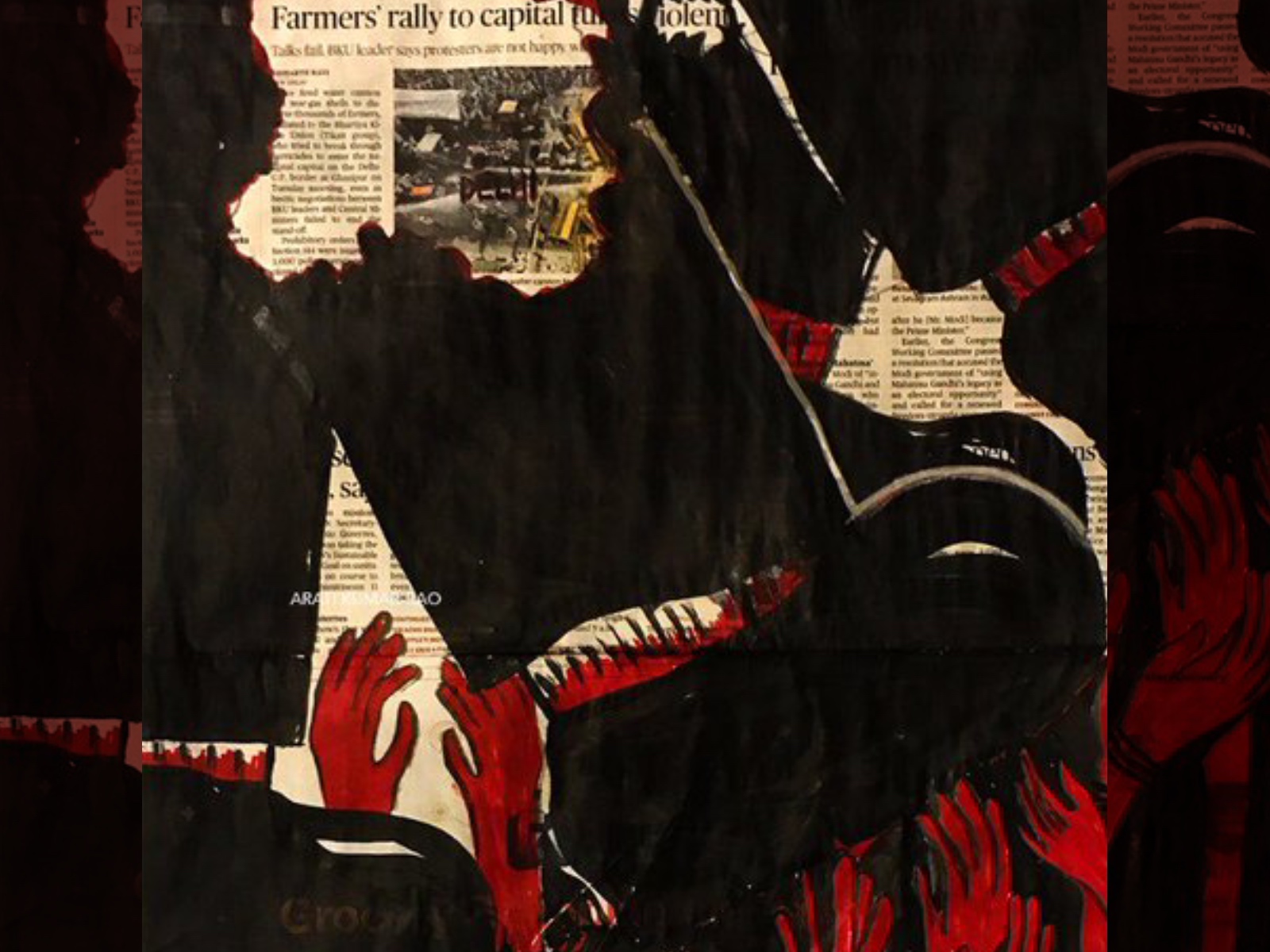

In 2019, Karthika Naïr, who considers herself a political poet (or rather: “how can literature not be political?”) would be moved to write on Shaheen Bagh, when in December 2019, a handful of Muslim women came out of their homes in Delhi to protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act, and resolved not to move before they were heard. Shaheen Bagh was also a peaceful resistance to and against violence: the violence to which Muslims and women have been subjected for so long in India; the violence unleashed at the Jamia Millia University campus a few days earlier, and the constant threat of violence (by the police and by right-wing “goons”) to which the protestors were subjected during the one-hundred days during which the sit-in lasted. The “dogs of carnage” summoned by Karthika Naïr in her ghazal, eventually broke loose, unleashing terror in the streets of Delhi. But what happened at Shaheen Bagh is and must be remembered. And the task of the poet is also to make sure that these voices continue to be heard.

