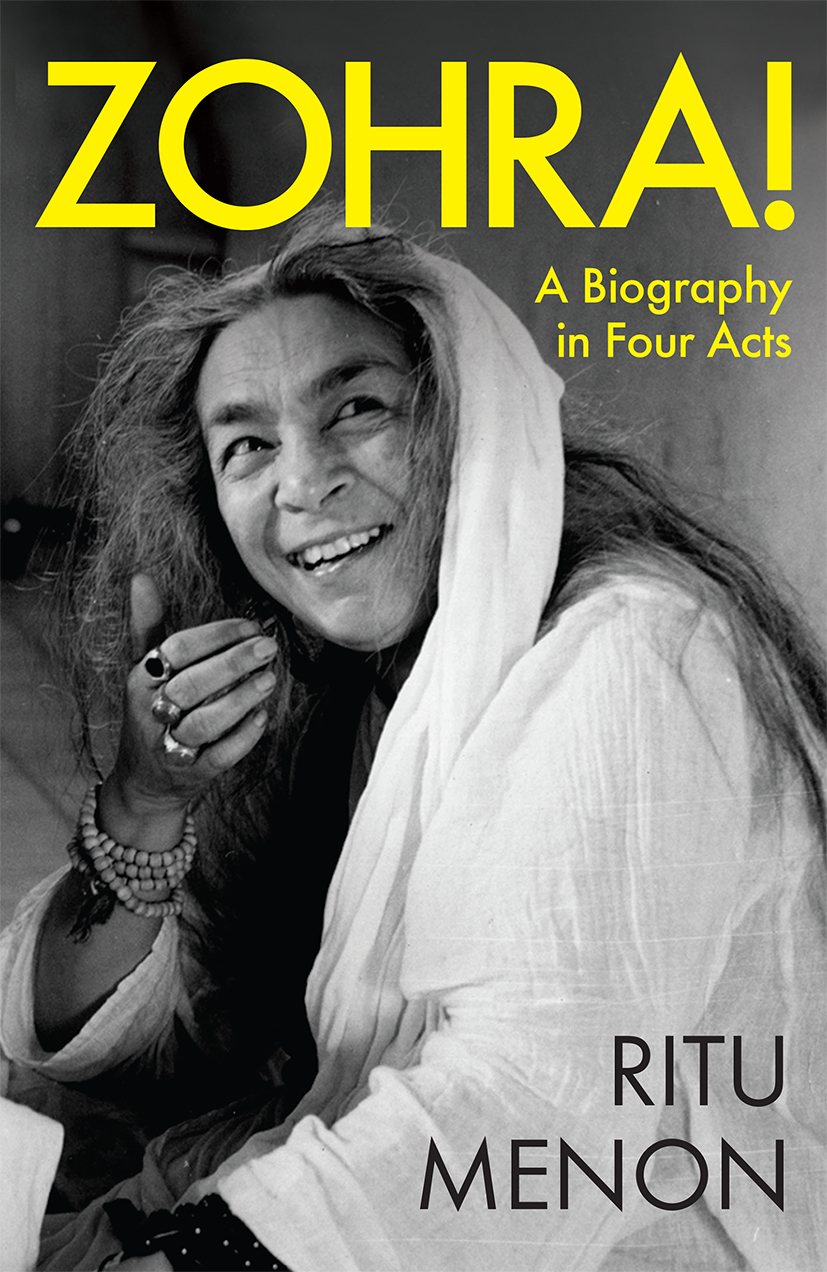

Zohra Sehgal (1912-2014) spanned an Indian century of the arts and became the only woman to make a mark in all the performing arts, with the exception of music, within the country and abroad.

