It’s hard to steal focus from the student community these days. Especially on a day like today, when the names Anirban, Umar and Kanhaiya continue to dominate headlines. Before a JNU students’ protest march demanding the release of Umar Khalid and Anirban Bhattacharya, JNU Student’s Union Vice President Shehla Rashid described the student arrests as a “witch-hunt of students”.

The hunt isn’t restricted to students anymore. The march was also to demand the release of SAR Geelani, an ex- Delhi University professor, accused in the 2001 Parliament attack but acquitted by the Delhi High Court; then arrested again in February 2016 on sedition charges. At the very least, Geelani’s supporters would describe his detention in such terms as well. Geelani wasn’t the only one ‘pulled up’ for voicing his views on Kashmiri self-determination; police complaints have been filed against Nivedita Menon, a Professor of Political and Feminist theory from JNU, for saying during a lecture that India has illegally occupied parts of Kashmir.

Comments on Kashmir’s self-determination have always drawn the State’s ire. But months before they were made in JNU, some academics reported a feeling of insecurity – that they were being watched, their words noted for future vilification. Those who, like Menon, favour free speech and liberal thought (especially within the confines of the University campus) worry that a freshly pronounced hatred of the liberal academic is manifesting itself in the close monitoring, controlling, public humiliation, punishment and eventually removal of erring instructors. Various testimonies from within the academia that have appeared since 2014, suggest that even the centrist perspective on any historic or social issue is unwelcome today, let alone those further away from the middle.

Double the Trouble

What also concerns some academics at this juncture is that many of those punishing, even publicly denouncing dissenting members, come from within the teaching fraternity. In January 2015, Professor Sandeep Pandey was ousted from the Benares Hindu University, without warning and with no academic or behavioral reason cited. This, after what appeared to be a sustained campaign against him – Pandey felt this was driven by the vice chancellor’s and other administrators’ strong dislike for him. Pandey told Scroll.in that this dislike appears to have been based on his aiding certain student politicians, and his social appearances (with some former Maowadis 13 years ago, and on a citizens’ defense committee for Geelani). Pandey felt he was simply muscled out in order to create an ideological vacuum for favored student leaders to fill.

For others the threat is always looming, ubiquitous. At a press conference called by Delhi’s academia on March 3, 2016, Apoorvanand, Professor of Hindi at the Delhi University, shared that these days he feels worried every time he enters a classroom. “You never know who might be watching you, ready to report what you say to the authorities”. In late February, print and new media outlets published a column Apoorvanand wrote titled “Umar Khalid, My Son”. In Lucknow University, sociologist Rajesh Mishra shared the article on his Facebook page. The very next day, Akhil Bharatiya Vidhyarthi Parishad (ABVP) members staged protests, burnt Mishra’s effigy and demanded action against him; LU’s Vice Chancellor asked him for an explanation.

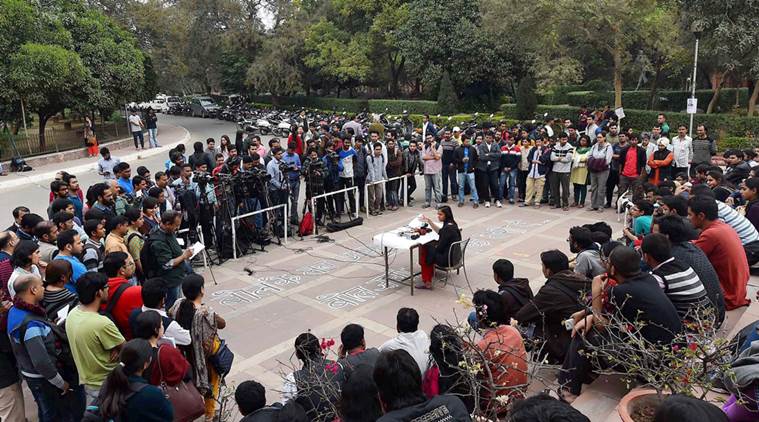

Apoorvanand’s feelings are echoed by others at the presser as well. With their pleas for academic freedom of speech and thought, the academics present confirmed an increased sense of insecurity among that community. A representation including the likes of Apoorvanand, Satish Deshpande of the Delhi School of Sociology, and Mukul Kesavan from Jamia Milia Islamia’s History department among many others, they spoke of fears not only for the physical safety of their students, but for also for the longstanding implications of such events as the JNU crackdown. Their concern is for the future of the ‘publicly funded university’ as a crucial and protected ‘space’, where young adults (and old) can learn to think critically or pursue rational, verbal debate, without fear of recrimination.

Indeed, the exercise of critical thinking seems to have long fallen by the wayside for some, as Professor Vikram Soni recently found out. Soni, Emeritus Fellow of the Centre for Theoretical Physics in Delhi, spoke of how a few days prior, as he took a stroll, was “suddenly cornered” by a random group of men, verbally abused and physically threatened, because they knew he was a professor. “I managed to talk them down, and somehow sustained a conversation with them for half an hour…I don’t know how I got out of that situation.”

Anti-Nationals Beyond Indian Borders

This sense of nervous uncertainty isn’t restricted to academics in India. Only a few hours before the Universities teachers’ presser, Dipesh Chakrabarty, an Indian historian based at the University of Chicago, talked to me about an “India [that was comparatively] much more tolerant of…academic and even political critique in the ‘60s and ‘70s.” Chakrabarty isn’t usually known to comment publicly on controversies. Sitting in Chicago and disturbed by the news filtering out of JNU, he signed a petition supporting Kanhaiya Kumar’s release. A few days later, a group called ‘Friends of the BJP’ sent him a “mildly threatening email…. [asking] if I understood the implications of supporting seditious… anti-nationals…” The current definitions of what constitutes ‘anti-national’ and ‘sedition’, according to Chakrabarty, are verging on the “absurd”.

Sanskritist, philologist, and Chakrabarty’s personal friend, Sheldon Pollock was recently made the target of a signature campaign, demanding he be removed from the position of General Editor of the Murty Classical Library of India series. He was targeted for expressing academic views on the Hindu knowledge systems that shape our society, that are in part critical, and perhaps pessimistic. Pollock has long held these views, but the timing of the petition was pegged to Pollock’s own stand on the Indian government’s handling of the JNU issue. In Pollock’s case, the petitioners chose to conflate ‘non-Indian’ with ‘anti-Indian’, in making their case for his removal. Fortunately for Pollock, Rohan Murty, who is funding the project, refused immediately to entertain any such petition. At the March 3 presser, Mukul Kesavan reminded the press, “They quietly edited the petition when it was pointed out… that they had completely misinterpreted Pollock.”

In most cases, evidence does suggest that rational argumentation on matters of nationalism and sedition are one-sided, and very often so. According to Apoorvanand, a member of a brahminical forum working to promote the Vedas called him up in November to enlist his help for a ‘Run for the Vedas’ campaign. “He said to me: ‘Romila Thapar and other conspirators are blocking the authentic knowledge of the Vedas from being known. We need to refute conspirators like her publicly…so we are going to organize a ‘Run for the Vedas’ event.

‘Sure,’ I replied, ‘but what evidence are you working with? Thapar doesn’t hold a position of authority, she just writes books. She can’t really block any knowledge flow. Have you any scholarship, any books on this? Because that’s the way to counter. A ‘run’ won’t help.’

‘No,’ came the answer.” Apoorvanand didn’t hear from the forum again.

Romila Thapar and Harbans Mukhia Speak on the Emergence of Nationalism in Indian History

Prabhat Patnaik on What it Means to be National in India