In the following interview conducted over Skype, and revised over email in September 2020, Laetitia Zecchini and Karthika Naïr talk of Shaheen Bagh and of Naïr’s poem “Ghazal: India’s Season of Dissent”; of the activism of Indian writers and artists; of the politics of literature; of the relevance of poetry to protest movements and resistance struggles; of how literary texts can “respond” to violence, grief and pain. Here is an excerpt from the interview.

LZ: You’ve got this wonderful line in the poem, “Poetry, once more, stands tall.”

LZ: You’ve got this wonderful line in the poem, “Poetry, once more, stands tall.”

KN: Yes, and I think what has got forgotten is that it’s an oral form, perhaps the oral form par excellence, and that it has been part of many, many, great movements. You see, they were all outliers, the Sufi, bhakti poets, freedom fighters. You take any regional, national, religious movement of dissent or reform, poetry’s been there. So here, at Shaheen Bagh, I think we were seeing that poetry came out of the books/ notebooks, came out of this misconception that it’s an elitist art and took its place on the street… A lot of the poets I quoted, you know, Aamir Aziz, Kausar Munir, Varun Grover, Bisaralli were all out there, in Delhi, Bombay, smaller cities, in the streets, on the platforms, reciting, chanting, improvising. And that’s again a tradition which it was high time we brought back. And it’s just fantastic that it was their words that were being echoed, and translated across the country. “Kaagaz nahi dikhayenge” went into English, Tamil and many other languages. That was quite inspiring from far away. Have you seen that video where Kausar Munir speaks in three different languages, Hindi, Urdu, English, in the same poem, and also talks about her grandfather who made that choice to stay on in India after Partition?1 The case she makes is: “How do you divide or even define an identity.”

And I think Faiz’s “Hum dekhenge” is the finest example of something that crosses continents, borders, languages. The funniest part actually, and it’s bitter, bitter humor, is when the dead Faiz gets involved in a case of “anti-Hindu sentiments.” Then you know that the country is really in a ridiculous state.2

LZ: Perhaps we can explain briefly the intertextual fabric of this poem. So you have the first words from the Preamble to the Constitution of India (“We the People of India …”) that was meant to spell out the principles of justice, fraternity and liberty on which the Constitution was laid; you spoke about Faiz and his iconic poem “Hum dekhenge” (“We shall see”); lines from a poem Aamir Aziz released after the brutal attacks on the Jamia Millia and JNU Campus, “sab yaad rakha jayega” ( We will remember it all3); lines of another poem which became an anthem of dissent from lyricist and actor Varun Grover, “kaagaz nahi dikhayenge” (the—NRC—papers we won’t show). And you also quote the name of Kannada poet Siraj Bisarelli, whose recitation of an anti-CAA poem (echoing and inverting Varun Grover’s earlier text) “When will you show your papers,” led to his arrest. Are there any other references or “echoes” you would like to highlight?

KN: Yes. The third couplet names some of the far-flung or smaller cities, states (as well as Kolkata, which has its own proud tradition of dissent) that don’t always get talked about in national media for the right reasons, but were all chronicled in the press as having had widespread, sustained movements of resistance. And the fourth couplet references an incident in Dibrugarh (Assam) where, as police forces came to lathi-charge them, protesting anti-CAA students sang the national anthem, Jana Gana Mana (I think Tagore would have approved!)

