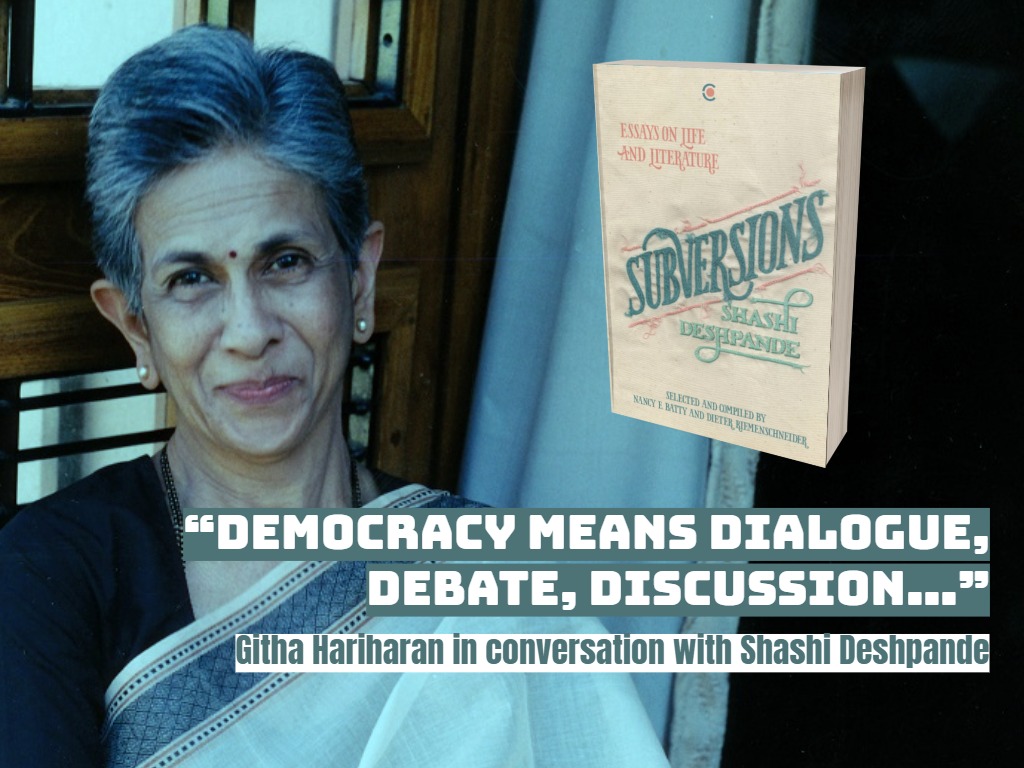

Shashi Deshpande has had a long and rich career as a writer of novels, short stories and essays. She has not only known many Indias, past and present, but also contributed to debates on the understanding of India’s contemporary social, literary, and political issues. Subversions: Essays on Life and Literature (Context, 2021), selected and compiled by Nancy E Batty and Dieter Riemenschneider, invites its readers to enter that fascinating dialogue.

In part one of a two-part conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, Deshpande talks about dissent, feminism and the role of a writer amidst the growing polarisation taking place in the country.

Githa Hariharan (GH): Your collection of essays, Subversions, which has just been published, has a powerful epigraph that seems perfect for the times. It quotes the indomitable Ruth Bader Ginsburg: “Some of my favourite opinions are dissenting opinions.” This choice of epigraph says a great deal about your aspirations as writer, woman, and citizen in search of democracy and freedom of speech. Shall we begin with the question most relevant for our times? What, for you, is dissent?

Shashi Deshpande (SD): Among the numerous judgements of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (RBG), many of which were on contentious matters, there is one judgement to which RBG and two other judges dissented. While the other two judges wrote the usual “I respectfully dissent,” RBG simply said “I dissent.” So the story goes. Perhaps she meant that there is no need to apologise for dissent, or qualify it. She must have believed that dissenters hope they are speaking not only for today, but also for tomorrow.

Dissent comes out of questions. The idea of dissent began, for me, with the personal, which is so often the case. My questions began when I moved from a free, unrestricted childhood to an adult world ruled by the idea that women have to live restricted lives. And so, the questions: Why was marriage so important for a girl that she and her parents had to subject themselves to humiliation from the family of the future groom? Why was a girl “given” in marriage? Why did they speak of a girl being “allowed” or “not allowed” to do something after marriage? Things have changed since then, though perhaps only for the privileged few. What has not changed is that a wife remains subordinate to her husband, and her life and personality are subsumed in her husband’s. I was pretty sure that mine would be a marriage of equality, that I would never be “the woman behind the man”.

