If our family stories shape us, what happens when we learn those stories were never true? Who do we become when we shed our illusions about the past?

Maya Shanbhag Lang grew up idolising her brilliant mother, an accomplished physician who immigrated to the United States from India and completed her residency all while raising her children and keeping a traditional Indian home. Maya’s mother had always been a source of support—until Maya became a mother herself. Then the parent who had once been so capable and attentive became suddenly and inexplicably unavailable. Struggling to understand this abrupt change while raising her own young child, Maya searches for answers and soon learns that her mother is living with Alzheimer’s.

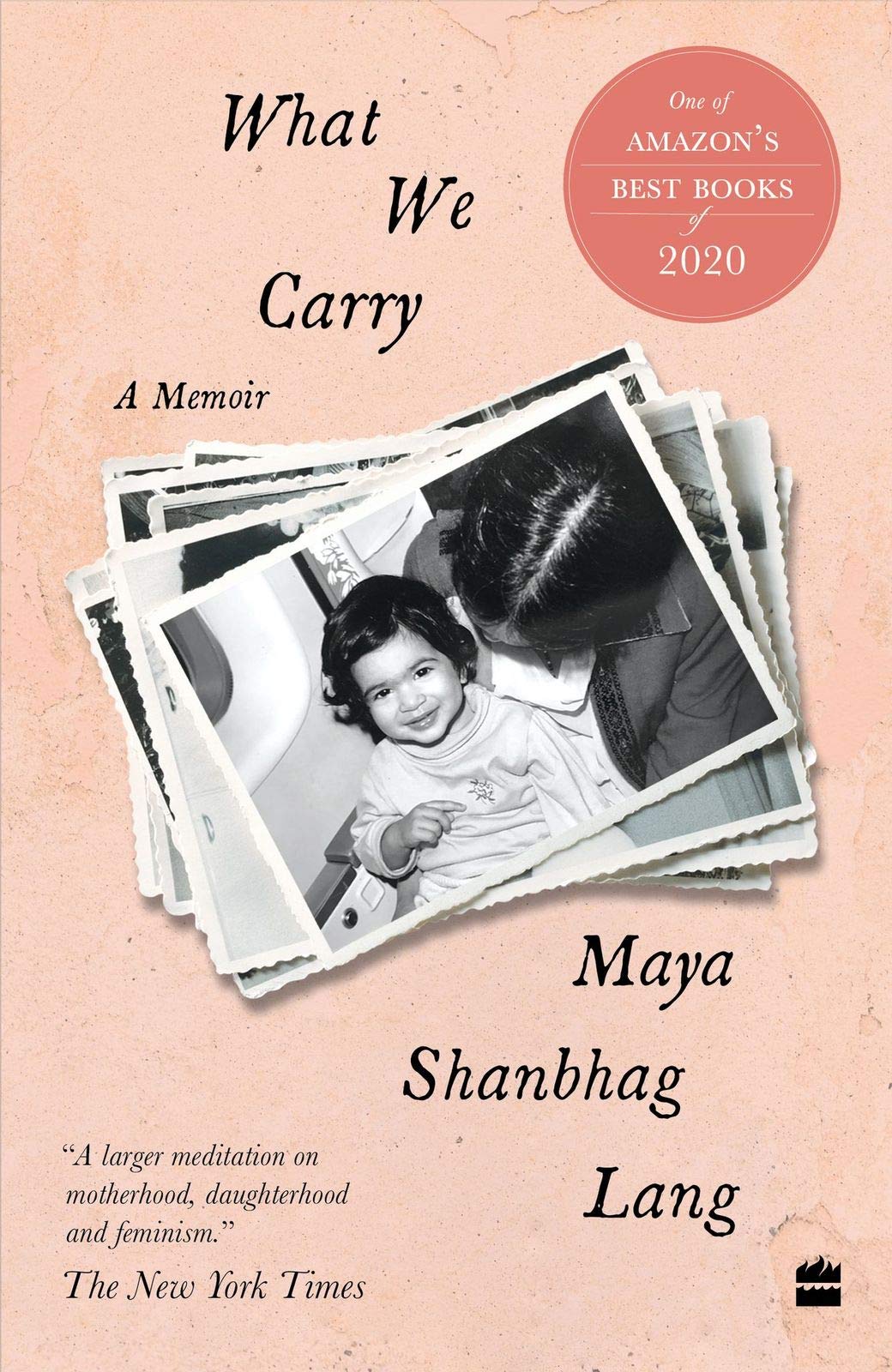

What We Carry is a memoir about mothers and daughters, lies and truths, receiving and giving care, and how we cannot grow up until we fully understand the people who raised us. It is a beautiful examination of the weight we shoulder as women and an exploration of how to finally set our burdens down.

Mom, you once told me a story “I say on a walk one day. “You said your mom told it to you. It was a myth about a woman in a river, holding a child in her arms—”

“Oh!” She stops abruptly and turns to me. “You remember that? You have such a good memory. I have not thought of that story in years!”

“I tried to look it up. I didn’t know if it was a myth or if it was based on a Hindu parable of some kind. I can’t find anything on it.”

“Hmm.”

“Is there any chance Agi invented it?”

“She was not a writer, if that’s what you mean. You are the only storyteller in the family” She chuckles.

“What really gets me is the ending. Or lack of ending, I should say.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, we don’t know what the woman in the river chooses.”

“Of course we do. She lets go of her child.”

She says this so matter-of-factly I think I’ve imagined it.

“What?” I laugh. “Mom, that’s not what happens. The woman stands there. You said . . . you said we can’t know what she chooses until we are in the river ourselves.”

“Is that what I said?” She looks bemused. “No, the way my mother told it is that the woman lets go.” Seeing my shocked expression, her features soften. “I must have changed it to protect you. Perhaps it seemed too harsh.”