LZ: You also direct the poem towards the future, with the wonderful evocation of the little baby girl Umme Habeeba,4 “our oldest, finest reason for dissent” you write, and perhaps our “finest reason for hope?” Barely 6 months ago, I imagine that so many people in India (and abroad) thought that things would change, that there was reason for hope. And then came the lockdown, and now the government’s criminalization of so many of those who took part in these peaceful protests…

KN: Yes, in that last couplet, it was also an exhortation to myself to remember that we are not just fighting for today, we are fighting for tomorrow. Now it’s very tempting to think of what might have happened, if Covid hadn’t exploded on the scene. In countries across the world, the one force that this pandemic has helped is the force of absolutism and authoritarianism. It has just made every single abuse secondary in terms of attention and coverage, and also in terms of priority in people’s minds. And that’s true across the world. Individual rights, freedom of press, the rights of the most fragile sections of society have suffered during the lockdown.

LZ: I wanted to quote the words of writer Githa Hariharan, who is also the co-founder of this extraordinary platform, The Indian Writers’ Forum, to which you have contributed.5 In a text written for the 3rd anniversary of Gauri Lankesh’s brutal murder, she paints a very dark picture of the situation in India today, with the growing list of political prisoners languishing in prison without trial, the attacks on Muslims, minorities, academics, students; the charges of sedition, conspiracy, contempt of court or “unlawful activities” levelled at many citizens. And yet, she says “we still have voices that speak up”: “If we speak, Gauri will continue to speak…They cannot silence us all.”

KN: I really think The Indian Writers Forum has been doing a wonderful job for so many years as a sentinel. It reminds me of that old saying about those who stay awake, so others can sleep in peace. Now I don’t think anyone of us can sleep in peace right now, but the IWF has been there as the eyes in the dark for so long. And they are putting what they see in the dark out there. And that’s precious. I think we also have to remember that it’s extremely fragile… Remember that whether through fiscal legislation, or through other means, so many NGOs in India are under increasing threat. And for years I was not able to give a donation to IWF because I am a foreign national. The irony of it is that political parties can receive unlimited foreign funding without any examination or questioning, but NGOs are suspect. So even when you are not hounding an organization actively, you are cutting off its blood supply. In other words, supporting something like IWF is more and more vital.

More generally, I think, yes, we have to resist and speak up a long time before we are on our knees. There is so much that we have to be constantly vigilant about. Here as well (i.e. in France). A few months ago, I heard someone who is a leftist and an activist say that he was going to vote Marine Le Pen in the next election, because he said, “it can’t get much worse.” And I said, it can get much worse. You are a straight, white man in your 70s. Yes, things are going to be ok for you on a quotidian level. But for anybody who is different in any way, in terms of race, in terms of sexuality, in terms of language, in terms of religion, in terms of dissent or mobility, no it is not going to be ok. The alternative cannot be the Marine Le Pens of the world, because India is standing testimony to how little it takes to dismantle a democracy. 5 years! When you had 65 years behind you… What I mean is all you need is the wrong regime in power, in both houses of the Parliament, with enough clout to purchase or threaten free press. No country is invulnerable in its democratic or republican principles.

1. The poem “Woh Kaghaz kahan se laaon” (Where do I find the Documents) penned by lyricist Kaunsar Munir is available on Scroll.in. February 28, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

2. When the IIT Kanpur faculty and students sang “hum dekhenge” to protest and show solidarity with the students of Jamia Millia Islamia, other faculty members came together to file a complaint. The Wire Staff, 2020. “IIT Kanpur Panel Says Reciting Faiz’ ‘Hum Dekhenge’ was ‘unsuitable to Time, Place.” The Wire, March 16. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

3. “Everything will be remembered / Kill us, we will become ghosts / and write of your killings… We will speak so loudly that even the deaf will hear / We will write so clearly that even the blind will read / You write injustice on the Earth / We will write revolution in the sky.”

4. Umme Habeeba was described by the press as the youngest of all “protesters” present at Shaheen Bagh. Barely a month old, the baby girl was brought to the protests by her mother. She is mentioned in Samrat Chakrabarti. 2019. “Shaheen Bagh Heralds a New Year with Songs of Azaadi.” The Wire, December 31. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

5. See “‘We are Talking of More than Writers’ Rights, We are Talking about Letting People Live’: An Interview with Githa Hariharan,” art.cit.