With translations from Bengal only beginning in the twenty-first century, dalit writings have remained largely unrepresented in the corpus of pan-Indian dalit Literature. Yet Bangla dalit literature has a long history: the songs of Sufis, Bauls, Fakirs and many other grass root religious mainstream Bengal, this was a robust and popular body of oral literature from the margins. The challenges and rebellions that characterize modern dalit literature are not unique to modernity, existing in the living tradtions.

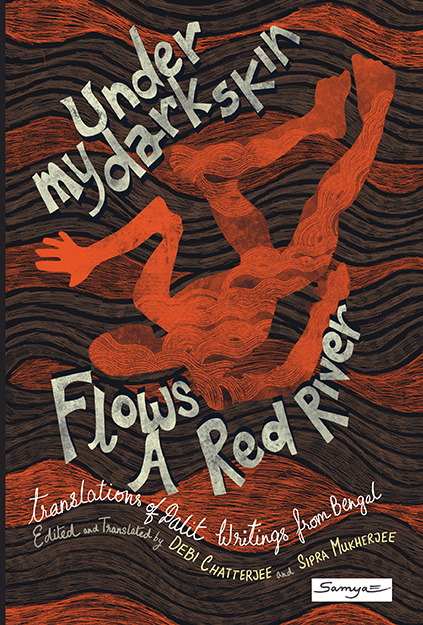

In the late twentieth century, dalits’ writings have been published by small publishers and little magazines, ushering a new vibrancy in Bangla literature. Edited and translated by Debi Chatterjee and Sipra Mukherjee, Under my Dark Skin Flows A Red River presents translations of a selection of essays, songs, poetry, short stories, extracts from autobiographies and novels as an introduction to a spirited and dynamic literature from Bengal.

The following are excerpts from the book.

From Introduction

— by Debi Chatterjee

Dalit literature unfolds through its association with the Dalit movement for social justice. It is today a powerful tool in the hands of Dalits in their struggle for human rights and assertion. This literature claims an identity that is distinct from mainstream literature. While Dalit writings have a long past, it is since the late 1960s and 1970s that there has been a surge as large numbers of Dalit writers have come forth to produce literary works of a varied nature. In West Bengal it took the form of a ‘movement’ since the 1990s. There were poems, short stories, novels, dramas, autobiographies and non-fiction writings, adding up to whatever could be retrieved from the past. Many of these works were published in the so-called little magazines, as mentioned earlier, which were themselves struggling for survival and identity. Over the decades their numbers have multiplied significantly and their presence distinctly asserted. Dalits, through their writings, have sought to address the concerns of real life: their pain, their sufferings and their dreams of freedom. Their portraits are presented against the wider canvas of social, economic and political developments. A large number of Dalit writers have come up from the Namasudra community who, having suffered not only from marginalisation due to social hierarchy but also as being a large section of the victims of the Partition. The refugees have struggled to make their way ahead, attained high levels of literacy, and used the pen to reveal their feelings, sufferings and aspirations. Others too have of course contributed towards the Dalit literary surge—they include, amongst others, members coming from the Rajbanshi, Poundra, Bauri and Malo communities.

It may be noted that the aesthetics of Dalit literature are clearly different from that of mainstream literature.[1] The yardsticks that may be used to assess the latter cannot be used for the former. It is not the beauty of language that is the criterion, rather it is the assertion in struggle that Dalit literature takes pride in. To understand it, it needs to be seen in the light of its social and historical setting, as essentially a tool of struggle, a cry for justice coming from the victims of structurally embedded, gross human rights violations; a major tool in their struggle for human rights.

[…]

From The Relevance of Dalit Literature and Its Evolution

— by Manju Bala, translated by Debi Chatterjee

Since 1954, the term ‘Dalit literature’ has been in moderate usage. Babasaheb Ambedkar was the founder of Dalit literature.[2] Focussing on him, Marathi poets created their poetry. Their long pent up feelings of anger, protest and the firm demand of liberation of Dalits were reflected in their writings. In a special issue of the literary magazine Asmitadarsh edited by Gangadhar Pantawane, the use of the term ‘Dalit literature’ drew the attention of the readers. There after there were many debates on Dalit literature, and as a result everyone became familiar with the term. In Bengal, the waves of Dalit literature arrived a little before the 1970s.

