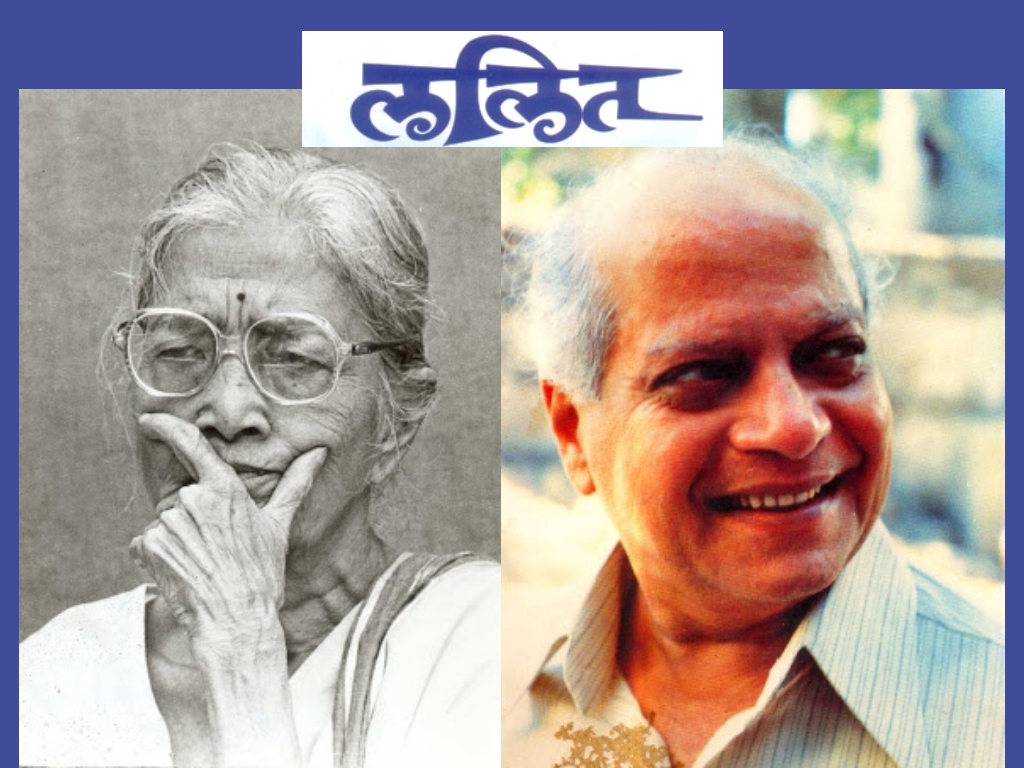

Arguably the foremost female writer in Marathi, Durga Narayan Bhagwat was a scholar, socialist and writer. She studied Sanskrit and Buddhist literature and even spent a few years in the jungles of Madhya Pradesh to study tribal life. Prominent writer Jaywant Dalwi interviewed Bhagwat for the Marathi journal Lalit in 1970. The interview has been translated into English by playwright Chandrashekar Phansalkar.

The following is an excerpt from their conversation.

Jayant Dalwi (JD): You wandered in these far off jungles at a young age; and you were a woman. Did you not feel insecure and vulnerable?

Durga Bhagwat (DB): Initially I did, somewhat. But the constant awareness of my purpose of being there; which was pursuit of knowledge; always drove away the fear and the worry. And as time passed I realised that those people living in jungles were an innocent and upright lot. This rid me of my fears completely.

JD: As a woman, did you have any trouble from the locals?

DB: Never! On the contrary, it was a man from the city who tried to be uncivil with me once. He was a forest officer. But when I threatened to report him to the governor, he got scared and ran away.

JD: It is really nothing short of a miracle that you lived in those strange, unfamiliar jungles for such a long time alone as a young woman.

DB: It was the era of Gandhiji and people revered his values. Almost all the young people of my generation were inspired by him. I always had the confidence and courage that I could overcome any danger that befell me. Of course I used to be cautious as well.

JD: What do you mean by the word cautious?

DB: There is an instinctive and intuitive sense of self protection in a woman which makes her aware and cautious of potentially insecure situations. I always slept lightly at night.

