Sonipat, Haryana: Most of India first heard of Nodeep Kaur on 2 February, when Meena Harris, niece of US Vice President Kamala Harris, drew global attention to the arrest of a 24-year-old labour organizer in Haryana, who, by then, had been in jail for 26 days, accused of 11 criminal charges.

Even as her family alleged she had been beaten and sexually assaulted in custody—which the police denied—a local judge had refused bail. Few had previously heard of Nodeep Kaur, what she did, and her work in a grey industrial area in this small northern Indian town, except the hundreds of workers that she and her colleague Shiv Kumar, 23, worked amongst.

Their cases came to public notice after they made common cause with protesting farmers, revealing hardscrabble lives, limited opportunity and the government’s discomfort with young, educated workers collectively demanding legal rights amidst an economic decline.

On 22 February, the High Court of Punjab and Haryana will hear a new bail application for Nodeep, 42 days into her incarceration.

On 19 February, the High Court ordered for Shiv Kumar, a frail but intense young man with partial eyesight, an “immediate” medical examination, which his family alleged was being denied to him during the past four weeks in jail. The court ordered jail officials to allow Shiv Kumar a meeting with his parents and counsels, which too had allegedly been denied.

On 24 February, the High Court will hear Shiv Kumar’s and Nodeep Kaur’s cases, based on anonymous complaints that Kaur was ill treated in custody. Sonipat assistant superintendent of police Nikita Khattar denied allegations of custodial torture. “I have examined records that show Nodeep was taken for a medical exam the same evening as her arrest,” said Khattar. “She (Nodeep) refused examination for sexual assault at the civil hospital, two women personnel accompanied her till Karnal jail.”

Lawyers assisting Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar spoke of police bias and errors in the investigation, such as in the criminal complaint of 12 January, where the police are both the complainant and the investigator, registering more than one case for the same alleged offence.

“In Kaur’s case, the investigating agency—the Haryana police—delayed giving her family documents, such as the FIR (first information report). This is a tactic to scuttle the investigation,” said Tarannum Cheema, a lawyer aiding Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar. “In Kumar’s case, there are glaring gaps in Haryana police’s conduct, as he was not even properly produced in a magistrate’s court after arrest.”

Cheema said they had requested the High Court to transfer the investigation in both cases from the Haryana police to the Central Bureau of Investigation. Police records show Shiv Kumar was arrested on 23 January, but Kumar’s colleagues alleged he was kept in illegal custody from 16 January onwards and tortured.

On 12 February, Article 14 sought comment from Sonipat superintendent of police J S Randhawa. We will update this story if and when he responds.

On 20 February, when Shiv Kumar was brought to the Government Medical College in Chandigarh, Kumar’s colleague, Jasminder, a law student, said he saw injuries apparently sustained in police custody. “Shiv was not able to walk easily as his feet were injured,” he said. “His toe-nails had turned blue from beatings, resulting in clots.”

An Era Fraught With Tension And Limited Opportunity

Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar worked in a state that was one of the first to rein in labour inspectors and loosen labour laws, even suspending them altogether for two months during the lockdown in 2020. This was the immediate source of friction that heightened worker-owner tensions, providing a glimpse of how India’s demographic dividend was playing out in a pandemic era of shrinking economic opportunity and little social security for millions.

In 2018, about 369 million people—about 80% of India’s workforce of 460 million—were self-employed on farms or worked in commercial enterprises with fewer than 10 workers. Such employers do not need to provide social-security benefits. Of 92 million in the formal sector, 49 million, or 53% do not have formal or written contracts with no social security. Most of Kundli’s workers and their parents fall in either or both of these categories, their lives further squeezed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Mostly in their 20s, semi educated and from poor families living marginal rural lives, these workers credit Nodeep Kaur, Shiv Kumar and and their organization, the Mazdoor Adhikar Sangathan (MAS) or Workers’ Rights Association, with recovering past dues from recalcitrant employers, especially after the Covid-19 outbreak.

