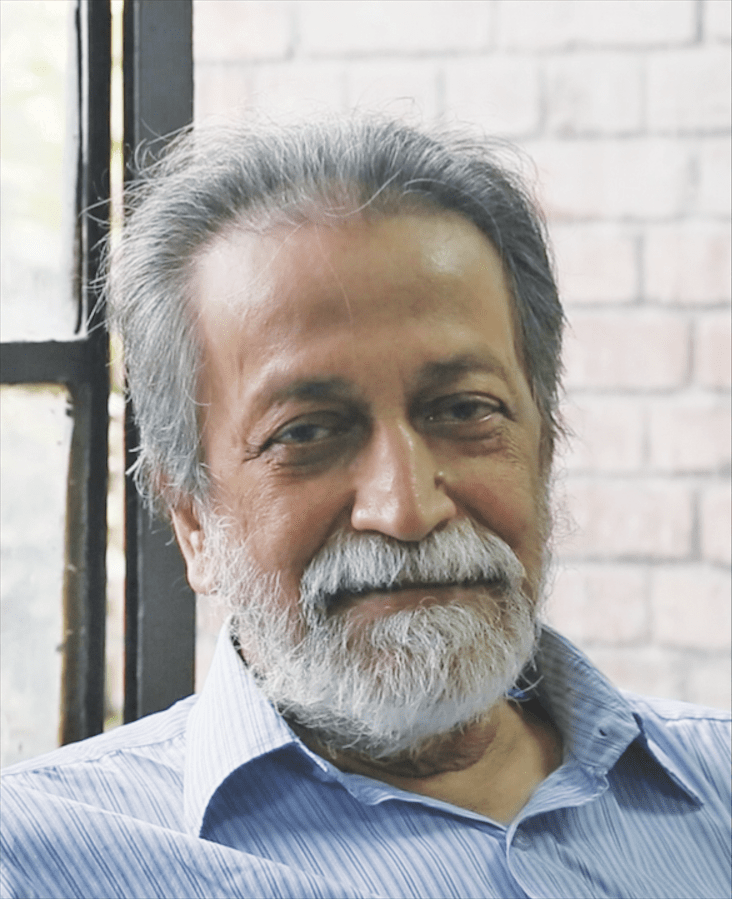

“Prabhat Patnaik, whose life and work this volume celebrates, is exceptional in many ways. While he is widely recognized as a brilliant economist with mastery over contending theoretical traditions in the subject, he made quite clear his predilection for and commitment to applying, developing and extending the Marxist approach. Known primarily as an economist of the finest calibre, he has also forayed with much effect into a range of allied disciplines in search of an understanding of contemporary reality. He is a much-celebrated teacher and academic whose contributions to scholarly debate have been profound and outstanding – but he also man- ages to be among the most active of public intellectuals: writing prolifically, travelling and speaking at all manner of venues with unmatched energy and commitment. He stands firm on issues that matter, never hedging or prevaricating; but in personal relations he is unfailingly polite, gracious and generous. His seriousness of purpose is combined with a gentle humanity and appreciation of humour, bringing out the essence of what it means to be truly civilized.”

– C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh, Introduction to Interpreting the World to Change It

This collection of essays, published by Tulika Books, brings together contributions from some who have benefited from interaction with Professor Prabhat Patnaik over decades. Interpreting to the World to Change It is a tribute to Prof. Patnaik and also a continuing conversation. Following is an extract from Ashok Mitra’s essay On Prabhat Patnaik featuring in this book.

“A physical wreck, as I approach the nineties, the thought that overwhelms me concerns the worthlessness of the life I have lived. Suddenly, a cheer lights up the mind. I have actually been the luckiest among the luckiest: Prabhat Patnaik has been, and continues to be, my dearest brother, political comrade and teacher.

He has been teaching me all the while. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the enigma of seeming ideological indifference of a China likely soon to emerge as the world’s leading power under the stewardship of an ever-vigilant communist party have little relevance; Prabhat has taught me the rigorous precision of the Marxian prognosis concerning capitalist growth and its inevitable withering away. The obsession of capitalists to maximize profit-making will ensure the steady decline of the rate of profits until it reaches zero, and this would happen irrespective of the scale and state of mobilization of the organized working class. Prabhat also convinced me of the non-contradiction between the tenets of the Marxist testament and Mao’s independent formulation in regard to the strategy of rural mobilization of the deprived, exploited peasantry. This in fact can be beautifully integrated with the grand Marxian formulation of social dynamics: the lucidity with which Prabhat, one evening, explained the relationship between the thoughts of Marx and Mao enthralled me. Predictions emerging from analytical premises can well end up in failure or disappoint for a number of reasons; the failure of a particular experiment cannot, and must not, be attributed to flaws or shortcomings in Marx’s magnificent dynamics.

