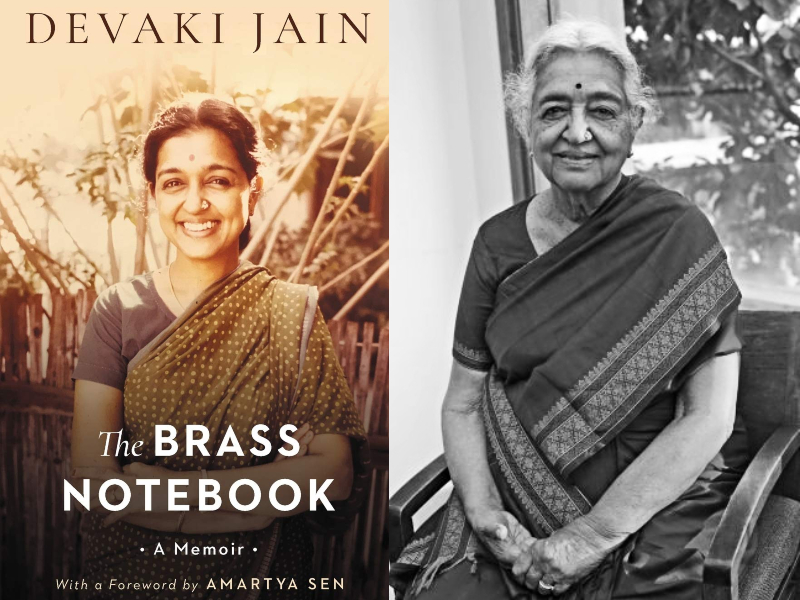

Renowned feminist economist, academician and women’s rights activist, Devaki Jain, recounts her story and through it, that of an entire generation and a nation, in her memoir, The Brass Notebook. She begins with her childhood in south India, a life of comfort and ease with a father who served as dewan in the Princely States of Mysore and Gwalior — along with the restrictions of growing up in an orthodox Tamil Brahmin family. From there, the memoir travels across Ruskin College, Oxford and Harvard, and through her professional life, which saw her becoming deeply involved with the cause of women workers in the informal economy and their fight for a better life.

Below is the ICF Team‘s interview with Devaki, in which she speaks about the book and her life, along with some crucial excerpts from it.

ICF Team: What would you say, in retrospect, was the turning point of discovery — rethinking economics, but also politics? When did the need for change, and inclusion, whether of gender, caste or class, all come together for you?

Devaki Jain (DJ): It seems a bit unbelievable right now, but I would like to confess that it was the announcement by the UN of a women’s year in 1975 and then a world conference on women that started me off. There was, so much excitement and communication.in the air. In India, I had been invited to prepare a book on Women for the Indian government to submit at the world conference in Mexico. Obviously, I could not do a full book, not knowing enough about the subject. Hunting for information on this issue opened my eyes to what is now called gender. In the meantime, I had also got engaged with learning about women through what I would call ‘reality check’.

The reality check was that I could see with my eyes that women were working everywhere — on the streets, in the market and of course at home but they were not seen as labour, so these visual encounters moved me to looking at both counting, analysis and policy. In the middle of all this, was my attachment to Gandhi and that added to the question on whether the economics or politics we were practicing was relevant to what was happening at the ground level. While these were the streams of thoughts in my mind, it all came together in the process of preparing for the book on Women.

From The Era That Shaped My Life

I like to call myself and those of us who were young adults in India in the 1950s, the before midnight’s children. Unlike Salman Rushdie’s protagonists who were born at the very midnight hour of August 15, 1947, the moment that India was declared free from British rule, I was born in 1933 and was a teenager at the time of Independence, and a young adult as we threw ourselves into the work of a new and free India. I would say that we experienced an India which we still fantasize about, and which also shaped our politics profoundly. I would go further and suggest that we got deeply attached to some ideas, ideologies and aspirations that were born of that experience that we are not able to shed, even today, in our eighties. I was fourteen years old when India declared Independence on the fifteenth of August, 1947. I was living in the city of Gwalior in north India, where my father was the dewan of the Gwalior State—the chief minister, in today’s parlance. We, his family, were somewhat = screened from the turmoil, the agonies as well as celebrations that were going on, especially in New Delhi. But like a new arrow, the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi pierced through our household. As my father has written in his memoir, Of the Raj, Maharajas and Me, a few days prior to the assassination of Gandhi, the assassins had been in his drawing room, angry with him for restricting the activities of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or RSS, and also for not including its party members in his cabinet. They had abused Gandhi and amongst others, my father, for supporting the Muslims and made death threats against Gandhi and my father. My father’s term as the dewan of Gwalior ended with the integration of the States into the Republic of India. A Chamber of Princes had been formed, mandated with the task of forging an agreement with the princes to join the Republic. He was engaged as the member secretary of this chamber. That task was also done, so he was getting ready to return to Mysore State. He was commended for having done the job successfully. Gandhi had heard from Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, then the home minister, that my father had done well with that task and perhaps wanted to commend him for another government posting. So he had sent for my father and given him an appointment, ironically for January 29, 1948—the day before he was assassinated, January 30.

My father recalls how Gandhi asked him to stay on after the meeting, and pointing to a few people who were agitating outside his chamber, said: ‘You see those poor people standing there? They are from Bannu. They have come all the way to see me. One of them was quite angry with me today. He told me, “Gandhiji, you should die.” I said I will not die until my inner voice says I should. And do you know, Sreenivasan, what he said?’ Gandhiji raised his hand in a characteristic gesture and said, ‘He said “My inner voice says you should die.”’ Thus, the very next day when my father heard that Gandhi was shot dead, he was devastated. His conversation with Gandhi on that evening was full of portent and left him and all of us, his family, not only deeply shocked, but politicised.