For their part, industry owners said workers did not appreciate the economic losses caused by the pandemic—India is experiencing its longest economic decline in 23 years—and accused them of extortion.

Educated and sensitive to inequalities in caste and class, they have tried to bring together less-educated rural workers from rural areas.

Nitesh Kumar, 19, a school dropout from Hardoi in Uttar Pradesh who worked as a “helper” at a cosmetic factory, said MAS helped him get Rs 7,000 in back wages. Nadeem, and his two brothers from a landless family worked at a factory making instant noodles and other food, said MAS helped 27 workers get back wages of Rs 180,000. Pinki Devi, a migrant from Bihar, who worked at a utensil factory said MAS “did not even take Re 1 from the Rs 5,953 they helped me get”.

On 12 February, a month after her arrest, and on 15 February, Nodeep Kaur was granted bail by district courts in cases based on two first information reports (FIRs) filed against her by local industries. It is in the third, filed by the police who accused her, Shiv Kumar and their associates of attacking them, that keeps her in a jail in Karnal, 120 km northwest of Delhi.

The daughter of a driver and a farm worker, Nodeep Kaur—who tried and failed to get admission to a BA degree in Delhi university—worked at factories making automotive lights, garments, and masks during the lockdown before she got involved in helping MAS mobilise workers and organise protests.

The son of a landless Dalit farm worker and part-time security guard, Shiv Kumar is a graduate of an industrial training institute, one of hundreds nationwide offering vocational skills, such as welding and plumbing. He worked for two years in the factories of the Kundli Industrial Model Township, an industrial estate on the northern borders of Delhi, before founding MAS in 2018, as an informal collective of workers.

There are contrasting views about Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar, depending on whom you ask. Workers regard them as saviours, industry owners see them as little better than goons, even traitors. What is clear is that they came from an economic and social underclass, and were determined to fight for their legal rights.

‘They Are Anti-National, Anti-Social Elements’

“They are anti-national, anti-social elements,” said Bijendra Grewal, manager of Tops Night Patrolling Private Limited, a private security patrol of 90 men employed by the Kundli Industries Association.

“We have found from Facebook that Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar are not workers,” said Grewal, “but activists who even took part in demonstrations against the government in other instances, such as the protests against the CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act) last year.”

Subhash Gupta, president of the Kundli Industries Association, said they were a “reputed industrial association from an old industrial area”, which despite being “severely affected” by the pandemic, had bused migrant workers home and had paid wages.

“How can these workers claim they will start “revolutionary action” on us over such minor issues?” said Gupta. “Even if you do not get wages for 10-12 days work, does that mean you will surround us in groups of 50?”

Hundreds of young workers are employed in about 1,800 small and medium industrial units, mainly manufacturing auto parts, garments, electronics and household steel in the Kundli industrial township, which adjoins Singhu village on the northern border of Delhi and one of the largest farmers’ protests sites.

When thousands of farmers streamed in from Haryana and Punjab and made camp here, a few hundred metres from the factories of Kundli, the MAS intensified protests—picketing factories, shouting slogans—for wages held back during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

It was two weeks into the agitation on 12 January that the Haryana police registered, in the first of two FIRs filed by local industries, 11 charges, including rioting, “attempting to snatch a carbine gun and a file containing government documents” and use of force, attempt to murder and extortion against Nodeep Kaur and “50-60 unknown” people. If proven, these charges are punishable with 10 years in prison.

‘MAS Did Not Take A Single Rupee From Us’

At Kundli police station, Sub Inspector Shamsher, an officer investigating the 28 December FIR, filed by three men from Tops Night Patrolling Pvt Limited, a security agency hired by the local factories, accused Kaur and Kumar of mobilizing workers to demand money they had not earned.

“These workers work for a few days in the month and then start raising demands for wages by surrounding a factory,” said Singh. “If your domestic worker tries to enter your house forcefully to demand three-four days wages, how would you feel?”