Ritu Menon’s Zohra! A Biography in Four Acts traces her remarkable journey — from travelling to Germany to learn modern dance at the age of eighteen, to playing the unconventional grandmother well past the age of eighty.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Curtain Call

In 1992, when Zohra was eighty, she told a young journalist: It is not easy to evaluate a lifetime’s work… I feel that my only contribution is that I might have inspired some people to do what they most wanted to do… Dedication is essential… seriousness and devotion are imperative. You cannot flirt with either acting or dancing… you have got to be a professional, you cannot cheat or pretend—it shows.1

In 1930, when Zohra was eighteen and zoomed across the Continent in a souped-up car, nothing could have been further from her mind than dedication, devotion and seriousness. Then, it was all impulse and adventure; she wanted to see the world, to enjoy herself, to experience the unexpected and exciting, to escape from the conventional. Above all, she knew she didn’t want to get married.

She knew, too, that she was a child of privilege, able to indulge her fancy because her circumstances and her liberal, cosmopolitan upbringing allowed her to defy convention. No young woman from her background would have been left alone in Europe, unchaperoned, to pursue a choice arrived at by fluke—dance! She had never danced in her life, and at eighteen was too old to begin training in a classical form. So it had to be movement and eurhythmics, which is what she studied at the Mary Wigman school. No young woman, then, would have been encouraged to develop her Inclination further by joining the troupe of a dancer who, although famous for his creativity, was already notorious for his bohemian lifestyle. And few, very few, young Muslim women would have had the confidence to marry a Hindu man much younger than them, against parental approval—but by then, living an unconventional life had become Zohra’s signature.

For all that one might think that hers was a life crowded with serendipitous events, look closely and you realise that at every stage she carved out her own path, making the most of the small, mixed opportunities that came her way. She might well have said, ‘You cannot flirt with life.’

In Europe, Zohra met a variety of men socially: ‘[I] fell in love, had crushes on men, and men were interested in me— all this would have been impossible for me in India.’2 She discovered the splendours of the world through travel, and the exhilaration, the sheer artistry of what she could do with her body through dance. She cultivated both passions assiduously, and the joy she derived from them remained with her for the rest of her life. At the Wigman school, she understood the importance of discipline, of the daily routine of exercise and repetition, and had her first lessons in what she later extolled: seriousness of purpose. Stretching the body to its limits, recognising that her body was her medium, her means of communicating, her key to increasing self- awareness and to nurturing her individuality. Dancing with Uday Shankar she realised its glorious potential, and the intoxication of the stage—footlights, applause, recognition. As part of his troupe, she could indulge both her love of travel and her love of dance.

At the Almora Dance Academy, she discovered a new love, the love of teaching, where she could finally put her pedagogic diploma to use. She excelled at it, and when she left Almora for Lahore she chose to start a school of dance rather than continue to perform. The offer to be dance choreographer at Prithvi Theatres gave her an opportunity to teach as well as to create, even though she herself did not dance on stage. By a happy coincidence she taught again, briefly, at Ram Gopal’s school in London, but she admitted many years later that she had been ‘too lazy to take on the entire responsibility of teaching or directing my own pupils according to my convictions and experience’.3

Zohra was an accidental actor. As she said repeatedly, she had neither the face nor the figure for playing a heroine, so it is no surprise that she was never cast as one. ‘My face is like Ho Chi Minh’s,’ she once joked, ‘and my profile resembles that of Alfred Hitchock.’ Yet, she made her name as an actress. Hitchock and Ho Chi Minh she could deal with, but Uzra as leading lady in Prithvi Theatres was another matter. Zohra adored her younger sister, but as they were both with the company incipient rivalry could not be ruled out. ‘Uzra was the beauty of the family’, she told reporters in Lahore ‘and I was wildly jealous of her, but I wasn’t about to give up without a fight! I exercised madly and set out to cultivate my charm till everyone thought I was beautiful. Plus, could act.’4

As a dancer in Uday Shankar’s Company, Zohra’s looks had never been a consideration. His productions usually called for ensemble performances, and on the few occasions that she danced a duet her partner was always male—Uday Shankar himself or Kameshwar. Now on stage with Prithvi Theatres, with actors like Indumati, Uzra, Shaukat Azmi, Pushpa and others, she realised she would need to focus on her Strengths and hone her acting skills, and do so assiduously. Fortunately, for her, she discovered that she loved to act almost as much as, if not more than, she had loved to dance. It marked a turning point in her development as an artiste.