It is in this context that another arena of Prabhat’s mind-boggling intellectual universe is revealed. He is not prepared to waver an inch from his conviction that Marx is the torchbearer of the classical political economy, the goal of which was spelt out by Adam Smith and elaborated by Ricardo, who actually held a grim, pessimistic view of the future of capitalism. At the same time Prabhat continues to be the most liberal amongst liberals and is open-minded enough to acknowledge the discovery of wisdom in supposedly alien territory. On completion of his academic stint at Oxford, Prabhat moved to Cambridge with a teaching assignment. It was still the era of Keynes, whose thoughts and ideas reigned supreme. Prabhat was impressed enough but not overwhelmed; the firm base of his Marxist ideology could help him to appreciate that Keynesianism was capitalism’s last-ditch battle – the public domain cannot be brushed aside in any scheme to save the existing order from the morass into which it was already falling or is about to fall. Keynes, the Bloomsbury sophisticate, was derisive about ‘the vile way of writing’ of Marxists. Nonetheless, the concept of two ‘departments’ when characterizing the productive process, he obliquely admitted, had originated with the Marxists…

I would however still maintain that all this is merely divertissement for Prabhat. He has not for one moment forgotten the central fact that economics is political economy and its quasitum is, and remains, determining the distribution of the national dividend among the classes constituting society; you may call it by whatever other fancy name, but economics continues to be distilled politics. Ever since the publication of his seminal paper in the Economic Journal on an issue concerning the roots of retarded growth, Prabhat has had no other abiding goal in his academic existence. A considerable number of famous savants, who have contributed in major ways towards the extension and deepening of the mysteries of the universe, or the process and problems of societal behaviour in the spheres of arts, science and technology, are brilliant in the repose of their study or workroom or laboratory, but are pitiably poor communicators. They fumble all the while with words, are unsure of the drawing or mathematics they love scribbled on the blackboard, and are not infrequently on the verge of breakdown while trying to put across ideas they have themselves originated to the eagerly waiting audience. Prabhat is quite the contrary. Every lecture he delivers – whether before a young crop of graduates or undergraduates, or to his academic colleagues at home or overseas, or to a crowd of innocent underprivileged peasantry or members of the working class, all cruel victims of neo-liberal economic tyranny – is sculpted poetry. His talks clarify your understanding even as you keep wondering over his uncanny ability to adjust the process of connecting to the level appropriate to the seekers of knowledge or assurance. This is where Prabhat stands far apart from the tribe to which he is by convention attributed to belong. With his magnetic attraction as an outstanding teacher, his personal charm and his organizational acumen, he has proved to be a great academic builder; the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi is now one of the most prestigious sanctuaries where scholars assemble from all over the world. Quite apart from that, though, the Centre is actually a pivotal arena for social activism. The faculty members not only teach and research, they are in the forefront in organizing and leading movements to protest against any instance of inequity, whether within the precincts of the campus or in this conflict-ridden country of ours or the big, wide world. Prabhat is their helmsman, firm but pleasant, hard in bargaining but invariably soft-spoken and polite. I can take a wager that while he has many ideological adversaries, there is hardly anybody who will consider

him to be an enemy.

That provides the clue to what Prabhat considers to be his major obligation to the nation and humanity at large. This is much more than the fact that as a front-rank economist his latest creative work immediately becomes the cynosure of excited discussion in countries across the five continents. To Prabhat, much more relevant is his identity as a political activist. He is proud of being a card-carrying member of the country’s leading Left formation. All his ‘reserve time’ is dedicated to the cause of his party, which involves constant writing, in the simplest possible lingo, in party periodicals; constant travelling across the country over the weekends, and sometimes in the course of working days as well, meeting, advising and talking to teachers, students, men and women thrown out of employment, flocks of famished landless farm workers, often a hostile crowd of disbelievers. Prabhat is available to each of them, patiently listening, taking notes, providing courage and assurance, sometimes playing a key role in resolving issues – then rushing back to New Delhi on schedule for classroom assignments or research guidance. This duality is his true identity, making him a ‘compleat man’: at least so is his credo and belief. Who will dare to debate the issue with him? His sovereignty is his prerogative, and society, even as it is today, has to grant him that.

Finally, though, a confession on my part. I have wasted a few hundred words or so about Prabhat Patnaik, but have kept from referring to what has made him what he is. Put aside all his other traits and attributes, he is a wonderful human being, extraordinarily kind to others, extraordinarily concerned with the problems of others, full of concern for others, loyal to his friends as far as loyalty could stretch, yet squeezing the time to fulfil the domestic obligations that are complex and many. When you meet Prabhat Patnaik, you of course meet a towering economist, but at the same time you have the privilege of meeting someone whose selfless-ness and determination to do good and instinctive urge to put at the very top of priorities service to others, particularly to the downtrodden, are qualities that are to be found only rarely, if at all, in others.

Allow me to present here a daring afterthought. Prabhat has become what he is, I am convinced, because he had the strange and almost unique opportunity to be reared in his early childhood in a Communist Party commune. Both his parents were dedicated communists who were closely associated with the beginnings of the party in Orissa. In those embryonic days, being a member of the Communist Party was akin to being the embodiment of honesty, integrity, consideration for others, and the deepest attachment to the credo that the sole mission in life is to give and never to ask for anything in return for oneself. Brought up in this milieu, Prabhat knows how to serve the cause of others, never for a moment taking into account the complications that could involve awkward difficulties faced at the personal level.

I am approaching the end of an insignificant life. I am happy and proud, though, that I had the privilege of knowing, loving and learning from Prabhat Patnaik.”

To get a copy of the book online, click here.