The workers do not see it that way. “It was wrong of the police to term it as extortion,” said Urmilesh Kumar, an 18-year-old Dalit who did not attend school, said the factory where he was a “helper” made the workers regularly sign an attendance register but did not issue payslips. He said they paid up wages for March 2020 only when MAS gathered other workers at its gates. “In exchange for this, MAS did not take a single rupee from us.”

The police filed the third FIR themselves on 12 January, saying they were told about “two-three women and 50-60 men” carrying sticks and sloganeering and trying to break into a metal fabrication factory on plot 349.

As “Inspector Ravi tried to reason with them, a woman challenged the station house officer that since he was the same official who had earlier registered a complaint against them, they would now teach him a lesson” and threatened to kill him, according to the FIR.

The police accuse Nodeep Kaur and those with her of attacking the police with sticks and stones and “trying to snatch a carbine weapon” and “snatching a file containing government papers from head constable Rakesh”.

At this point, said the FIR, three civilians helped the police chase the group and helped a female police officer take Nodeep Kaur into custody. The police submitted medical reports to the Sonipat judicial magistrate’s court listing bruises and abrasions suffered by five police personnel of the Kundli police station.

Police Support Factories, Private Security Teams: Workers

Workers accuse the security agency—hired on police advice—of acting like the owners’ “militia”. They said it frequently deployed “Quick Reaction Teams (QRTs), one of which opened fire during a protest on 28 December 2020.

Gupta, the president of the Kundli Industries Association, acknowledged shots were fired but said they were to deter workers trying to pressure a factory to take back a worker who left after 10 days on the job.

Sahil, a MAS activist who uses one name, said QRTs stopped them from even distributing pamphlets back in 2018 and “physically attacked us” for trying to mobilise workers on 24 May 2020 during the lockdown.

MAS activists said the Association had opposed any attempts to organise workers over two years, but they managed to intensify their work over the two months that the farmers streamed into their vicinity, feeding off their presence.

“On 1 and 3 December after the farmers’ protests, we organised marches marking the Bhopal gas industrial accident (in December 1984) and invited workers to take part in the farmers’ protests,” said Sahil. “And they came in huge numbers.”

It was in this cauldron of resentment that Nodeep Kaur worked, fighting for sums that appeared small by middle-class standards and were not just substantial for workers but their legal right. The Code on Wages, 2019 mandates timely payment of wages and minimum wages to all workers.

On 28 December 2020, workers gathered not 200 m from a farm protest site to demand Rs 5,953 that an employer owed a worker, said Abhishek, who goes by one name, also a MAS activist. “One of the goons in the QRT grabbed Nodeep, while she stood outside the factory gate,” he said. “One of their gunmen fired at us, though no one was injured.”

“When we went to Kundli police station and complained about the violence and use of firearms by the industrialists’ goons, the police refused to respond,” said Abhishek.

On 12 April, when Nodeep Kaur was arrested, a QRT had, activists said, in similar fashion grabbed a worker who tried to deliver a speech at a factory’s gate after clashes.

Other labour organisers described similar private security arrangements and QRTs and bouncers hired by factory owners in townships across Haryana.

“They do not allow us to even distribute pamphlets about worker rights and threaten those who organise with violence,” said Shyambir (he uses one name), a labour organiser with Inquilab Mazdoor Kendra in Manesar, 90 km south of Kundli. “It is the government that is finishing off all collective bargaining rights and shrinking the space for peaceful bargaining.”

Looser Labour Laws And Shrinking Work Options

A BA student who worked to supplement family income—his mother is a farm worker, brother a factory worker—Ankit Kumar described his time at a factory making bulbs and later at one making spices.

“The work atmosphere is such that it is routine for a supervisor to abuse a worker,” said Ankit Kumar. “You are on your feet for 12 hours, you earn Rs 12,000 (per month) after adding overtime, but it ought to be more, as factories pay overtime at the same rate instead of double the hourly rate as they are required to.”

Labour activists blamed the government for deteriorating labour standards. After Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014, Haryana was one of the first states governed by the Bharatiya Janata Party to weaken labour regulations.