In 1992 the Bangla Dalit Sahitya Sanstha was born, supported by Manohar Mouli Biswas, Amar Biswas, Dr. Achintya Biswas, Pasupati Mahato, Swapan Biswas, Nakul Mallik, Manju Bala, Kalyani Thakur Charal, Dhurjati Naskar, Bimalendu Haldar, Jatin Bala, Kapil Krishna Thakur, Sukanta Mandal, Sunil Kumar Das, Samudra Biswas, Gopal Biswas, Pushpa Bairagya, Smritikana Haoladar and many others. It was decided that this organization would organize annual conferences on 24 and 25 December every year in different parts of West Bengal. Accordingly, the first annual conference was held at Vaina. The second at Hridaypur, then Malda, Murshidabad, Khannan, Madhabpur, Adra, and other places. Many Dalit writers and poets in association with the Dalit Sahitya Sanstha wrote with their hopes of liberation, determined to protest against their exploitation. People learn to live when they are able to overcome fear. The main lesson of traditional literature is that literature is the mirror of society; learning to understand society through the literature. But there is no effort to eliminate its evils. The nature of Dalit literature is somewhat different. In this literature, the writers are more concerned about documentation than the aesthetics. They do not emphasize what aesthetic value the literature has, or how beautiful the writing is. They simply project the picture of society. They speak of the joys and sorrows of Dalit people, that is, low-caste people, and such people become the main characters; those who never found a place of dignity in progressive literature.[3] The Dalit writers are busy trying to break out of the bondages of long years of marginalization. Through the writings of the poets their worldview comes out like the sharpened sword. And their ideas are warmed in the fire of consciousness.

[…]

Charyapada, an ancient literature, was in the most part created by low-caste people. In later times as the Aryans snatched education from them, they created literature orally and orally transmitted down the generations their feelings of sorrow and pain, words of happiness and many other feelings, through the medium of songs and rhymes.

Even though these were not written down, their feelings made them lively. In the songs of the common people there remains the touch of life. Actually, without the touch of the soil, literature cannot be created. It becomes mere art forms. And, whatever that aesthetic literature does, it cannot make any perfect assessment of the social picture. That literature is only the literature of entertainment.

And that literature cannot bring about any social revolution. Therefore, literature that is only for the entertainment of a few people cannot show the path to equality. So the common people have taken up the pen in their hands. But then, it is a fact that Dalit literature is not created simply with the taking up of the pen by Dalit people. There has to be a Dalit consciousness in their thoughts. That will never come out of the pen of the Dalits who are moulded by the brahminical line of thought. Those Dalit writers have written about Dalits merely for the purpose of creating art, not for registering any protest or condemnation regarding the life of indignity that Dalits have had to suffer for so long. No protesting voice becomes vocal through their writings. Rather, through their pen the propensity to make Dalit people accept their insults becomes evident. So they cannot become writers of Dalit literature. Simply writing about Dalits does not make for Dalit literature. It will become Dalit literature only when the Dalit writer finds in it his own identity. Even now many Dalit writers are creating literature along the brahminical line of thought. These are by no means Dalit literature. But then, no matter how much Dalit consciousness exists, the writings of non-Dalits will never become Dalit literature. Because in their writings there is the imprint of sympathy.

(First published in Chaturtha Biswer Chitralekha: Prabandha Sankalan, Chaturtha Duniya, Kolkata, 2017: 9-23. By courtesy.)

Notes:

1. For a detailed discussion on the aesthetics of Dalit literature see Sharankumar Limbale, Towards an Aesthetics of Dalit Literature: History, Controversies and Considerations, translated by Alok Mukherjee (New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2004).

2. There was a flowering of low-caste literature, both oral and written, in different parts of India long before Ambedkar’s writings. But the authorprobably refers to Ambedkar as the founder of Dalit literature in the sense in which such literature emerged from a very distinct Dalit identity consciousness that developed under the inspiration of the Ambedkar movement.

3. By progressive literature the writer probably includes all literature, other than Dalit literature, that has projected social change.