ICF: You write of many women who were associated with the women’s movement in some way or the other. Their lives must have charted new and non-conformist paths based on their conviction. It would be interesting to hear about how differently this played out in, say, Fatema Mernissi and Gloria Steinem, both strong women of ideas, and both friends of yours?

DJ: In question 2 you ask, how differently our paths played out and you give me Fatema and Gloria as illustrations. I would not go along with that, each was handling their realities, from what they found around them, what they experienced personally and you might say that it was similar too.

I am beginning to believe that there is a fire that burns in the belly of some of us in confronting situations whether it is gender, class or environment. That is, I do not see a difference between Gloria and Fatima, even though their locales were different.

From Rethinking Economics

If I wear my cloth over my shoulder like you upper-class women, will you clean my shit? Leave us alone. You do not want us to become strong. Then who will do your dirty work? We are doomed to labour forever,’ screamed Thimmi, a Dalit woman from Chikmagalur in the state of Karnataka. She had a thin, torn piece of cloth on her body, wrapped under her arms and coming down to just below the knees. I was wearing a sari, draped around me, with the pallav thrown over my shoulders.

It was 1977, that eventful year. I was in Thimmi’s village as part of a team along with the philosopher Ramachandra Gandhi, campaigning for the Janata Party, a new political formation that had come into being after the end of the state of Emergency that Indira Gandhi had declared two years earlier, suspending civil liberties and instituting press censorship. Lakshmi and I, and even our son Gopal, then ten years old, had been active in campaigning in that election, our house in Delhi turning into one of the centres of resistance, to the point that we were under constant police surveillance. We were all admirers of one of the leaders of the anti-Indira Gandhi movement, Jayaprakash Narayan, a socialist and Gandhian whose moral integrity had won him admirers from across the country, cutting across ideological divides.

Ramachandra Gandhi, my companion during some of my travels during that election, was a grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, and it was hoped by people in the Janata Party that his name might attract Dalit voters. In those days, the name of Gandhi was still associated with the emancipation and self-assertion of Dalits. (The move among Dalits away from Gandhi and towards Dr B.R. Ambedkar, a figure representing a different sort of politics and a more radical opposition to the caste system, occurred over the four decades since that election.) Ramachandra Gandhi respectfully asked Thimmi to vote for the Janata Party candidate, and it was then that she uttered those cutting words. On a different occasion, this time while visiting a coffee-curing shed in Karnataka, I remember the words of Kempamma, a 45-year-old coffee worker, about her male supervisors at work. ‘What do they know? We are to do nothing but bow our heads. I have a sick child, I am late, the family eats nothing that day, I bow my head. The union goes on strike, we starve for fifteen days, then are taken on for ten paise more in wages, and still I bow my head.’ She suited the action to the word, like a swan disappearing into the water, all the while beating her forehead with her palm.

Then there was Fatima Bi. Fatima Bi lived in Delhi, in the area around the great mosque, the Jama Masjid, and was one of the many Muslim women there who did intricate embroidery in silver and gold thread. It was they who prepared the various decorations, palla, that adorned the mukuts, headdresses, worn by Hindu brides and grooms at weddings, and sold to them by the innumerable shops selling this kind of thing in the streets around Chandni Chowk. I remember arranging for her to visit the city of Ahmedabad where she found to her shock that the mukuts were being sold there at prices almost ten times as much as she sold the palla. She threw herself to the ground at the sight of the prices and, she later told me, beat her forehead to the floor, crying, ‘Ya Allah! Is this what you call justice?’ From that moment, she refused to put her hand to the needle till wages for her kind of embroidery were raised to a rate that better reflected the market value of her work. In a different context—a discussion of women callously divorced by their husbands, or having their incomes squandered by them—I remember another of her laments: ‘Ya Allah! Mard kyon banaya?’ Why did you create men? These conversations were part of a pattern I have learnt over the years to see. Whatever the sector, female workers, despite working for hours every day with their hands, with a skill and physical effort no less than that of their male relations, and a commitment to cooking and childcare to which those men make no contribution, made very little money. Exploited by brokers and middlemen, little of the profit made on their work was reflected in what they were paid.

During my visit to the tea plantations in the hilly regions of Karnataka, female tea-pickers spoke of being continually propositioned by their male supervisors. Only those who agreed to provide sexual favours would have their bags of tea leaves weighed correctly, and therefore, be fully paid for the work they had done. Anyone turning down sex would have their bags deliberately underweighed. Economic exploitation—of which men were also victims—went hand in hand here with sexual exploitation.

I have related some of the aspects of my own experience—of abuse, harassment, direct and indirect discrimination—that made me receptive to the testimony of these women. But my work in the women’s movement was in large part inspired, and later sustained by, my encounter with these women, with experiences of life, the economy and the patriarchy radically unlike mine. Thimmi, Kempamma, Fatima Bi—these were some of the women who taught me much of what I have since come to know about gender. They, more than any theorist, taught me my feminism. They have shaped the themes of my research and writing, provided much of its subject matter, and it is to them and others like them that I have always felt accountable.

ICF: Between then and now — has the unequal world changed? In what ways would you say it is different, and in what ways the same?

DJ: Has the unequal world changed? I would say it is changing but as you say, it is different and in many ways inequality has increased and lack of understanding between identities has also increased and therefore, there is greater distress and injustice in society.