A late-night phone call from his ex-girlfriend Anasuya forces writer Arjun Kumar to leave his wife and home in Delhi and travel to the mofussil town of Noma on the UP-Bihar border. The reason — Anasuya’s husband, Rafique Neel, a college professor and theatre director, has mysteriously disappeared.

Soon after he arrives, Arjun realises that things are not as they seem: the police are refusing to register a missing-persons case, Rafique’s student Janaki has also disappeared, and the locals are determined to turn it into a case of ‘love jihad’. And when Arjun begins to dig deeper, what he finds endangers him and everyone around him.

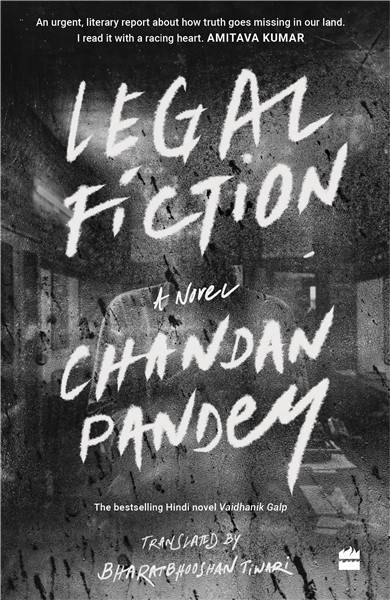

Inspired by true events from today’s India, Chandan Pandey’s Vaidhanik Galp has been translated into English by Bharatbhooshan Tiwari.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

From what Anasuya had said, I thought there would be more people. But as I walked into the station once more, I saw that there were only four, including her. They stood facing the police station as if it was a temple, with a sense of supplication. Two constables blocked their path at the threshold. One stood with his back against a pillar, head turned up towards the skies and eyes closed. The other sat on the threshold, the folds in his neck shifting as he looked at them in turn. He kept saying he was listening to them, but he was the only one speaking. His legs were spread wide, and he had pressed his lathi – a well-oiled, gleaming bamboo stick, I should add – into the ground between them, as if he wanted to drill to the centre of the earth.

The three men accompanying Anasuya could easily be identified, not just because they were young, but also because they looked agitated. Anasuya had a hand on her hip, as if it was the only way she was able to stand. She wore a faded green salwar-suit with a turquoise dupatta folded twice and meticulously draped around herself.

I was watching this as I came forward. Then something happened that I would never have believed had it not occurred right in front of me.

Let me first address the matter of belief. Why wouldn’t I have believed it? Was it because, despite being a writer, I believed in systems and organizations more than in human beings? Or was it because I had so far been spared by this organization known as the police? Why?

That ruffian, sorry, that constable who sat on the threshold, picked up his lathi and poked its lower end, which had some mud stuck to it, against Anasuya’s belly. Twisting it hard, he asked menacingly, ‘How far along?”

All three young men shouted at once, and the two constables were perhaps just waiting for the chance. The thuds of the lathis began to drown out the cacophony of abuses. But what was truly heart-wrenching were the screams that rang out between the blows. Were there two criminals and three human beings, or two policemen and three criminals? How could I watch this? How was the world watching it?

I ran towards the commotion. Sahadeo raced ahead of me, and some others too. But they stopped at a little distance. If I say that the constables stopped beating them because we ran towards the men, it would not just be a lie but also an act of ingratitude. But they stopped. Sahadeo went over to the students while I went to Anasuya. Several others watched her with such timid helplessness, as if they would have done anything for her, if only they could. When I saw that there were a few women among the crowd who would take care of her, I left her side and walked up to the constables.

I tried to remember where else I had witnessed a scene similar to the one I had just seen – of the constable pushing his lathi into Anasuya’s belly. But in that terrifying moment, I couldn’t remember where. I did not know how to talk to the police. I did not even know how to address them. The idea of giving them respect and calling them ‘sir’ was abhorrent. If I said, ‘Good morning,’ they would know I was an outsider. So, I simply joined my hands and said, ‘Namaskar.’

The two sat on the threshold, panting. When they saw me, one of them said, ‘Bark.’a ‘Ji, namaskar. My name is Arjun. I am her husband’s friend.’

