![]()

How did cinema enhance Gandhi’s impact on the ordinary Indian? Let’s consider four films – Kurmavatara (Kannada) (2011) by Girish Kasavalli, Babar Naam Gandhiji (2015), a Bengali feature film that marked the debut of Pavel, The Salt Stories (2007) a documentary by Lalit Vacchani and Ananth Narayan Mahadevan’s Gour Hari Dastaan – The Freedom File (2015) – which offer original and unique insights into the impact of Gandhi on the life of an ordinary man. Though not a visible presence as a character, ghost or even a ‘voice; in any, yet Gandhi’s presence is resurrected from history in these films by employing both fact and fiction.

Kumravatara (2011)

![]() A still from Kurmavatara

A still from Kurmavatara

In Hindu mythology, kurma, which means turtle, is the second avatar of Lord Vishnu(variously represented by ten avatars). Like the other avatars, Kurma is said to appear in times of crisis to restore the equilibrium of the cosmos. His iconography is either that of a tortoise or, more commonly, as half-human-half-tortoise. These figures are found in many Vaishnava temple ceilings or wall reliefs. The story of Kasaravalli’s film Kurmavatara takes seed of this mythological legend and produces it through the lens of a contemporary character and the changes that happen in his life. The film is based on a short story of the same name by Kannada poet and writer, Kum. Veerabhadrappa.

The story revolves around Rao, a government employee, and ageing widower, living with his son, daughter-in-law and grandson, who owing to his strong resemblance to Mahatma Gandhi, is picked up by a television producer to portray Gandhi’s role in a television serial. Rao resists the offer initially because neither had he acted before in his life nor was he a Gandhian; but is forced to accept the assignment by his son and daughter-in-law to help their son get admission in a good school. However, after having reluctantly agreed, he pours himself wholeheartedly into the character. His work in the serial makes him famous instantly. Fans begin crowding his home and the lifestyle of the lower-middle-class family improves drastically as the son and daughter-in-law cash-in on his new-found fame.

However, the most dramatic change occurs in Rao’s character as he begins reading on Gandhi and his ideology for a role he had never dreamt of performing. The serial turns his life around, as he starts examining his life and philosophy. As the fans keep growing, the humble Rao has to come to terms with the fact that simply ‘portraying’ Gandhi does not “make” him a modern-day Gandhi. The serial, thus, transforms his life into a journey that enriches him as an individual with a new perspective on life, family, and relationships.

Dr Shikaripura Krishnamurthy who played Rao, an ordinary man, who is asked overnight to step into the mighty feet of Mahatma Gandhi for the small screen, gave an outstanding performance – bereft of glamour or chutzpah, investing the character-within-the-serial with as much sincerity and authenticity as possible. A moving sub-plot explores this man’s warm and humane interaction with Kasturba(played by famous Kannada actor, Jayanthi) within the serial, and off the sets. The sub-plot shows Jayanthi empathising with the predicament of her co-actor who suddenly finds himself famous overnight owing to his portrayal of Gandhi, and endeavours to befriend him not as an actress or even a co-actor, but as a fellow human being.

The film is enriched by Kasaravalli’s signature low-key handling – no pomp and show, loud colours or music, but extremely realistic and natural performances by the entire cast. Kurmavatara was screened in 17 film festivals and won acclaim at Bangkok, New York and Vancouver. It won the Feature Film Award for the Best Kannada Film at the 59th National Film Awards. The cinematography is low-key and appears as if most of it is shot in natural light. Gandhi does not appear in the film but we discover him through the metamorphosis in Rao who portrays him for a short while but changes forever.

About his statement, Kasaravalli says, “It is a question of whether Gandhian values can lift our present world from degeneration. Today, we are moving in the opposite direction. Gandhi believed in small things. Nowadays, we believe only in big things. Even if you are telling a lie, you only want to sell your product.”

