Anita Anand’s book weaves a personal and social account of Afghanistan, written as a result of her travels and work in and around Kabul. The extracts below discuss the history of Bamiyan and its cultural significance, and the devastating psychological and physical damage wreaked on the country by the American occupation.

Women Unlimited: New Delhi, 2016

Women Unlimited: New Delhi, 2016

Bamiyan and the Buddhas

Bamiyan lies about 240 kms north-west of Kabul and was the site of an early Hindu–Buddhist monastery from which Bamiyan takes its name (Sanskrit varmayana, “coloured”).

The Bamiyan valley marked the westerly-most point of Buddhist expansion and was a crucial hub of trade for much of the last millennium. It was a place where east met west, and its archaeology reveals a blend of Greek, Turkish, Persian, Chinese, and Indian influences, found nowhere else in the world.

Situated on the ancient Silk Route, the town was a key location as all trade between China and the Middle East passed through it. The Hunas made it their capital in the fifth century. The Shar-i-Zohak mound, ten miles south of the valley, is the site of a citadel that guarded the city, and the ruins of an acropolis were found there as recently as the 1990s.

Many statues of the Buddha were carved on the sides of the cliffs facing Bamiyan city. Three colossal statues were carved 4,000 ft. apart on the cliff face of a mountain. One of them was 175 ft. (53 m) high standing statue of Buddha, the world’s tallest. According to sources, the ancient statue was carved during the Kushan period in the fifth century. It is said that at one time, two thousand monks meditated in caves among the sandstone cliffs.

Further enhancing the cultural capital of the city, the oldest oil painting was discovered in Bamiyan in 2008 in the caves behind the partially destroyed colossal statues. Scientists from the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility have confirmed that the oil paintings, probably of either walnut or poppy seed oil, are present in 12 of the 50 caves dating from the fifth to ninth centuries. The murals typically have a white base layer of a lead compound, followed by an upper layer of natural or artificial pigments mixed with either resins or walnut or poppy seed drying oils. Possibly, the paintings may be the work of artists who travelled on the Silk Road.

The caves at the base of these statues were used by the Taliban for storing weapons. After the Taliban were driven from the region, civilians made their homes in the caves. Recently, Afghan refugees escaped the persecution of the Taliban regime by hiding in these caves. These refugees discovered a fantastic collection of Buddhist statues as well as jars holding more than ten thousand fragments of ancient Buddhist manuscripts, a large part of which is now included in the Schøyen Collection.

The Schøyen Collection is the largest private manuscript collection in the world, located mostly in Oslo and London. Formed in the 20th century by Martin Schøyen, it comprises manuscripts of global provenance, spanning 5,000 years of history. It contains more than 13,000 manuscript items; the oldest book is about 5,300 years old. There are manuscripts from 134 different countries and territories, representing 120 distinct languages. This discovery from Bamiyan has created a sensation among scholars, and the find has been compared with the discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls.

Bamiyan, a small town with a bazaar at its centre, has no infrastructure in terms of electricity, gas, or water supplies. For decades, it has been the centre of combat between zealous Taliban forces and the anti-Taliban alliance—mainly Hizb-iWahdat—amid clashes among the warlords of local militia.

Mirwais, Abdul, and I walk down the one-road market, looking at the shops with local goods. My interest is the antique shop which Abdul directs us to. It is called shop number 368. The shopkeeper is kind and opens up the rugs and kilims for me. Mirwais and Abdul admire the jewellery. I buy three rugs and some jewellery, including rings for Abdul and Mirwais.

We drive out to the Women’s Garden, a space organised by the NGO, Parsa. Besides the Garden, there is a small guest house with a restaurant and a beautiful garden with flowers, vegetables, and stunning poplars.

We order lunch and, while it is being prepared, walk around the garden. Mirwais and I take photographs. We then sit under the poplar trees and listen to Abdul’s story. He points out—in the distance—to where he was shot by the Taliban and narrowly escaped. He tells us about his family and his job as a driver which is only for the non-winter months in Bamiyan. The hotel closes down as Hiromi moves to Kabul to avoid the very bitter winter.

2012–2013: The Continuing War and Insurgency

The insurgency and war in Afghanistan continue. Many observers now believe that future peace in Afghanistan can only come if the government in Kabul negotiates with the Taliban. According to news agency reports, the Taliban announcement to open an office in Qatar in June 2013 was seen as a positive step in those negotiations, but mistrust on both sides remained high. Hopes for peace talks were equally high early in 2012 before the Taliban in Afghanistan announced, in a strongly-worded statement in March of that year, that they were suspending preliminary peace negotiations with the US.

There have been numerous Taliban attacks on Kabul in the past two years and, in September 2012, the group carried out a high profile raid on NATO’s Camp Bastion base. In the same month, the US military handed over control of the controversial Bagram prison—housing more than 3,000 Taliban fighters and terrorism suspects—to the Afghan authorities.

In recent years, the Taliban have also relied increasingly on roadside bombs as a means of fighting NATO and Afghan forces. The exact number of people killed by these bombs is difficult to calculate, but the interior ministry says they were responsible for killing most of the 1,800 Afghan national police personnel who died in 2012. During the same time period, estimates suggest, about 900 Afghan National Army soldiers were killed by roadside bombs.

In August 2013, the Afghan government-backed High Peace Council opposed “tough pre-conditions” for talks with the Taliban and urged the government and the Taliban to show flexibility in order to bring the stalled Qatar process back on track.