To ease labour inspections and compliances, Haryana switched to a “Transparent Inspection Scheme” in June 2016, allowing licenced “non-hazardous factories” with fewer than 50 workers to self certify that they comply with labour laws.

Labour inspectors must give 15-days prior notice to management before inspecting a factory, and that “action be taken on inspection report only as a last resort”.

The suspension of labour laws for April and May 2020 exempted factories from daily and weekly work restriction, although employers were still required to pay overtime wages beyond eight hours of daily work at twice the ordinary hourly rate of Rs 45.40.

Abhishek of the Chattra Ekta Manch (CEM) or Students’ Unity Forum, which organised food for workers during the lockdown and worked in a Kundli factory himself, said no laws appeared to apply inside the factories.

“During the lockdown, they offered no wage support to workers, even as landlords threatened to evict them for not paying rent,” said Kumar. “Forget overtime rates, they did not pay the basic wages, even when the workers returned and asked for the wages owed to them.”

Shiv Kumar was a part of the CEM when he was an ITI trainee, and Abhishek said like him and Nodeep Kaur, several Dalit families who owned little or no land worked in Kundli’s factories but struggled to get minimum wages, decent work or complete their education, to rise above their station in life or simply get by.

Law student Animesh (he uses one name)—the son of a barber and a footwear worker—alleged firms maintained no records, did not pay minimum wages and while some asked for biometrics to enter a factory did not even provide a pay slip.

He said one reason he worked longer hours in the factories was because the government had cut funding for public education and stopped scholarships for other backward castes, of which he was one, after irregularities.

Ankit Kumar, the BA student and part-time worker, said student activists protested in November 2020 when Haryana hiked public medical-college fees by 20 times in one go, from Rs 53,000 to Rs 10,00,000.

“We (CEM) organised a joint protest with MAS at Ambedkar park in Sonipat,” said Ankit Kumar. “How can students like us from poor families afford this? The government is shutting all avenues for us, and at the same time, it is whittling down all labour laws.”

“It is the poor,” said Ankit Kumar, “who will have to raise the demands of the poor.”

It is a lesson Nodeep Kaur learned early in life.

From Mother To Daughter: The Evolution Of Nodeep Kaur

When Nodeep—the fourth of six siblings, including four sisters—was nine, her mother Swaranjit Kaur was a farmhand active in the Punjab Khet Mazdoor Union, a collective of farm workers and farmers in Punjab’s Muktsar district.

Nodeep Kaur was 17 years old and a Punjabi-medium student enrolled in class XII when the family had to move in the middle of her academic year to join their father, who made a living down south in Telangana as a driver and a security guard.

When Nodeep Kaur could not cope with exams in an English-medium school, discontinued her studies and later passed class XII open exams in Punjabi. In 2019, Nodeep Kaur stayed with older sister Rajveer Kaur, who was enrolled in a Delhi University Phd programme in Punjabi.

It was then that she came into contact with student activists in Delhi and Haryana. It was during the lockdown, when her father lost his livelihood for a year, that she began work in Kundli’s factories and got involved with the MAS. “She would share with me on the phone that in the factories, workers like her must stand long hours and could not get even a day’s paid leave,” Rajveer Kaur. “The employers deduct pay if they miss a day’s work. They pay women workers Rs 6000, much below the minimum wage of Rs 9000.”

Swaranjit said because Nodeep Kaur belonged to a family of landless Dalits the farm unions did not rally around her—even though elder sister Rajveer worked hard to get public attention—until tweets by Canadian poet Rupi Kaur and Harris gained international attention.

Rajveer described her younger sister as “bold, confident, and inventive”.

“Nodeep has always been fiery and fearless,” said Rajveer Kaur. “Though her studies were disrupted because of our family’s move to Makhtal in Telangana, she tried to support my studies.”

“When I would return to our village while studying for my BA at the government college in Ludhiana, the bus would not go till our village,” recalled Rajveer Kaur. Nodeep learned to ride a motorcycle to pick and drop her sister.

