The Last Prince of Bengal tells the true story of the Nawab Nazim–whose kingdom ranged from the soaring Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal–and his family as they sought by turns to befriend, settle in and eventually escape Britain.

From glamourous receptions with Queen Victoria to a scandalous Muslim marriage with an English chambermaid; and from Bengal tiger hunts to sheep farming in the harsh Australian outback, Lyn Innes recounts her ancestors’ extraordinary journey from royalty to relative anonymity.

The following are excerpts from the book.

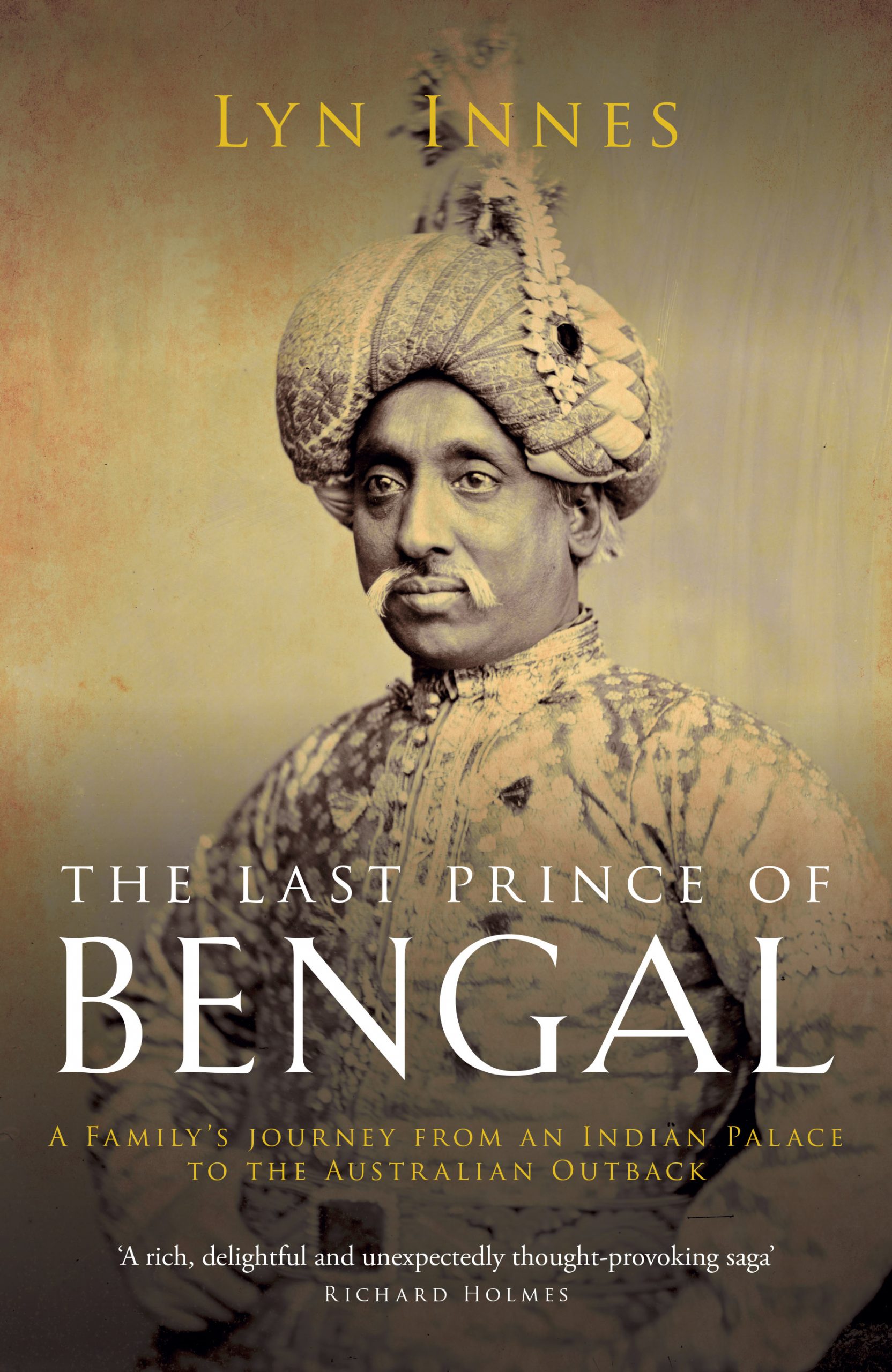

A hot summer day in February 1945, a few weeks after my fifth birthday. We had just moved from the slab hut near the road to our new fibreboard house on the hill, and I was watching my mother unpack. At the bottom of a trunk, wrapped in tissue paper, were several old photographs mounted on card. Looking straight out towards the camera in one were my father’s Scottish parents: my grandmother in a high-necked long-sleeved dress, my grandfather in a tightly buttoned suit. There was another photograph of a man in profile – an elegant man with a fine, waxed moustache, prominent nose and broad forehead. In the sepia print he is only slightly darker than my Scottish grandparents.

