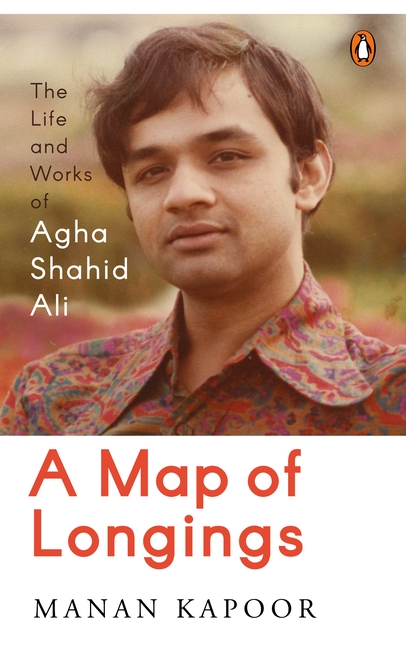

In A Map of Longings: The Life and Works of Agha Shahid Ali, Manan Kapoor explores the concerns that shaped Shahid’s life and works, following in the footsteps of the ‘Beloved Witness’ from Kashmir to New Delhi and finally to the United States. He charts Shahid’s friendships with figures like Begum Akhtar and James Merrill, and looks at the lives the poet touched with his compassion and love.

He also traces the complex evolution of Shahid’s evocative verses, which mapped various cultures and geographies, and mourned injustice and loss, both personal and political. Drawing on various unpublished materials and in-depth interviews with Shahid’s family, friends, students and acquaintances, Kapoor narrates the riveting story of a major literary voice and presents Shahid’s poetic vision, revealing not just what he wrote but also how he taught the world to live.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter, “In Exodus, I Love You More”.

‘Shahid’s process of submitting to journals was remarkable,’ Padmini recalls. When he was done with a poem, he decided on four to five journals that he thought would be best for it. However, in those days, one couldn’t submit poems simultaneously to all journals, and so Shahid had to wait for an acceptance or a rejection. In the meantime, he continued to revise his poems, and by the time he received a rejection letter, he already had the cover letter ready and knew which journal the poem was going to next. ‘There was no room for being crushed by the rejection or taking a couple of days to recover,’ Dingwaney remembers. ‘He was completely relentless.’

The poems improved in style and language with each version. Shahid had a ritual of checking for letters—especially rejection letters—while leaving or returning to his room. In an interview, he confessed that he never worried about rejections. ‘There were zillions of them coming . . . I never took it personally, or maybe I was just shameless,’ he said.1

Hena Ahmad, Shahid’s elder sister, remembers that when Shahid was eighteen, he received a personalized rejection letter from a magazine called Quest; the letter said that his poetry was ‘far below their standard’ and requested that he read more before sending anything again. Through Eliot’s influence, Shahid had already learnt that his poetry couldn’t be an overflow of emotion and had come to the conclusion that he had to depend more on the trickery of language than on just raw, organic passion. Poetry was an exploration of pure form. Much later, in an essay, he acknowledged as much and wrote: ‘Content is achieved sincerity. Sincerity achieved through artifice. Emotion tested by artifice.’2

This sincerity and emotion, in Shahid’s case, stemmed from memory. Although he was completely at home in America, his memories of Delhi and of his childhood in Kashmir were with him. As soon as Shahid moved to America, he discovered new poets like W.S. Merwin, Charles Simic, Robert Lowell, Adrienne Rich, John Ashbery and James Merrill; their use of language, their formal schemes and how they approached their subjects, deeply influenced Shahid. However, rather than camouflaging with the environment and American mannerisms, Shahid chose to stand out, which made all the difference.

Even though Shahid read American poetry extensively, he didn’t allow America’s minimalism to water him down and introduced the expansiveness of Urdu poetry into the bloodstream of his writings. His attachment to his roots and the distance from his homeland impacted him deeply. In an essay, Shahid wrote that ‘the moon would shine into my dorm room, and I remember one night closing my eyes and feeling I was in my room in Kashmir’, and that ‘sometimes in a bar at 2:00 a.m., like so many Americans, I felt alone, almost an exile (except when I got lucky!)’.3 Even though he viewed Penn State as ‘a home’ if not ‘home’, looking back at his initial years there, he called his move to America an ‘inescapable exile’.4

Shahid was never banished from a nation state or exiled because of his political stance; he was simply an immigrant and was aware of that. He also acknowledged that the word exile didn’t have the same resonance in the modern-day world; one could simply take a flight and reach home. He was aware that his condition wasn’t that of an exile but simply a matter of choice.

As he said in an interview: ‘You constantly meet people who are immigrants and who say, oh, I feel like I’ve lost my culture and I’ve lost my roots, and I say please don’t be so fussy about it. The airplanes work. I mean, if you have a certain kind of income, whether you live in Bombay and fly to Kashmir, or you live in New York and fly to Kashmir, for a certain group it really makes no difference.’5

He acknowledged that all this talk about exile was, to some extent, poet-speak, but he also believed that there were psychological consequences of distance that existed beyond the definition of the word émigré. Looking back at his time at Penn State, Shahid said that what he meant by the word exile was ‘an entirely new kind of geography, an entirely new kind of sensibility that became available to my poetry . . . [Long pause.] I used ‘exile’ also because, in some ways, when you write in English, in India, you are in some ways an exile in your own land. In some ways. And I know I’m romanticizing.’6

He said that he used the term exile and not expatriate because ‘the former is a term with a lot of resonance, because it describes some of the emotional states that the latter would not’.7 The exilic element is evident in The Half-Inch Himalayas. What emerges from the poems is a sense of distance, evident in the title of the collection. The first poem, ‘Postcard from Kashmir’, which is considered by many as the epigraph to the collection, evokes the ‘ultramarine waters’ of the Jhelum and provides a sense of perspective from which the poet is looking at the Himalayan mountains that surround Kashmir:

Kashmir shrinks into my mailbox,

my home a neat four by six inches.

I always loved neatness. Now I hold

the half-inch Himalayas in my hand.8

1. Christian Benvenuto, ‘Interview with Agha Shahid Ali’, Massachusetts Review, vol. 43, no. 2, Summer 2002, p. 262.

2. Agha Shahid Ali, ‘A Darkly Defense of Dead White Males’.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Christian Benvenuto, ‘Interview with Agha Shahid Ali’.

7. Agha Shahid Ali, ‘Agha Shahid Ali: The Lost Interview’, Interview by Stacey Chase, The Café Review, Spring 2011.

8. Agha Shahid Ali, ‘Postcard from Kashmir’, The Veiled Suite.