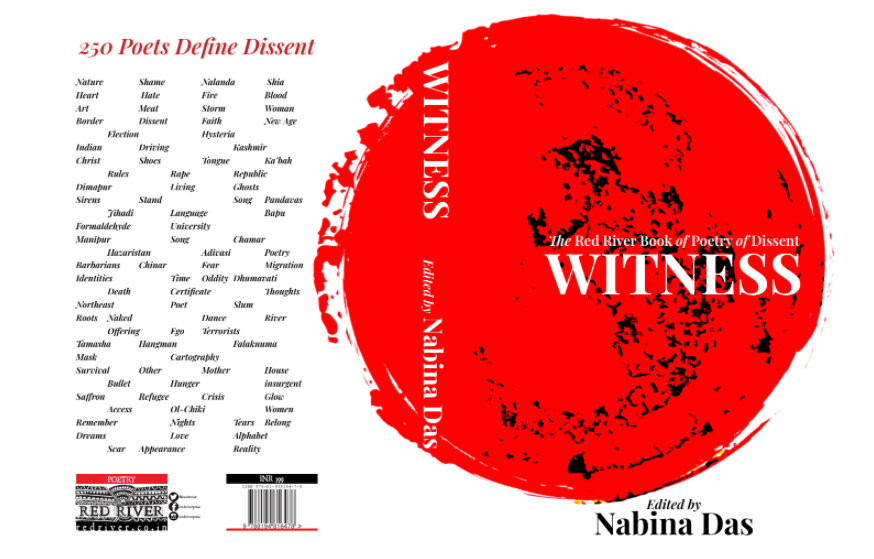

Edited by Nabina Das and published by Red River, Witness: The Red River Book of the Poetry of Dissent collects 250 poets who define the meaning of “dissent”, writing from a gamut of experiences and sensibilities — most undoubtedly first-hand, first and foremost, and also several as reactions and responses.

The following are excerpts from the book.

Introduction

– by Nirupama Dutt

Chop off every tongue if you may

the words have been uttered…

Words reach out with a rare rage, urgency, indignation, and angst as poets turn witness to dissent across the length and breadth of the sub-continent in contemporary poetry in this colossal anthology containing 250 poets. Penned in different languages and touching a wide range of subjects, words rise out of the despair to mark a dissent with the scheme of things.

These words are not mere words but the anguish and despair of a people with whom poetic dissent has been a way of life for thousands of years. The rhythms of doubt, debate, and resistance date back to the Vedic times, move onto the medieval times, and are prominently present even now when the popular perception of the poet as the witness is reaffirmed in no uncertain terms.

Amid the vast array of poems from different nooks and corners of the country, those declared and other undeclared disturbed areas, from the Brahmaputra in the Northeast to the Liddel River steaming forth through the Kashmir highlands, this book showcases striking voices that arrest the ears. From the lilt of the Adivasi tea-garden dialect of Assam, to Dehwali Bhili, Santhali, Kokborok, and several Indian languages rendered in English, as well as Englishes from diverse poets, this anthology captures the essence of many registers in India. The strident tones and images draw the attention of the complacent middle class and the privileged as a reminder of what tragedies have been wreaked by the enablers upon the people of the land.

Whether it is the cries of starving children, or digital blockades of a people calling for azaadi, bullets to the head and heart, blood stains and tears, women battered and erased, or choices of love and food, the poets turn witness to the times in this vast collection to the events that have been unfolding before us day after day on themes related to oppression. Be it religion, gender, caste, creed, mental health, diversity, as well as pride and prejudice of all kinds that enveloped the sub-continent like never before in recent times, the poets in this collection have come together like never before, their voices united. While some of the major names of contemporary poetry grace this anthology, there are several new and emerging names from different parts of the country — new poets who usually are swept away by the tide of hegemony even in literary arenas — who have had the courage of standing witness to the atrocities of the times. Poet Parul Khakhar’s ‘Shav Vahini Ganga’ (Ganga the Flowing Hearse) which we read when this book was already completed, resonated with our inner cry of O Ganga tumi, Ganga boichho keno (O Ganga why do you flow on). Memory indeed fights forgetting in Witness by Red River through poetic testimonies, exactly as poet-anthologist Carolyn Forché had compiled in her anthology, on which Nelson Mandela showered these pertinent words: ‘Poetry cannot block a bullet or still a sjambok, but it can bear witness to brutality—thereby cultivating a flower in a graveyard.’

Appreciation to poet-anthologist Nabina Das for taking on a gigantic endeavour of carrying on the poetry of witness to the 21st century and choosing the home soil for planting flowers in the graveyards at a time when these were most needed. Besides the poetry being written in English, an effort has also been made to include translations from different languages. Spoken word and performance poetry too is included, and the volume makes for a pan-Indian perspective of standing against oppression and establishing the role of the poets as those who will speak out no matter what the norms of the times be, and translate human pain in words. The poems become a window into looking straight in the eye at all that was unsavoury and inhuman. They do not entertain denying that wrongs did not happen, or worse still, upholding the fault-lines as something that was inevitable. Dibyajyoti Sarma, the publisher of Red River, has shown tremendous foresight in bringing to the readers a precious document of the poetics of protest, an absolute need for our times.

This collection of poetry that reaffirms the courage to confront oppression, also reaffirms the correct meaning of words, their searing power. This is what the Dalit revolutionary poet of Punjab, Lal Singh Dil meant when he said: Words have been uttered long before us and long after/ Chop off every tongue if you may/ but the words have been uttered…

[…]

We Surrender

– Dibyajyoti Sarma

Have it your way, and release me from

this accursed body which defiles the land,

and with your help I will meet your gods and

ask why they made me a scum and you the king

You, the beloved of gods, who is better than

other men, you, who wields the sword and

pronounce justice, rules that benefit your kind,

to dominate and lord over men and beast

You, who wouldn’t oppose a Brahmin, but would

accuse me of crime, you, the Purusottam, who is

my master, and I am but your feet and you are

my powerful arms who would rebuild my shape

You, who blame me for a death, not your irrational

gods, who if upset, should have struck me down,

not a child I would not be allowed to touch, and

not my child for whom I could not blame you

You, who did not come to the aid of this grieving

father, who did not consider us when his kingdom

swallowed our village in the hills, when I lost my

son to the cold and my wife to a royal guard

Have it your way, and I accept you beheading me,

for, I would leave this wretched earth where I am

less than a man, and would find another where

you are no better than me, and I am no worse

Shambhuk, a shudra, is found to be performing a penance in the forest, a forbidden act, and a Brahmin couple alleges that their son died because of Shambhuk’s penance. The righteous king must take action, and decapitation is the only punishment.

[…]

The Republic’s Demise

– Rohinton Daruwalla

Rumours of the republic’s demise

were spotted late last night

close to Churchgate station,

heading towards Marine Drive,

filling potholes with little spoors

of dissatisfaction.

Their unclean fur was said to be

thickly matted with the dirt

of treason, and the poison dripping

from their fangs left little holes

of doubt on the sidewalk

outside the Ambassador.

No processions were hobbled,

and no statues injured as they

crossed unmixed signals and

ran along the old wet wall

of young lovers, and only

a single glass of lukewarm

chai was shattered, as they

tripped into an entirely

voluntary drowning.

Their scampering claws are said

to have damaged zero tetrapods

(two of which were, however,

nicked by a few patriotic bullets).

The rising water at your feet

is reported to not contain

the stink of revolution,

just the surfacing truth

of long uncleaned gutters.

Also watch Soibam Haripriya read her poem from the collection.