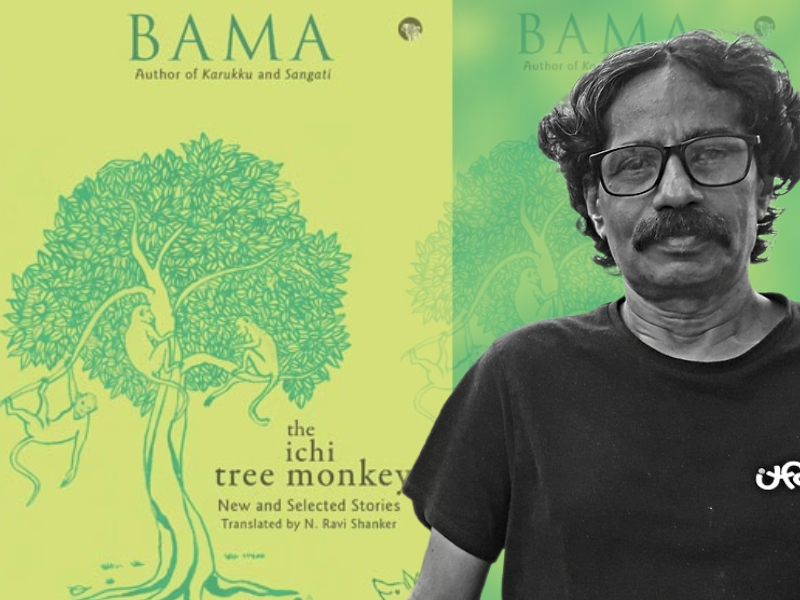

Originating from deep within the hearts of the dalit colonies of rural Tamil Nadu, writer Bama’s The Ichi Tree Monkey has been translated by N. Ravi Shanker. Published by Speaking Tiger, The Ichi Tree Monkey is a collection of short stories on everyday acts of dalit resistance against caste-based oppression in rural Tamil Nadu. Ravi Shanker is a poet based in Kerala’s Palakkad, who has published his original work on various platforms, online and offline. In 2004, he translated Mother Forest: The Unfinished Story of CK Janu, by Bhaskaran, from Malayalam and in 2006, Bama’s Harum-Scarum Saar, from Tamil. Ravi Shanker has also been the co-translator of many works as well as written English subtitles for several Malayalam and Tamil feature films.

In this interview with us, he speaks of his experience translating The Ichi Tree Monkey, and more.

Indian Cultural Forum (ICF): From Esakkimuthu and family in ‘Pongal’ to ‘Empty Nest’, The Ichi Tree Monkey introduces us to a mix of extremely spirited fighters. From the entire collection, could you pick one or two characters that have touched you deeply, have stayed with you till now, and tell us why that is so?

Ravi Shanker (RS): One character whom I cannot remember without a trace of awe and admiration is Malandi Thatha from “Old Man and a Buffalo”. At his age, he is a hero of the kids and while grazing his pregnant buffalo he tells them stories of his valorous battles with snakes. But more of his battles are revealed when his intense hatred for the upper caste landlord is exhibited. He is fearless before him and teaches the boys to be so. At the end of the story, it comes to fore that he had gutted the dad of the present landlord using his own cow against him. Now, a loan is overdue and he is waiting for his buffalo to give birth before gutting the present landlord when he comes to claim the buffalo against the loan. What impresses us is the utter disregard and disrespect he harbours for the landlord and his militant rejection of the low status. He considers him to be equal to the landlord in every way, except that he has less wealth and land. In fact, he is sharpening the horns of his buffalo for the fight ahead. He is a symbol of strong, militant dalit upsurge.

ICF: We’ve often heard how some writers are wary about their work getting translated, due to the fear of losing certain nuances in the process — primarily, linguistic. Is your retention of certain local Tamil idioms, words and zingers, that Bama uses, a way to preserve the nuances?

RS: In this work, the one difficulty I faced was that Bama writes about dalit life in a Tamil that only dalits speak. This is not the same as translating standard Tamil. I consulted a few Tamils, as the language was new to me. But they avoided me as if I had taken a dirty novel to them to read. Hence, I had to use a lot of intuition to translate the words. After doing one or two stories, I got the knack of it and could follow the mind of Bama as she wrote it. I retained many words with the local flavour because I felt their speech pattern had to come out as it is. I then travelled from Palakkad to meet Bama, living in Kanchipuram. Sitting in her small room, we discussed what I had done and she suggested many changes. I understood the pattern of her writing by then and the next draft got approved. This draft left many Tamil expressions intact without even a footnote to explain.

ICF: As a Malayali who lives in Palakkad, the geographical proximity (to Tamil Nadu) would have certainly helped, but even then, the scenarios are not all the same. How did you deal with it, if there were any gaps in relating to the socio-political realities present in the stories, or was it all too familiar?

RS: As a person, I keep abreast of the political changes happening around me and while translating, I was not ignorant of the dalit issues in rural Tamil Nadu. I had already read novels like Indira Parthasarathy’s Kuruthippunar and the works of Babasaheb Ambedkar. One gets an understanding from not just the stories translated, but also from the numerous incidents of dalit oppression we read about or watch in documentary-feature films. My politics is oriented towards dalit emancipation. Without understanding the politics or sympathising with it, none of these stories could have been translated. It is not just a case of mechanically rendering into English what is rendered in Tamil.

ICF: You’ve been a translator for years now and you’ve also translated Bama’s work before. Compared to other authors’, what distinguishes Bama’s work for you as a translator, professionally and personally?

RS: I must say that this book is an extension of Bama‘s stories I had translated earlier and those stories which are new have been appended to it. I have translated from Tamil, works of Bharathi Dasan, Azhakiya Periyavan, Leena Manimekalai and the like. Azhakiya Periyavan is a dalit writer, but his stories do not focus on rural life as such. Bama is entirely different, as her stories are only about dalit life in rural Tamil Nadu. All her stories are drawn from dalit life in villages. I do have a rural background in Kerala, but it has no comparison to the Tamil country. Much of the stories are not from a remote past, but present day Tamil Nadu. This is something fascinating. I was drawn to these stories because of the simple life they depicted, unlike Malayalam literature today which seems to have left all this behind to become post-modern.