To consider dissent as unpatriotic and anti-national is the beginning of the end of democracy.

When I began writing, things became clearer; writing always clarifies one’s ideas and thoughts. And the questions within me moved to the outside world. In fact, my first novel came out of Indira Gandhi’s policy of taking total control of her party and of the country. Soon, any dissent against her policies or views became almost lèse-majesté. Sycophancy, almost a hallmark of politics in our country, followed. But our brush with the idea of a Great Leader told us: If dissent is stifled, democracy is threatened.

We seem to have come once again to the same place. Intolerance of dissent has reached the stage where dissenters are called Naxalites, terrorists, unpatriotic and anti-national. I can remember a sick Girish Karnad sitting with a board round his neck which said, “I am an urban Naxalite!” A powerful image, and a new word coined for those who disagree with the powers that be. To consider dissent as unpatriotic and anti-national is the beginning of the end of democracy. Democracy means dialogue, debate, discussion. To stifle dissent is to take away the voice of the people. What despots want is a chorus of sycophants, not a healthy exchange of views and opinions.

“Sadly, dissent nowadays is considered unpatriotic and any criticism of those in uniform is stifled.” Surprisingly, these are not words spoken by an Indian about India, but by an American writer, who has been churning out legal thrillers for decades (John Grisham in The Rogue Lawyer). In fact, dissent is being stifled all over the world. What amazes me is that the governments in power don’t seem to realise a simple truth: When you deprive humans of something, it becomes even more valuable, it becomes something to be fought for.

One of the most alarming things in our times is the punishment given to dissenters. It not only punishes the dissenter; it instils fear into those who might have dissented otherwise.

We talk a great deal about the right to freedom of speech and expression. To me, the right to dissent is the other face of the freedom of speech and expression. I also consider dissent the agent of progress and change. If democracy means that the views of the majority prevail, nevertheless there is always a dissenting minority. And this can at times be more powerful than a dumb, unthinking accepting majority, ruled by slogans. A servile and subservient population guarantees a weakened democracy. After all, democracy does not mean that there is universal agreement. It only means that the majority view will prevail. This, after there have been debates and discussion about the issues. In a recent case, Supreme Court judge D Y Chandrachud spoke of dissent as the safety valve of democracy. A very apt comparison. For dissent which is suppressed can result in a violent explosion, while dissent expressed can lead to healthy debate and discussion. I also consider dissent not just a negative. It means positively standing by your beliefs. One of the most alarming things in our times is the punishment given to dissenters. It not only punishes the dissenter; it instils fear into those who might have dissented otherwise. It may make them think, “I better keep my mouth shut. I don’t want to get into trouble, or get my family and friends into trouble.”

GH: For those of us who have seen the women’s movement in different phases, in India and elsewhere, what does it mean to write texts informed by feminism? And what does it mean to live feminism day to day?

SD: It has been a very long journey for me, as I am sure it has been for many women, moving from a vague sense of dissatisfaction and inchoate thoughts, to confused ideas of something being wrong. And then, connecting it to the way women are regarded and treated before finally stumbling on feminism.

I first heard the word feminism in an American journal, The American Review (issue of 1973, it is still with me). There was a longish article in it, written by Isa Kapp about “the new feminism”. It began by saying, “…After more than a century of legal, social and cultural advances … the American woman is today in the throes of a new feminism more articulate, widely supported and militant than any in history.” I read this article not just with interest, but with a sense of release. Finally, I was hearing something that chimed with my own thoughts. Yet my own ideas of feminism did not come out of this “widely supported movement,” but out of what I saw around me: gross inequalities in every sphere of life between men and women, a subordinate status given to women in almost every field of life.

Also read | From Subversions: Essays on Life and Literature

It was the Mathura rape case that showed me the extent of injustice. It was a case in which a young Adivasi girl was held overnight in the police station and raped by two policemen. While the lower court and the High Court held it to be rape, the Supreme Court reversed their judgement. They concluded that since the girl showed no signs of struggle, and had no bruises, she must have consented; therefore it could not be rape. What I remember most vividly is the letter written by four law teachers to the Supreme Court (published in newspapers) arguing that the Supreme Court was mixing up submission and consent. They held that submission was natural when a young girl was in a police station in the middle of night, confronted by policemen who were figures of authority for her; she had no choice but to submit. That did not mean she consented. Therefore, it was rape.

This case woke me up to the injustice which women had to face, even from a judge. It also showed me, through the protests that followed, that this injustice could be questioned.

I was soon dubbed a feminist writer and my novels, whether for that reason or any other, never got their due as just novels; they were considered “women’s novels”, and, worse, “about women’s lives”. Which put them into an inferior pile.