“She always acts like she can deal with just anything,” said Rajveer Kaur, “whether her motorcycle breaks down or any other crisis.”

She said social inequalities and injustice was a part of their lives. “We are directly affected by them,” said Rajveer Kaur. “This is why our parents have taught us to call out injustice. My mother always says, we must call out injustices, with no compromises.”

Those injustices were evident to Nodeep Kaur at her workplace in Kundli, as the central government began to reform labour laws nationwide.

Farm, Labour Laws And The Power Of The Collective

Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar, said their colleagues, told them the repeal of new farm laws—which farmers contend favour companies to the detriment of farmers with medium and small holdings—were not dissimilar to the demand by industrial workers to repeal four new labour laws.

Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar believed the labour codes would increase work hours and the potential for arbitrary dismissal, reduce wages, the right to unionise and protection against workplace injuries.

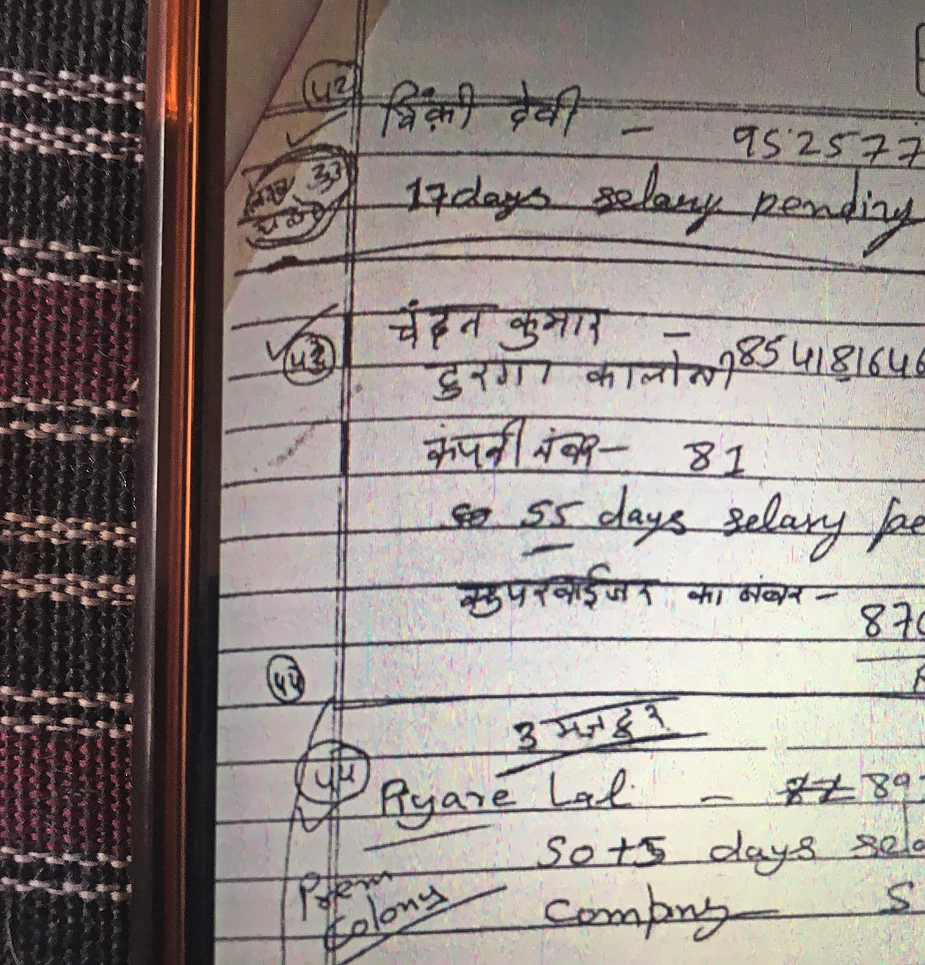

Every worker in the area narrated current workplace woes, from short or delayed payments and manipulation of or refusal by factories to accept their own proof-of-work documents.

