, questing soul who wished to reconcile a sensitive and compassionate heart to the sometimes ruthless obligations of statecraft; and the man who, in his struggle for sulh-i-kul, peace with all, could dare to treat as equal not only all faiths—Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Jainism, Zoroastrianism and others—but all life as well—human or animal.

Read an excerpt from the book.

In Fatehpur Sikri, near the hospice of Sheikh Salim Chishti, was an abandoned building which was once the cell of Sheikh Niazi. The place came to life again when Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar built the Ibadat Khana here. Those days Badshah Salamat would pray in solitude. In the morning he could be seen sitting on a stone slab of an old cell. This cell was near the royal palace but there was no habitation behind it. Mullah Abdul Qadir Badayuni says that Badshah Salamat won so many victories that he began to sit here to thank God. But this was not the only reason. Badshah Salamat was a free thinker at heart.

He would look at each religion and each sect with an open mind.

He would say: ‘Although I am the master of so vast a kingdom, and all the appliances of government are to my hand, yet since true greatness consists in doing the will of God, my mind is not at ease in this diversity of sects and creeds, and my heart is oppressed by this outward pomp of circumstances. With what satisfaction can I undertake the conquest of empire? How I wish for the coming of some pious man, who will resolve the distractions of my heart.’

A wide variety of ideas would occur to Badshah Salamat and he would express them— ‘The faqirs of Hindustan say that keeping death in mind, we should do good work. Not to think of life and one’s youth. But we think that good deeds should be done without thought of death. So that we do good just because they are good and not for fear or hope…

‘We don’t find any reason in the people of Hindustan blowing the conch or ringing the bell in worship. This must be as a warning or a reminder…

‘Treading the path of reason and rationality is far above the logic that this humble self can come up with. If past practices were meant to be followed, the prophets would only have walked in the footsteps of the previous prophets.

‘Being a pir means having the power to know and cure the suffering of people, and not growing a beard, wearing a long coat and creating a furore over worldly matters.’

Around the twentieth regnalyear, corresponding to 1575 ce, in the month of March, Badshah Salamat gave orders to build the Ibadat Khana—the House of Worship—near the AnupT alao. It had four porticos. When completed, a dhrupad was sung to congratulate the Emperor on the construction of this new temple—

Congratulations on the building of a new temple,

Wish you a thousand years of rule, Your Majesty.

Instead of writing in praise of those who can’t see the future,

We make effort to learn the mystery of the Emperor who himself

knows the mysteries of music;

Live eternally like Lord Indra;

The society would reform through his body,

Which has been made in the fire of the twelve gunas.

Badshah Salamat said, ‘We have organized this assembly so that the facts of every religion, whether Hindu or Muslim, be brought out in the open. The closed hearts of our religious leaders and scholars

be opened so that Muslims know who they are. They are unaware. They only think of Muslims as those who recite the kalma, consume meat and perform sijda by prostrating themselves on the ground. Muslims in fact are those who wage jihad on their self and control their desires and temper, and surrender to the rule of law.’

Raja Birbal had recited a poem to Badshah Salamat which said:

When we can offer jaggery and sugar made of sugarcane to the gods,

When cotton flowers burst to give us clothes to cover ourselves,

When jute plants rot to give us paper on which the Quran and

Puran is written,

In like manner, poet Brahma says to Emperor Akbar, could the

broken and the rotten be shown the right path.

But this reform was not easy. Once when Badshah Salamat had organized an assembly in the honour of Sheikh Ziaullah, the son of the prominent Sufi Sheikh Muhammad Ghaus, in the Ibadat Khanaand called the sayyids, the sheikhs, the ulema and the nobles, a dispute arose over who would sit where. Finally, to end the dispute, Badshah Salamat decided that the nobles would sit towards the east, the sayyids towards the west, ulema towards the south, and the sheikhs towards the north, and he would go to each of them himself to talk.