Moving to Bangalore I found myself very peripherally involved with the work of an NGO working for women. One of their volunteers, who dealt with the victims of dowry deaths, told me that the suffering of the dying women was so terrible, she could not sleep for months. By this time I was seriously involved in my writing. But I knew even then, with just four novels written, that creative writing cannot bear the burden of an ideology, that no writer can write a story, a novel, or a poem to directly convey a message. To do so would mar the aesthetics of the work. And for writers, the aesthetics of creative writing is as important as the content. At best, the work can only be “informed”, as you rightly put it, by your ideas. I said openly in public that I was a feminist — this at a time when many women were chary of being associated with feminism, afraid of the backlash. I was soon dubbed a feminist writer and my novels, whether for that reason or any other, never got their due as just novels; they were considered “women’s novels”, and, worse, “about women’s lives”. Which put them into an inferior pile. It was hard indeed to see my work so denigrated. Years, no, decades later, I came across the words of Ursula le Guin: “There is no more subversive act than the act of writing from a woman’s experience using a woman’s judgement.”

Nothing could be more morale-boosting than these words, though I read them late in life, by which time I had been able to understand the value of my own work. Yet the denigration continued. Things are changing, very slowly, too slowly. I can only hope that the next generation of women will be able to break out of the tag of ‘woman writer’ and stand on a level field with all writers.

To live feminism day by day is just as hard as reconciling your feminist views with your writing. To live with feminism means a moral struggle within yourself. All of us live in a complex web of relationships which we nurture and depend on. To bring feminism into personal life could mean hurting a relationship. What do we do? Compromise on one’s ideology and save a relationship? Or forget one’s ideology? When it comes to children, especially very young children, there can never be any compromise with children’s needs. No ideology can stand against a child’s needs.

Also read | Listening to the Woman’s Voice: Githa Hariharan in conversation with Shashi Deshpande

What makes it hard to bring feminism in your day-to-day life, is the way feminism is looked at. I consider it one of the important movements of our times. Obviously, for it is a fight for equality by one half of the human race. But to the world, to the male world, and even to many women, it was and is a joke. Never has any movement been so derided and ridiculed as the feminist movement. Never has a movement been as misunderstood as the feminist movement has. Feminists are aggressive, they are man-haters, they don’t want children, they are trouble-makers — these are the perceptions, the prejudices. I know that I was the constant butt of a joke in the early days because of my views. Strength and affirmation came through books. And through the tireless and selfless work of activists, who are now thankfully getting some appreciation for the work they are doing. There is also some hope now, with the judiciary, especially the higher courts, taking serious note of any injustice against women, and with young people coming back into the fight. And more men (though still a pitifully small number), becoming sympathisers.

GH: What can we, as writers, do about making the powerful cliché “unity in diversity” live through our work? And what can we do, through what we write, or what we say in the public space, about the growing polarisation taking place in the country?

SD: The idea of India being a country where there was unity in diversity which had seemed so magical and meaningful after Independence, (and which had proved true during the freedom fight) today sounds both meaningless and irrelevant. Is it because we know it is unachievable? Have we given up on it knowing it is something impossible to achieve? Whatever the reason, it lies in our past, covered with dust and totally forgotten. The truth is that we have moved so far in our intolerance that we cannot bring back the idea of the underlying unity of this country. Religion has been revived, made a tool of dividing people. People are encouraged to be intolerant of “the other”, they have been manipulated into mistrusting one another, differences between them deliberately exaggerated. One would have to be extraordinarily optimistic to imagine that we can reverse the movement of the chariot which set off for Ayodhya thirty years back. That we can turn it back and make it go on a pilgrimage uniting the entire country.

But change will come, changes have to come. The wheel of fortune never rests, it keeps turning.

The truth is that we have moved so far in our intolerance that we cannot bring back the idea of the underlying unity of this country.

As far as writers making the cliché live is concerned, I am afraid I am not sanguine. Writers can do very little. People have been brainwashed into accepting a divisive ideology. The times when writers could influence people are way behind us. Religion has got such a grip over the country, that rational thinking and understanding have no place in a person’s thinking. Besides, writers no longer have that larger-than-life image which made people look up to them. There are too many influences working on people now, too many voices speaking. The writer’s voice is lost in this cacophony. Politicians and the entertainment industry, both replete with money, have poisoned the wells of culture. We who write in English are even more impotent. English writing reaches a small minority and despite the fears of English threatening our languages, these languages are what reach most of the people. They have a kind of power and influence which English lacks. I do believe that a number of factors have to come together to make a real impact on the thinking of a people. A very small part of this will be the contribution of those who write in English. One has to comfort oneself with that thought.