The remarks came weeks after the closure of the Taliban office in Qatar, following a row with the Afghan government over the use of the flag, and a plaque bearing the name of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan—the name the Taliban used when they were in power.

President Hamid Karzai refused to send the peace council members to Qatar as he considered that the flag and the plaque promoted the office as an embassy of a government-in-exile. The Taliban closed the office following the Qatari officials’ decision to lower the flag and remove the signboard of the Islamic Emirate. The top Taliban leadership said they would not talk in Qatar until they were allowed to display the flag and plaque at the office once again, a Taliban official told The Express Tribune.

In order to revive the dialogue process, the Afghan High Peace Council called upon the Afghan government and the Taliban to give up these conditions before the talks begin. They mentioned they were in touch with Pakistan and it wanted to free all Taliban prisoners, including (Mullah Omar’s deputy) Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar.

Afghans attached high hopes to the visit of the Afghan President, Hamid Karzai to Islamabad, as the talks could help in the reconciliation process. The Afghan government is aware and openly says that Pakistan has a key role in the Afghan peace process. The Taliban leadership is based in Pakistan, and the Afghans want it to extend support to the peace process and facilitate direct contact between the peace council and authorised Taliban representatives. They also want Pakistan to provide safe passage to Taliban leaders who are prepared to engage the Afghan government in direct negotiations.

In the meanwhile, Afghanistan continued to face challenges due to the conflict. In 2012, according to official statistics, 94,299 Afghans had been internally displaced by conflict and 32,490 of them were living in the 55 Kabul informal settlements; 9,851 people were newly registered as internally displaced. This figure increased substantially in 2013—a total of 502,628 Afghans were internally displaced by conflict and 2.5 million registered Afghans were forced to move to neighbouring countries.

War, displacement and migration bring—besides the physical suffering—an accompanying burden of mental challenges, which are often ignored. In October 2013, Joel Brinkley, professor of journalism at Stanford University and former foreign correspondent for The New York Times, reported that Afghan soldiers shot and killed at least 135 of the American servicemen who were training them over the past five years. In 2012, the United States Agency for International Development interviewed large numbers of young people in Afghanistan and found them generally to be “disenfranchised, unskilled, uneducated, and neglected”. These people, it added, “are most susceptible to joining the insurgency”.

But, says Brinkley, multiple medical studies over the past nine years indicate that these disaffected young people are less likely to volunteer for the insurgency than they are to join the tens of millions of Afghans who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, clinical depression, perpetual deep anxiety, and other debilitating trauma-related mental illnesses that are rife in the country. And these mental illnesses can sometimes lead to irrational, violent acts—like killing your trainers.

This trauma, Brinkley argues, could be thoroughly undercutting the strategies of the United States and its allies in Afghanistan, even as western forces are leaving. But the American military and policy-making community was not even aware of the problem, therefore little was being done to address it or compensate for it.

Brinkley interviewed Air Force Col. Erik Goepner who, when stationed in Afghanistan, said he learnt that these environmental factors can lead to severe mental illness—even though to this day, American servicemen receive no training on psychological issues before leaving for Afghanistan. “As an American military commander, you want to win,” Goepner noted in the interview. To him, it was clear that even after a decade of warfare, there was to be no “decisive win. And so you look back and ask: Why isn’t it going the way I want it to?”

In part, to help find the answer, Goepner began working “with a lot of Afghans” and came away with “the idea that something was going on in the mental head space”. Psychology was not among his areas of expertise but, over time, he read a number of psychological studies and learnt that more than half of Afghans suffer from clinical PTSD. And in some studies, the number afflicted with severe anxiety and clinical depression exceeded 70 per cent.

American political and military leaders never talked about this as part of the challenges they face in Afghanistan. In fact, said Paul Pillar, who was the CIA’s national intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia for several years, “I do not have any recollection of that; I do not recall seeing any reports on that.”

Denial is not only the purview of the Americans and military leaders. Social scientist Anna Maria Cardinalli, who worked for the military in Afghanistan for several months, points out how average Afghans greet visitors with “a vacant and unsettled stare in the eyes”. Cardinalli was the lead researcher for a Pentagon study on paedophilia in Afghanistan. Over generations, older men have taken tens of thousands of little boys as lovers, an Afghan custom, often leaving the boys with severe emotional, and perhaps even physical, wounds. The children remain untreated because mental health care is virtually non-existent, and parents are generally ashamed to seek treatment for physical wounds.

Boys, girls, teenagers, adult men and women, and the elderly—all are beaten down, battered, and bruised. The years of war ripped apart not just the physical infrastructure, the psychological structure of Afghan society has also been devastated.

All of this adds to the toxic mix of dysfunction. One critical result of this is that most Afghan civilians want nothing at all to do with the Afghan government or the western military forces supporting it—even though their support “is the critical element” of counter-insurgency strategy, says Col. Erik Goepner.

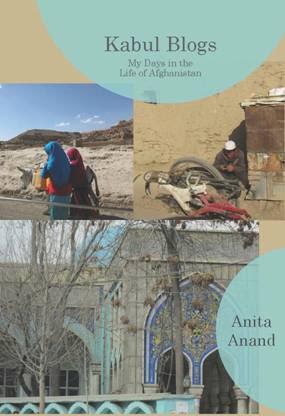

Kabul Blogs: My Days in the Life of Afghanistan is published by Women Unlimited: New Delhi, 2016.