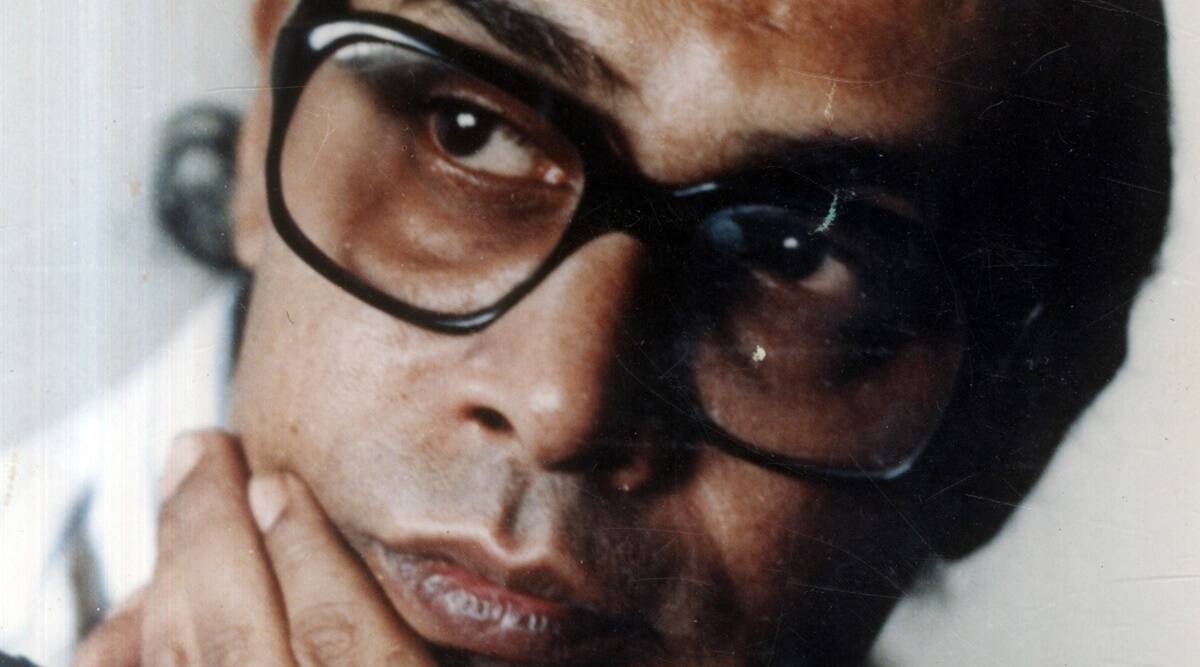

The Kolkata-based Satyajit Ray Film & Television Institute (SRFTI) paid tribute to Bangla auteur Buddhadeb Dasgupta yesterday with an elaborate lecture by filmmaker Ashoke Viswanathan. Buddhadeb, after a dynamic career that began approximately in the ‘70s and in which produced some of the most iconic of Indian films, died at Kolkata on 10th June, Thursday. Currently the Dean of SRFTI, Ashoke spoke at length about Buddhadeb’s style and contributions by tracing his influences right from his time as a student. His running theme or argument throughout the lecture was the evolution of Buddhadeb’s style and how it did not bother to adhere to rigidities or rules of any kind. An experimenter of the finest kind, Buddhadeb was like the 20th century Japanese master Yasujirō Ozu (1903-1963), whose craft too had travelled across varied “formalistic structures”, said Ashoke.

Buddhadeb began writing and publishing poetry from a young age, and was deeply influenced by the poetry, literature, theatre and cinema of the world even as a student of Economics at Kolkata’s esteemed Scottish Church College during the late 60s, early 70s, said Ashoke. He added that Buddhadeb was one of the many prominent Bengali filmmakers who built their careers out of the grants provided by the then state government, which had put in a lot of effort on this front.