Vijay Kumar, a tailor making school tee shirts, said the company at which he worked, Dev India Enterprises, promised him wages in cash every 15 days, but did not pay ever after 30. “They said their payments were stuck because schools were closed because of the pandemic,” said Vijay Kumar. “I have photos of their attendance register, but they won’t accept that as proof of my work now.”

Labour inspector for Kundli Sunil Rathee acknowledged complaints and said his department tried to resolve them. The district labour commissioner, Hari Sharma, did not respond to Article 14’s request for comment.

When Vijay Kumar asked for his dues of Rs 12,000, he said, he was told to come to a new site to which the factory had moved. “They said, ‘we can consider payment if you come work here for a month’. Why should I work there when they owe me Rs 12,000?”

Devendra Kumar, a manager at the company, denied the allegations of Vijay Kumar and other workers, who alleged being similarly shortchanged. “We had just 15 workers working for us last year, and we have paid all of them full wages.”

All the workers Article 14 spoke to said MAS had either pressured companies to pay up or at least tried, which was good enough for most of them.

Utensil factory worker Pinki Devi said MAS gave her and her spouse a letter on the organisation’s letterhead, demanding the company pay them the Rs 5,953 owed to each of them.

“The company official got angry and asked us why we went to MAS,” said Pinki Devi. “But then, they paid my wages.” She and other workers said MAS protests and pressure led to payments due from even a year ago in a number of companies.

Nadeem, the noodle-factory worker quoted previously, said workers had no choice but to organize. “When factories do not even show us as workers (in their records), our only proof of our work is the co-workers alongside whom we have worked,” he said. “Why have police filed criminal cases against our colleagues? We were only asking for our rights, is it not?”

Why The Government Fears Otherwise Invisible Workers

The genesis of events that led to Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar’s arrests, as we said before, lay in India’s pandemic-induced lockdown, described as one of the “most stringent” in the world and the “least generous” in providing relief.

While the government shut down almost all commercial establishments and movement, its initial relief package did not contain any specific measures for migrant workers. Dismissing a petition to ensure wages to migrant workers, the Supreme Court said: “If they are being provided food, why do they need money for meals?” It protected private employers against any action for not paying their workers through the lockdown.

The 68-day lockdown triggered an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. In several cities, workers stranded without food and money and facing travel restrictions clashed with security personnel, and millions tried to walk back to their hometowns and villages despite travel restrictions.

While the condition of workers became known to middle-class India, their lives remained as invisible as ever, revealing themselves only around times of tension.

That indeed is how Shiv Kumar’s difficult life came to attention, after his incarceration. His father Rajbir said Shiv Kumar Kumar was one of five children, one of whom had a mental disability, and his wife had a mental illness.

Rajbir said he had educated Shiv Kumar at privately run village schools—in class X, despite four surgeries, he lost eyesight in one eye—before enrolling him at the Sonipat ITI, where he learned to handle tools.

Naresh Kumar, one of Shiv Kumar’s peers at the CEM, described him as a “quiet bookworm”, a young man with tenacity who wants to study further. “He reads a lot of current affairs in Hindu and publishes and edits a quarterly called Abhiyaan (The Movement),” said Naresh Kumar.

This is not Shiv Kumar’s first brush with jail. In 2015, he spent 16 days in Sonipat prison with 38 others after protesting how school’s denied admissions to children of low-income families in violation of the right-to-education law. Inside prison, said Jasminder, the colleague from CEM, prison officials singled out Shiv Kumar for cleaning work because he was a Dalit.

Rajbir is distressed that he had not been able to speak to his son even four weeks after arrest, which he should have been able to.

“The police have not allowed me to speak to him even on the phone,” said Rajbir, visibly distraught. “I do not know his condition.” He can now meet his son after the High Court’s intervention.

Nodeep Kaur’s mother Swaranjit said she feared for her daughter’s safety in police custody.

“My daughter knows her rights, but she belongs to a family of labourers,” said Swaranjit. “The government wishes to suppress her voice because they think if they do not do so now, more like her will raise their voices.”