The fourteen years in Bombay, and with Prithviraj Kapoor and Prithvi Theatres, were possibly the happiest in Zohra’s life, professionally. She was living in a community of artistes—filmmakers, actors, writers, journalists—all of whom were pressing against the boundaries of their chosen vocations, furiously experimenting and creating, intervening energetically in the social and political churning taking place in the country. In IPTA, for the first time, she was part of theatre for the common person, performed in neighbourhoods and at street corners, accessible to everyone. This was theatre with a specific purpose, communicating a progressive, political message. It was new for her. Uday Shankar had been radical in his own way, a creative powerhouse, but politically, more or less disengaged. IPTA’s productions brought her face to face with social realities that, in the years preceding independence, had begun to stir the national conscience.

Prithviraj’s theatre for social change, theatre with which he sought to cover the length and breadth of the country, complemented what Zohra experienced at IPTA; but here, the scope for enhancing her potential was far greater, as theatre was the primary purpose of the Company. It was at Prithvi, and through Prithviraj, that she understood what dedication to a vocation implied and entailed. That understanding was foundational. As she toured with the Company and carefully observed Prithviraj’s charisma, his apparently effortless skill in drawing people out—actors, audiences, stagehands, children— she realised that in order to communicate effectively you had to shed your ego, cultivate the common touch.

IPTA, the Progressive Writers’ Movement, Prithvi Theatres were at the cusp of change in the decade just prior to Independence and the decade after. This period saw an explosion of innovation in the arts, architecture and cinema. Uday Shankar had already introduced the modern in his choreography and his compositions, and Zohra collaborated actively with him in many of his productions. She did little of that at Prithvi, but her years with the Company convinced her that acting was her life. She owed this awakening to Prithviraj Kapoor. ‘I am in love with acting,’ she was to say later, ‘I do not think I can survive without it.’5

Kameshwar died in 1959, Prithvi Theatres closed down, and Zohra stopped acting. For three years she lived in a kind of suspended animation, bereft of all the resources, relationships and activities that had sustained her. Kameshwar’s death, the more or less simultaneous closure of Prithvi Theatres and Uzra’s final departure for Pakistan marked the kind of turning point in her life from which there would be no going back. A subtle transformation was taking place within her—she realised that the only skills she had were dancing and acting, and that, thus far, she had simply, and conveniently, attached herself first to one celebrated artiste and then another, ‘basking in their glory’. She was on her own now, single, the sole breadwinner, not just for the time being but for the foreseeable future. And she was forty-eight years old, with two very young children to look after. A stock-taking was necessary.

Yes, she had been with Prithvi Theatres for fourteen years and acted in all their productions, but she was aware that she had no formal training at all. Looking and learning from Prithviraj Kapoor—who readily admitted that he was not qualified to teach anyone how to act—was sufficient for the kind of theatre they were doing; but she knew intuitively that for her to make acting her career she needed to be more professional. Hence the British Drama League.

There was nothing impulsive about her decision to seek work as an actor in England, just a practical reckoning that any experience gained on the London stage—should it come her way—could only be to her advantage. She needed to work as an actor, but also to earn a living, and so she arrived at the second critical decision in her current situation: she would take whatever she was offered with regard to both. She would suppress her ego as an actor; and as an individual, relegate her aristocratic lineage to the background. She would, in a manner of speaking, make herself over. Acquire a persona.

Present another face to the world. A dresser at the Old Vic, a glorified ayah? Why not? No one knew who she was in London and, looking on the bright side, she could see as many plays as she liked at the Old Vic. A seamstress at Pettits? A new skill. Managress at the Tea Centre? The better to entertain her friends and co-workers at the BBC with. Waiting for her luck to turn, recalling, at every low point, Kameshwar’s adage: ‘If you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.’

1. The Sunday Observer, July 26-August 1, 1992.

2. Erdman and Segal, Stages, p. 216.

3. As told to Shreela Ghosh, in Bazaar, quoted in Erdman and

Segal, Stages, p. 262.

4. The Friday Times, Lahore, March 11-17, 1993.

5. The Indian Express, December 29, 1991.