This, my mother told me, was her father. He was Indian – no, not an American Indian but from India – and he was the man who had painted one of the two oil landscapes that hung in our freshly decorated living room. His painting is unobtrusive: a small, black-framed pastoral scene depicting a field with dark green trees, six inches by nine inches. The colours are sombre. There is no sunlight. Growing up I had assumed that the field was English since it did not look Australian. Examining the picture more closely now as it sits above the desk in my study in Kent, I see that the frame is not black but brown, that the trees in the foreground are a pine and an oak or chestnut, that there are brown cows in the field, and there is a suggestion of a ruined tower in the distance. The scene could be English or French.

This painting is the only thing my mother inherited from her father – or at least the only thing she had kept. He had died four years previously, just before my first birthday. To me then and now this quiet and unmistakably European rural scene evokes a distinctive and intriguing aspect of my grandfather’s character: somehow, his Indian identity had to include being a painter of European landscapes. My mother later told me that her parents had lived in the suburb of Saint-Cloud, Paris, for several years; that her father had studied art there; and that his work had been exhibited in Paris. Once, she recalled, her parents had visited the Paris zoo, and on recognising an elephant as one that he had known as a boy in India, her father had called it by name and commanded it to kneel, which it did. She told one other story about my grandfather. When he was young, he and his older brother had caused outrage amongst the Hindu community in their neighbourhood by tying firecrackers to the tail of a cow and setting light to them. Their Muslim father had had to pay a large sum of money in compensation. It was a story my mother repeated several times in later life without, as far as I could tell, any concern for the cow.

[…]

The twenty-sixth of January 1991 marked my first visit to India, and my fifty-first birthday. Having checked in to my hotel in Delhi, I decided to celebrate this double event by ordering a cold beer, only to learn that no alcohol could be served that day because it was India Republic Day. That my birthday fell on both Australia Day and India Republic Day seemed wonderfully serendipitous, an endorsement of my own composite identity.

The television in my hotel room showed the commencement of the Republic Day parade and, since the hotel was not far from Connaught Square, where crowds were gathering to watch, I made my way there. Dazed by jet lag, the crowds of people, the noise, the dust, I hesitated near a group of men, only to be hastily ushered by marshals towards the women and children seated on the ground. There was, I now realised, a clear gap of about three yards between the standing men and the seated women. A group of women smiled and beckoned to me to join them on the rug they had spread out; gratefully but less gracefully I sat with them, exchanging halting snatches of English conversation. The children looked at me curiously; one small girl approached and placed her brown arm against my pale pink one, and laughed at the strangeness of the contrast and her own daring. In an odd way that encounter seemed almost a mirror image of my first experience of colour prejudice in that school bus in Australia, but this time the child’s discovery of colour difference brought fascination and delight.

Some years later I finally visited Murshidabad, together with my friend and colleague Professor Bala Kothandaraman. We hired a guide to show us the sights, ending with a visit to the Hazarduari Palace. There it was, the palace of a thousand doors, an imposing building similar in style to the National Gallery in London. We passed rooms full of guns and swords, a stuffed crocodile with gaping mouth, a cabinet displaying a plate that changed colour if the food on it was poisoned, the durbar hall with a silver throne and a huge chandelier gifted by Queen Victoria, a library filled with leather bound volumes by Aristotle, Gibbon and Scott. The library also displayed a magnificent thirteenth-century Qu’ran that had once belonged to the Caliph of Baghdad. And then we came to a gallery with a great row of ancestral portraits. Among them were two life-size portraits of my great-grandfather as a young man, one showing him standing regally in red robes, the other seated more casually and dressed in white silk. He looked remarkably handsome and elegant.

Bala, who was perhaps even more excited than I was about my Indian ancestry, told our guide about my relationship to the Nawabs of Bengal. A long discussion in Hindi ensued. ‘I know your people!’ the guide then exclaimed in English. ‘Would you like to meet them?’ I hesitated, not at all sure that ‘my people’ would welcome such a meeting, but Bala was determined that it should happen. And so the guide took us to the house of the ‘chote nawab’ (the young nawab) Syed Reza Ali Meerza, who claimed direct descent from Mir Jafar. His resemblance to my mother was what first impressed me – although her skin was paler, I saw the same narrow face and high cheekbones, the same prominent nose and ears, even the same air of peering into the distance when speaking. I was made very welcome, invited into the house for tea, and shown photographs of other relatives. On parting, Bala asked him, ‘So what is your relationship to Lyn?’

Syed Reza Ali Meerza took my hand. ‘She is my sister,’ he said.

The distance between myself and my Indian ancestors had suddenly narrowed. With a new sense of entitlement I returned to London to research the first chapter of their story, which would also become the story of my grandparents and parents, their journeys and mine.