JD: Didn’t it tire you out?

DB: Never! On the contrary, I experienced that when one is nestled in Nature’s shelter, the clean air and placid surroundings keep energizing one constantly and one does not actually need too much of a rest. Furthermore I mainly worked at nights.

JD: Why?

DB: Because it used to be the only free time that the tribals had. They are completely occupied in their work and chores during the day. It is only at night that they become free when they celebrate by singing and dancing.

JD: You did not have any problem communicating with them?

DB: Not much. I had learnt Hindi, Gujrathi and Kannada, apart from our own Marathi. This made it easy for me to understand their tongue which used to be a blend of these languages. For instance, the tribal language called Chhattisgarhi is a hybrid of Hindi and Marathi. They say “तोला”instead of “तला” and “मोला”instead of “मला”. The Gondi language had more kannad in it.

JD: Did the poverty those people lived in ever become a threat?

DB: Never! In fact, their houses did not have doors. They did not know what a ‘lock’ was. They were very honest people. They never lied. At least that was the case when I visited them. They would occasionally kill each other in a fit of intense anger. But then they confessed they did it and for a particular reason. They never hide anything. If you find thieves and liars amongst them today, I am more than sure that they have been corrupted by people like us from cities! They really were a simple and virtuous lot when I visited them.

JD: You had studied Hinduism, Buddhism. You were not satisfied with what you got there. You therefore, went and lived with these so called “backward” people on purpose. Did you find what you were looking for? And what was that?

DB: I found real satisfaction. And strength. Those people tore away the “upper class” veils over my eyes and presented me with a fascinatingly pristine world.

JD: Elaborate.

DB: The poverty they lived in was really terrible. Sometimes, they did not get anything to eat for days on end. Even the smell of a fistful of rice and dal boiling was like having a feast. In such hardship, they had in them the spirit to sing and dance; that too with such unbridled happiness. Not even a hint of misery there! I found that captivating. I realised my mind had stopped hurting. The inner turmoil and torture had calmed down. I felt it was enough to just exist as a human being to be happy. You asked me what it was that I found there. I found fellow human beings. And realised that they were the true citizens of this country. Citizens full of basic wisdom and an inherently vital philosophy that did not require them to be formally educated.

JD: What were the unique things you found in the way these adivasis lived?

DB: Most of these adivasis have the custom of what we call a love-marriage. A couple would know and love each other before tying the knot. When they do marry, it is the bridegroom who gives a dowry to the bride… They have a custom of sacrificing a pig to the God in their ceremonies…their women cannot participate in the ritual of worship…so on and so forth.

JD: And anything different, uncommon about the way those people behaved? Any unique characteristics about their mental make-up?

DB: Humour! These people have a great sense of humour. It is inherent in them. Their everyday chat is full of natural humour. There is nothing contrived about it.

JD: Any example of this humour?

DB: Once a woman’s husband was lying down on the ground in the searing April heat. He slept facing the Sun. Looking at him the woman said to me” See, how that ass is scalding himself in the sun.”

I said, “Why did you marry an ass when you had a wide choice? You could have loved someone else and married him.”

The woman replied, “No. You don’t get to choose a man as your lover here. There are none. A woman can choose from an ass, a bull, a horse or a bison. But a man? Never! I had to choose one of these beasts; I chose an ass.” (Smiles)

JD: How come they have such a good sense of humour?

DB: I feel that the lower one descends the social ladder, the brighter is the sense of humour one encounters. These poor and needy people have always found a means of survival in humour. We know how pure and natural the humour of a Songadya (Folk clown) is. It is much more spontaneous than the urban upper class humour. Look at the humour in what Bahinabai, Laxmibai wrote. Doesn’t it feel more genuine, more inartificial? The Gonds for instance, love making puns when they talk and they are very good at it.

The upper class urban humour is more satirical in nature. It has the quality of pinching if not hurting others. It hates to laugh at itself. It comes forth more like a weapon. A weapon brings with it a sense of power. And power corrupts humour like it does everything else. It kills the simplicity and innocence in humour.