The Salt Stories (Documentary) (2007)

The Salt Stories (2015)

The Salt Stories (2015)

Nearly eight decades after the Dandi March, filmmaker Lalit Vachani made The Salt Stories, an interesting documentary raising questions about the contemporary relevance of the Salt March. Set in modern India, The Salt Stories is an 84-minute documentary, presented as a road movie that follows the trail of Mahatma Gandhi’s salt march of 1930. The film puts the historic Dandi March into perspective by juxtaposing it against the reality of the poor being denied freedom by depriving them of basic needs like food, clothing and shelter. Has Gandhi’s non-violent means to attain a political end for the benefit of the entire country really brought freedom to their descendants, the poor and the oppressed? Or, has the Dandi March been reduced to a token for non-violence to be relegated to history textbooks? – are some questions the film seeks to ask.

The film introduces the viewers to Mohammed Bhai, standing in, what remains of his bangle factory, where the number of workers has dwindled to a handful after his machines and workshop were destroyed by Hindu fundamentalists during the riots. The team then sets off on a road journey to Dandi passing through rickety roads and small towns, talking to people on the way to find out if they knew who Gandhi was, or about the Dandi March.

One of the people we meet on the journey is, Ketanbhai, Dalit leader of Navagam village, who was forced to resign as upper- caste members refused to let him go on. 102-year-old Gordhanbhai Bakhta, the sole living survivor of the Dandi March, who passed away soon after, is also seen recalling and sharing his experiences.

Explaining his motivation, Vachani says, “In 2002, I was completing The Men in the Tree. It revisits the RSS and Hindu fundamentalism when the Gujarat massacre happened. I was horrified and shocked. How could this happen in Gandhi’s Gujarat? On the other hand, I surmised that this could happen only in Gujarat. This is one state where the ideology of Gandhi has been completely erased. The Men in the Tree explores RSS’ attitude to Gandhi. I tried to show how the RSS denigrates and neutralizes Gandhi and his ideology, yet appropriates him when they feel he is convenient for the Hindu right. This is what motivated me to revisit the Salt March trail and find out how things are.”

Set against the backdrop of Gandhi’s original journey, this road-movie makes caustic comments through its telling visuals and one-to-one interviews, on how the globalization of Gujarat equates Gandhi’s ‘salt’ to a metaphor on poverty, forced migration, joblessness and injustice. Secularism, as the film points out, is conspicuous by its absence. The film meanders through time and space – juxtaposing the present scenario, shot in colour, with the past, compiled with silent Black-and-White archival footage (courtesy: Gandhi Films Foundation in Mumbai). Such a presentation lends the film a unique stage to place a sense of history, time, place, people and events in perspective, while at the same time pitting old and new values against each other to provide an objective view of how relevant the Salt March is in today’s India.

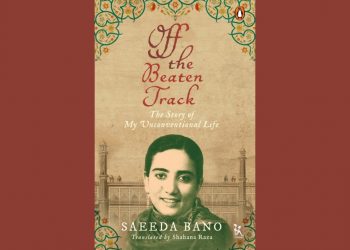

Gour Hari Dastaan – The Freedom File (2015)

Gour Hari Dastaan – the Freedom File: Movie poster

Gour Hari Dastaan – the Freedom File: Movie poster

Among films inspired by or based on the honesty and integrity of Gandhi is, Gour Hari Dastaan – The Freedom File, a biopic on Gour Hari Das, a Gandhian, living in his eighties. Actor-director-scriptwriter Ananth Narayan Mahadevan decided to make this film on the struggles of this Gandhian whom he had met and interacted with and whom he confesses to having been enriched by as a human being. In the film’s title, Gour Hari Dastaan – The Freedom File, the surname has been extended from Das to Dastaan which means “story.”

During his teenage years, Gour Hari Das actively participated in the struggle for independence in Balasore, Orissa where he was growing up. He was enrolled in Gandhi’s vanar sena for younger freedom fighters. His job was to courier messages and letters between freedom fighters by running alongside rushing trains to hand over the letters. When he was 14, he was arrested and imprisoned for three months. “I read about Gour Hari Das in a tabloid. The headline screamed, “It took him 32 years to prove that he is a freedom fighter”. The irony was there for everyone to see. I probed further and tracked him down in a distant suburb of Mumbai…Dahisar,” says Ananth Narayan Mahadevan who directed the film and also co-produced it along with Bindiya and Sachin Khanolkar.