By 1977, Buddhadeb released his first film, Duratwa, based on a story by Sahitya Akademi Award winner Shirshendu Mukhopadyay, whose work at the time reflected a heavy influence of Albert Camus and Franz Kafka. According to Ashoke, Duratwa was one of the earliest films to speak about urban realities and relationships.

Buddhabed’s film Grihajuddha (1982) explored the theme of a political thriller, made popular internationally by Costa Gravas in 1969 with his film Z. Despite the theme, the context of Grihajuddha and the next Andhi Gali was the ‘70s urban landscape. “Duratwa, Grihajuddha and Andhi Gali can be considered a trio”, said Ashoke in the lecture. “Grihajuddha was one of the few parallel films that did well among the masses as well”, he added. Going into the technical and aesthetic details of Buddadeb’s cinema with equal depth, Ashoke said that till Grihajuddha, Buddhadeb hadn’t used the track and trolley for ideological purposes. This was however done from his next one, Phera (1988), “considered by many to have been inspired by Federico Fellini’s Amarcord (1973) due to its level of eccentricity”, according to Ashoke. Phera won several awards and was selected to the most important “Competition” section of the Berlin Film Festival. This was the first time Buddhadeb’s film garnered so much international attention.

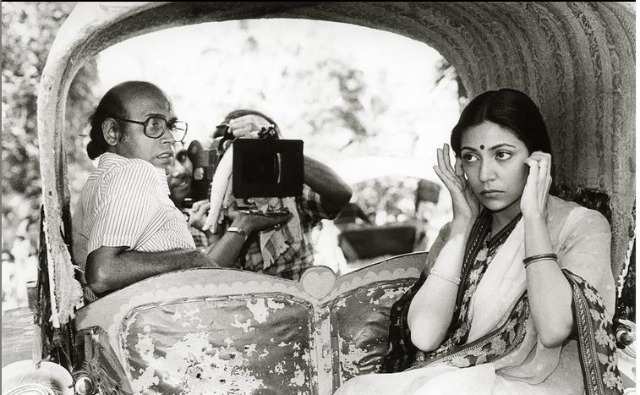

It was from Bagh Bahadur, the 1989 film based on Prafulla Roy’s short story, that Buddhadeb’s style began to “gradually emerge”, where we see the parallel tracking of the landscape. The track and trolley in Bagh Bahadur is a tool for analysis, as per Ashoke — from where the filmmaker goes on to use it more in the future. The film explores the dying artform of “Tiger Dance” and features a number of cultural motifs that go on to become recurrent aspects of Buddhadeb’s films from then on, says Ashoke. The tiger, in the film, is a powerful “metaphor for the conflict between arts and commerce”.

“From here, there is a huge ascendency in terms of artistic sensibility in Buddhadeb’s films”, says Ashoke who then goes into the details of films like Charachar (1993), that features surreal elements, Damul (1985), that uses the track-trolley for greater intellectual probe almost to the level of obsession, and Uttara (2000), with its “hydra headed narrative”.

Charachar established Buddhadeb’s courage to carve out “unique cinematic configurations”, as Ashoke put it, and his will to challenge the hegemony of Hollywood canons like the celebrated “Decoupage Classique” and such of the time. In Damul again, the extreme use of the track-trolley made it clear his intention was not his audience to “dissolve” into the story, but perhaps to stay out of it and be constantly aware of the process — “like (Jean Luc) Godard at times”, Ashoke added. “One feels as though the camera style is having a conversation with the art director in the film itself”. In Uttara, which speaks against the unequal society, the “visual configuration itself was a form of protest”, argued Ashoke.

“So Buddhadeb was someone who refused to conform throughout his life who often reminded me of the great absurdist Samuel Beckett”, concluded Ashoke. “He on creating films in an uncompromised manner, not bothering to make them intelligible in any way. They could have been obscurantist or esoteric at times, but his commitment, ultimately, was to cinema”.