“So… the story just ends like that? With her letting go of her baby?”

She shrugs. “Indian stories, you know. They can be quite strange.”

We walk for a few minutes, my mom sniffling and snorting and humming in her off-key way. My question feels even more pressing now.

“The thing is, how does the woman live with herself?”

“What woman?” My mom has forgotten our conversation. I take her through it again, this time not sharing how she revised the story.

“Yes, yes,” she says. “The woman in the river. What is your question?”

“Well, I mean, how does she do it? How does she let go?”

“She just does.”

“Come on, Mom, it can’t be that simple. She must regret it, right? Does she reach for her child, realizing her mistake? Does she spend the rest of her life filled with regret?”

“No.”

“But Mom —”

“She has let go. That is the point.”

“That doesn’t answer the question of how.”

“You are asking the wrong question.”

“I am?” I don’t even know what I’m asking anymore.

“You imagine the woman still holding on to the child after she has let go. That is your error. The story is not about her letting go.”

“It isn’t?”

“The story is about the woman choosing herself. Once she makes that choice, everything follows.”

Oh. The way she puts it makes the story a positive one, not a of loss and anguish, but one of hope. A story with a future tense. It occurs to me how right my mother is.

When I glance up, I see that she is several feet ahead. I hurry to catch up. “Do you think it’s possible? For a woman to choose herself? Do you think… do you think she ends up happy?”

“Of course. Why wouldn’t she?”

“But what about the child who drowns?”

“Who said anything about him drowning?”

“You’re saying he lives?” “You never know in Indian myths. Perhaps a bird comes and lifts him away.”

Her mouth twitches. We laugh. Soon we are laughing harder than we should, harder than the situation warrants. “Can you imagine? The baby held in the bird’s beak?” It sets us off, howling, maybe because it’s so exactly in keeping with Indian myths, or maybe because it feels so good to laugh that we don’t want to stop. And then the deer in the forest would feed him!”

“And provide him shelter!”

“And he would grow up to be king!”

“Of course!”

We laugh so hard we wipe our tears.

The woman chooses herself.

Once she makes that choice, everything follows.

Could it really be that simple?