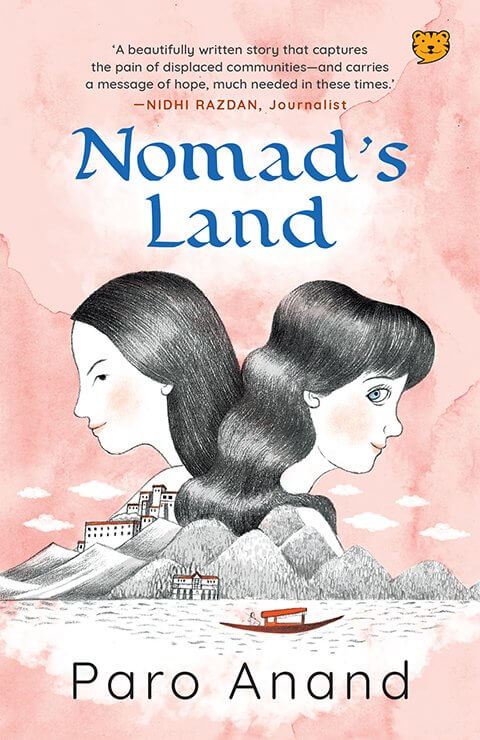

Paro Anand’s Nomad’s Land is the story of two girls growing up in a big city, Shanna and Pema, who meet at their new school. They come from displaced communities—people who had to flee their land to escape persecution. Shanna is a Kashmiri Pandit, and Pema comes from a nomadic tribe whose people called the high mountains beyond India their home.

As Shanna and Pema become friends, they get to understand their own and each other’s stories. Nomad’s Land talks about the effects of terrorism and displacement, and about the healing powers of hope, friendship and reconciliation.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Pema was always impatient when her parents, or the many uncles and aunts who had settled here, talked of the old days. But Mola talked about them as though they were wonderful stories: full of adventure and magic. It was from Mola that Pema learnt to love her roots a little. She came from a proud race of a small tribe who lived in the Zarim Basin. The massive Qhushava range of mountains lay to the north-east of their beautiful valley, just beyond India. Her people were nomads who wandered the great plateau freely with their families. With animals to help them. Children were born and elders died while they roamed. For them, the sense of belonging and home came when they pitched their yak-wool tents and hung cradles for the new babies to sleep in. Where their animals could pasture.

They belonged to the open world. And this world belonged to them. They carried no passports, no permits. There was an umbrella term for them all: the Qhushavans. It literally meant the Happy People. The term referred to several tribes: the Zarims, the Sonamaargs, the high-altitude Qhushahas. Pema knew that she belonged to this last sub-tribe: the ones who lived on the highest part of the plateau and were supposed to be the happiest. And the bravest.

Everywhere they went, they were welcomed. The people needed them, their wool, their salt. They needed them for their seemingly infinite knowledge of roots and leaves and barks of plants from which they made potions and lotions. Medicines that closed wounds and stilled unwanted shakings. As for the Qhushahas, they needed the people for food and shelter if the weather was too severe. And sometimes for medicine if someone was too sick for the old ways.

But most of all, the plains people and the tribes needed each other for their stories. The nomads brought stories of strange creatures in dark crevices. Creatures that were sometimes violent, but mostly kind and helpful. They could bestow magic upon you and you could cover vast distances on winged feet, or calve a yak with no trouble or time being consumed. They could hold off a snowstorm or high wind as your caravan sought shelter. Though sometimes the high wind was not just a wind, but a monster, an enemy. There were the Wise Elders: the Kurmajo, elder men, and Kurmaji, the elder women. There weren’t many of them left now and so the words to describe them had almost ceased to exist. They were the closest that the Qhushavans had to priests. Mola said that they could tame the wind and storm. They could wrap the whistling wind on their fingers and fling them towards those who may be out to cause trouble. Those typhoon-like winds could lift anything—trucks, homes, trees. And wicked men. The Kurmaji and Kurmajo dealt with major issues. For the rest, the people communed directly with their god, there was no need for a go-between.

And from the plains people, the nomads came to know the news of big folks, the leaders, the government.

Ah! The government.

That is how they got to know that the big city folk had decided that nomads had no place in this world. Nor could the world belong to them. Why? Because here were a people who lived without rules, without laws hovering over their heads like swords. And this could not possibly be allowed. So they made laws that would govern the nomads. Laws that governed them although they knew nothing about them.

The nomads would need permits and passports from here on. They would not be allowed to cross borders. They were to be given birth and death certificates. And anyone without papers would be prosecuted. Jailed.

This last word had brought a shudder to the spines of the tribe as they shared their hookahs one night, trading stories. The thought of being locked up in a small, dark room was their idea of what hell must be like. These people of endless plateaus and forever skies could not live in a house, let alone a locked room. A room where light and air could only poke at, but not enter.

And from jail, they would be tried in unknown courts and then be forced to leave. But where would they go? These pastures were their home, they had nowhere else. For nomads have no land.

The tribesmen could not understand how they were to adapt to these rules. What about marriages, births? How would these be certified? It had never been done, because their own ways were so different. A simple exchange of flowers and a song of blessing signified a wedding. A birth was celebrated by honey and yak milk boiled together as a blessing that the child may have a life of plenty and sweetness. The children belonged to everyone. All elder women were called ‘mother’, all men were fathers. The children were brothers and children by tribe, not by mere blood and DNA.

But the plains people, the lawmakers, could not and would not even try to understand that these tribespeople had always lived by rules. Their own rules. They were declared to be barbaric. They had to be brought into the fold of so-called civilization. They must be taught the language of civilized beings. The Qhushavan language had its own words, but there were no tedious rules of grammar. The idea was to communicate, what use were rules when the speaker could make herself understood to those she spoke to?

More important, why were they being expected to change their ways all of a sudden? They had lived like this for countless centuries. Their ways had been mutually beneficial to all. They needed no land to call their own, so there was more for those who wanted to own it. They brought from the high mountains what the plains people needed. Things like salt and yak wool, medicinal plants that only grew in the highest peaks where the snow never melted. Things that the plains people could never access otherwise. And they took only what they could easily carry with them. They knew a lot about livestock and most people waited till the nomads came to cure a lame horse or an infertile cow.

They didn’t have much money either. But they didn’t need much. And they owned no locks, so where would they even keep the money? If the lame horse walked, or the infertile cow became pregnant, the plains people would load the tribe with food, clothes, sometimes even toys for the little ones to play with. Most often, it was the nomads who would refuse to take any more. They only carried as much as they needed. These were not an avaricious people.