The acclaimed translator and anthologist Lakshmi Holmström died on May 6, 2016 in Norwich, UK. Shashi Deshpande and Githa Hariharan pay tribute to Holmström’s work and the friendship among them.

Image courtesy The Hindu

It was late night when the telephone rang. The caller was Lakshmi Holmström, and she immediately said, without any introduction, “I just finished your book and it’s bloody good.” I was in London for the launch of my novel That Long Silence, staying in the home of one of the Virago editors. I’d been given an introduction to Lakshmi by our mutual friend Gita Krishnankutty and I had expected that we would meet in London one of the days, have lunch together. Instead there was this generous, overwhelming response to the book which meant so much to me at that time and still does. Lakshmi did more. Reading a review of the book in one of the English papers, she wrote to Virago telling them that she found the review condescending. They invited her to London, and were obviously so impressed by her and her views that they commissioned her to edit an anthology of Indian women’s short stories. She wrote to me of this with great excitement and pleasure, and soon after she came to India to meet authors, and discover stories.

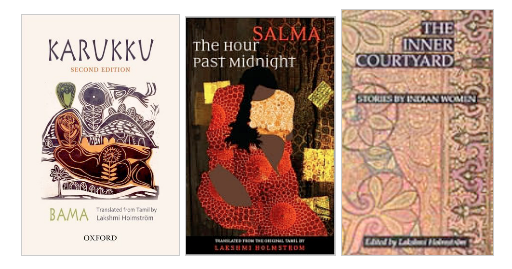

What came out of this was The Inner Courtyard, an anthology which I think is a classic. It was not, perhaps, the first anthology of Indian women writers, but it certainly was the first which gave an exciting picture of women’s writing in all the Indian languages (including English), and which was edited with meticulous care and utter professionalism. While many of the writers whose stories she chose were well known, such as Anita Desai, Ismat Chugtai, Qurratulain Hyder and Kamala Das, the anthology also included writers who would soon be just as known – Vaidehi, Anjana Appachana, Shama Futehally, Ambai and others. She had, in the course of her visit to India, managed to put together a very eclectic and unusual collection. Her introduction added hugely to the value of the book. My story, “My Beloved Charioteer”, travelled far and wide after inclusion in this anthology.

This was the beginning of Lakshmi’s career as a translator. She had translated a story of Ambai’s in The Inner Courtyard, (“The Yellow Fish”) and went on to translate some more, bringing out a collection of Ambai’s stories, A Purple Sea, which, as far as I know, was a huge success. For those of us who had only read badly and clumsily translated works from the Indian languages until then, Lakshmi’s translations were a joy to read. She didn’t baulk at doing difficult things; she translated, for instance, Bama. Only those who have translated the language of a rural community into English will understand the challenge that this is. Since then she has translated so many of the great writers of Tamil, (Asokamitran, Mauni, Pudumaipithan, Salma and so on) it is as if she was out to give the world a glimpse of the greatness of Tamil writing. She and her friend Gita Krishnankutty, who has done for Malayalam what Lakshmi has done for Tamil, have quietly gifted the world with their own literatures through translations.

Beginning with her early work on Kannagi, Lakshmi travelled a long way, both physically and as a translator, bringing professionalism and excellence into her translations. Her language, crisp and precise, was always a pleasure to read. Her handwriting was a work of art. I still have many of her letters and treasure them both for the matter and the elegant handwriting. When a person is in our midst we scarcely realise her value. Only now we see the vast amount of work she did. Living in Norwich, Lakshmi did India and Tamil writing proud. Our hearts go out to her husband Mark and her daughters. It will be hard for them, but for us her work remains.

Shashi Deshpande

The world would have to stop talking if we didn’t have translators. And this is self-evident where we live, in the midst of the unique Indian Experiment. Among our most precious “natural resources” we can count the many languages and dialects we have – whether they are flourishing, dying or dead.

I say all this to put into context my tribute to a fine translator, a passionate reader, and a loving friend.

I first met Lakshmi Holmström through the now extinct blue aerogrammes. I was in my twenties, an assistant editor at a Chennai publishing house that had commissioned Lakshmi to write a book on Kannagi. It was a “supplementary reader” for children, I think. What I remember with clarity is that this was my introduction to the Tamil Silappadikaram, an epic that is not about gods and goddesses, but about how real people can live. The aerogrammes flew between Chennai and Norwich, Lakshmi’s always written in elegant sentences and with a calligrapher’s pen. By the time we met face to face, I had a permanent relationship with the Silappadikaram, and Lakshmi and I were already friends.

Lakshmi’s work grew steadily, and she shared her discoveries with us. There was the excellent anthology, The Inner Courtyard. Then translations of Ambai, Na Muthuswamy, Asokamitran and many many more. My own memorable discoveries through her translations included Salma (The Hour Past Midnight) and Bama (Karukku, Sangati). I will never forget Lakshmi’s excitement when she told me that she was reading Bama’s autobiography, Karukku, and working on a translation.

Her translations – whether they were of novels, stories or poems — were never literal, but never too “transcreated”. The English never sounded quaint or stilted, so the reader did not feel she was in a museum, reading something “ethnic”, but a real and worthwhile text that had come to her in English as a gift. A great deal of work went into Lakshmi’s translations. But reading the fluent text that emerged, it all seemed effortless.

Lakshmi developed her own theory and craft of translation over the years, and shared her ideas with others. In one interview, she said,

Like most of us in India, I have always been fascinated by what is said in one language, and how that may be ‘carried over’ into another; what works and what doesn’t and why. …one language doesn’t ‘move into’ another automatically. Nor do they realise that when you translate a work, whether it is a poem or a long work of fiction, you have to keep in mind the integrity of the whole thing. Words and sentences may be the bricks and mortar but it has a structure as a whole that you are constantly aspiring towards. …The most difficult part of translation is, I believe, finding the ‘right’ pitch and voice of the original, and to try and match that.

Lakshmi Holmström found the right pitch as reader, translator and anthologist; and she found the perfect pitch as a friend.

Githa Hariharan