His story became interesting after an episode, around mid-seventies, when one day his son complained that he was refused admission under the freedom fighter’s ward’s quota as he could not produce proof that his father was a freedom fighter. It was then that it dawned on Gour Hari Das that he had not received the Tamra Patra which every freedom fighter is entitled to, as he had not really fought for any award. He was left speechless with shock when his son turned around and asked him, “Were you really a freedom fighter?” At that moment something ticked inside him and his fight for another ‘freedom’ began. He embarks on a journey to find proof that he was indeed, jailed for three months, that he really was a freedom fighter, that he was a genuine member of Gandhiji’s vanar sena and that he was a true Gandhian who did not believe in rewards for fighting for his country’s freedom.

Das wanted to get his own proof. It took 32 long years for him to be finally given the Tamra Patra – now by the Maharashtra CM himself. In his struggle, as the director, informs us, Das knocked on 321 doors, wrote 1043 letters to different officials, climbed 66000 steps, and pleaded 2300 times in Post-Independent India to prove that he was the freedom fighter who was once blessed by Mahatma Gandhi and even jailed for fighting against the British. During this turbulent journey, he visited government offices, influential politicians, ministers, media, jail officials and so on and was called ‘fraud’, ‘thief’, ‘crazy’, ‘eccentric’ by others. The struggle cost him 32 years of his life to get what he feels was justice.

Vinay Pathak, a gifted and trained Bollywood actor, who was chosen to play the title role says, “In 2008, Gour Hari Das was front page news. The Maharashtra Government had just conferred the freedom fighter certificate to him. I remember reading the article and I was amazed by it and later when Ananth asked me to play him. It was an author-backed role no actor would let go of.”

The film revolves around Gour Hari Das. He is like a solid tree from which the branches of interesting characters emerge to add to his story. There are fictional interpolations to detail the struggle of Gour Hari Das and a fictionalised climax which ends the film. But these factors do not take away from the core message of the film – that the honesty Gandhi upheld endures albeit among a handful of Indians, for whom his teachings mould their entire life.

Babar Naam Gandhiji (2015)

Babar Naam Gandhiji

Babar Naam Gandhiji

In Babar Naam Gandhiji, Gandhi assumes the form of a biological father, – for a street urchin named Kencho (snail) who was discarded in a dustbin by an old alcoholic and grew up in the dredges of Kolkata – after a policeman jokes about Gandhi being his biological father by showing him a currency note with Gandhi’s face printed on it. Kencho takes this seriously and his life changes forever.

“The story is not mine, it is Kencho’s story,” says the voice-over of Pavel (Parambrato Chatterjee) who runs an NGO for street children who attend his classes only because he arranges tiffin for them. Kencho is their leader, who not only uses his intelligence and shrewdness to fool people to part with their money but also teaches clever ways of extortion to other kids. He hardly attends Pavel’s classes but uses this young man as his bank. “I have faith in you,” this worldly-wise ten-year-old tells him.

Kencho is a friendly chap and enjoys the support of all the fellow beggars in the locality, though a couple of goons bash him up black and blue when he refuses to part with their demand for hafta. Yet even these goons rally behind him when he decides to join the big school in the neighbourhood in response to a teacher who insults him in his father’s (Gandhi) name!

The entire group of beggars take out a procession with their indigenous band, in support of Kenchu as he nervously marches towards the big school for his final interview. In fact, his first instalment fee is put together by a medley of street men, women and children who have saved from the “weekly” hafta; even the goons surrender their hafta to contribute to the target sum of Rs. 5000. And what does Kencho do? He upturns a sack of small coins in the principal’s cabin with the promise that “more will come when needed” from the same source. The smooth falsification of every single document needed for his admission test from birth certificate to ration card to age proof to the name of his father written in full as “Kenchodas Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi” and many more such small bits and pieces picked up from real life are portrayed on celluloid. These make Babar Naam Gandhi a film worth watching!

The life-changing story of Kencho is based on a string of lies, dishonest and corrupt practices – by individuals and institutions, including the police and high-nosed gentlemen, which are in fact, diametrically opposite to the Gandhian ideal of honesty and integrity. But for Kencho, these lies lead to a decent future and an honest way of life – and perhaps this is where the strength of the film lies.

Read more:

The Self-Reflexive Cinema of Rituparno Ghosh

The Muslim in Hindi Cinema

Kaagaz ke Phool: 59 Years Later