The act of uttering this sentence alone drenched me in sweat. If there was a mirror in front of me, I would have seen the drops pop out on my forehead. But there was only the grimy wall of the law, and all I could see was fear. In that mirror of fear, all I could see was Anasuya sitting on the ground with her legs splayed out. As for myself, I just felt like I had been shoved into a deep well from the mountain peak that was Delhi. ‘Ji, I am her husband’s friend. I’ve come from Delhi.’

Perhaps it would have been better not to mention Delhi, but it would have inevitably come up sooner or later. Nonetheless, they must have felt I was trying to throw my weight around by bringing up my big-city background right at the beginning. If they didn’t panic, it was well and good. But if they did, they could have hurt us all. So, I changed the topic and reconciled myself to addressing the two criminals as ‘sir’.

‘Sir, I am Rafique’s friend.’

‘Will you say something else?’ The two spoke up at once. ‘Sir, he hasn’t come home for three days.’

‘Are you his lawyer?’

‘Not at all, sir. I am just a friend. I come from Delhi, where I work for a publishing house.’ I tried to keep the mood light, but I didn’t know how long I could continue with this.

‘Are you a writer?’ a third constable who sat a little apart asked, almost shouting out his question. I was so focused on the first two, I wouldn’t even have realized he was present had he not interrupted. This would have been extremely difficult to answer, but fortunately one of the policemen at the threshold asked, ‘Which newspaper?’

I calmly responded, ‘Sir, Niyamgiri is a publishing house. It also has a post called “editor”, which is more like that of a clerk and nowhere near as powerful as that of a newspaper editor. I am an editor with Niyamgiri.’

I was astonished. What had happened to my self confidence? What about me being a writer? Where did my faith in the power of words go? Why was I afraid? And if I was afraid, then why was that fear spreading through my words?

The third constable walked up to us, taking his time to climb down the two steps just so he could smile.

‘Daroga Babu will come sometime between 3.30 and 5. A Union minister is visiting in a few days and we have to make preparations. Most of us at the station are busy with that. Come back in the afternoon. The matter can be registered only then. Explain this to your friend’s family as well.’ He came right up to me as he said this.

His words came as a relief. I was so glad to get over my agony that I told them I would come back in the afternoon and helped the students get up. Those who saw me may have thought I was helping them because the beating had broken them. But the reality was something else. I couldn’t understand how I would face Anasuya. We were meeting each other after eleven or twelve years. And I still couldn’t make up my mind whether to continue carrying the ghosts of our past, or to start anew, like a friend who had come to provide her succour in her time of trouble. Or should I be like a stranger, trying superficially to soothe her pain? These questions slammed me over and over as if I was stuck inside a broken lift.

I stopped thinking about all this because I still needed to look after Anasuya. I turned around. She sat so still, even a stone could have taken lessons from her. I remembered her eyes, but at this moment they were brimming, like an ocean that one cannot fathom or even gaze into. When she closed her eyes, copious tears streamed out. When she opened them, the teardrops hung from her eyelashes the way raindrops hang from a clothesline. She continued to blink hard, as if she couldn’t decide whether to keep her eyes open or closed. There was no third option, after all.

Two women helped her up before I could reach her. They too must have come to the station because of some compulsion. I gestured to one of them to step aside and held Anasuya’s arm. That’s when Anasuya looked at me, and I looked at her looking at me. It must not have been more than a few moments, and god knows what she saw, but what I saw was a cobweb of bygone memories. Sahadeo rushed to the car. Anasuya gestured as if to tell me she didn’t need assistance. I was relieved she didn’t push me away. I let go of her arm but motioned to the woman walking by her side to carry on.

I thought I must speak to the constables once more. If they agreed to register an FIR for a bribe, I should pay them. But what if they got riled by my offer? Policemen do not refuse a bribe, I was sure. Why would anyone think otherwise? But if the act of bribing them brought with it the risk of them getting caught, it would aggravate them. When I turned around, I found the third constable standing right in front of me. The two of us were not even a metre apart. If I were a child, I would have wet my pants. He shot off, ‘Are you a writer?’

A black badge on the right of his uniform announced his name: ‘Brijnandan’.

I replied, ‘What are you saying, sir?’ What else could I have said? He asked once more, his voice insistent this time. ‘Are you?’

I was aware of the pitfalls of such a situation. If the police sensed they needed to be careful about something, it would hurt the matter of Rafique’s investigation one way or another. For this reason, and since I had not written for a while, I simply said: ‘No.’