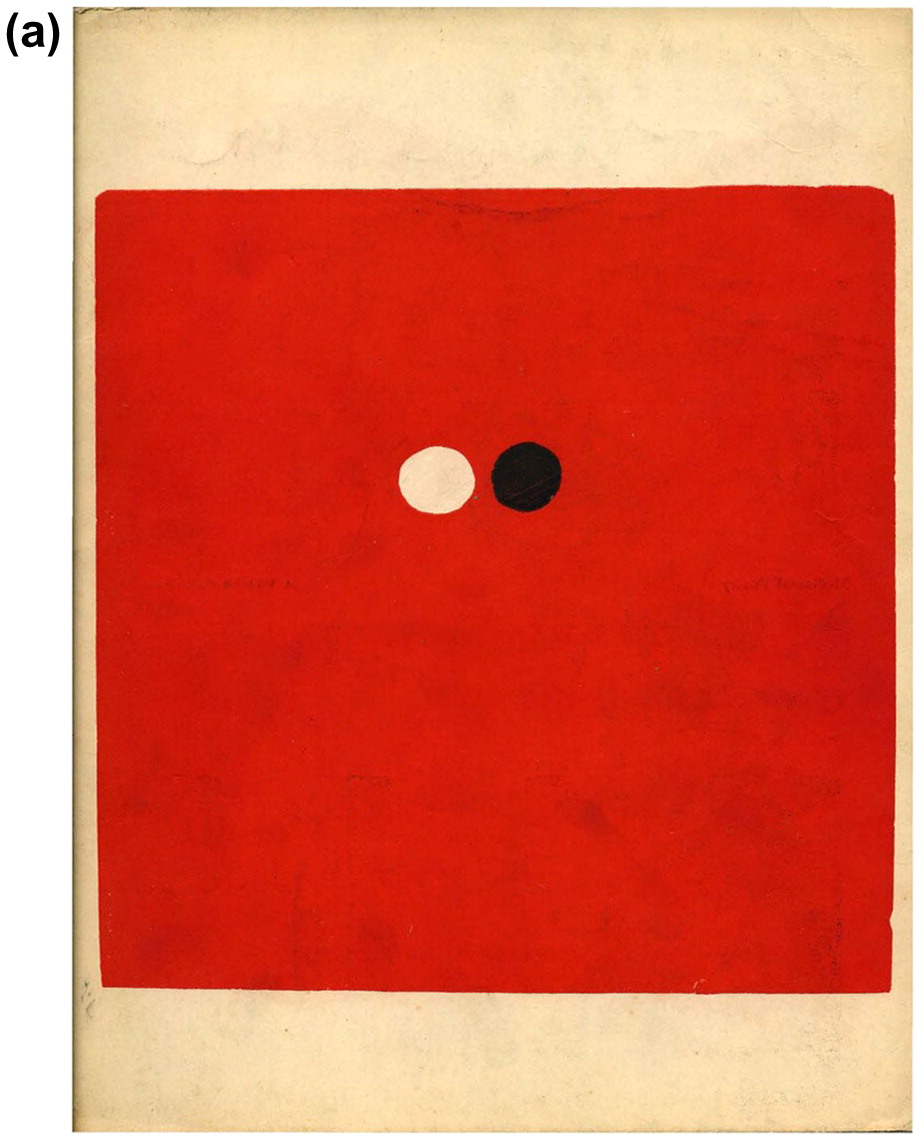

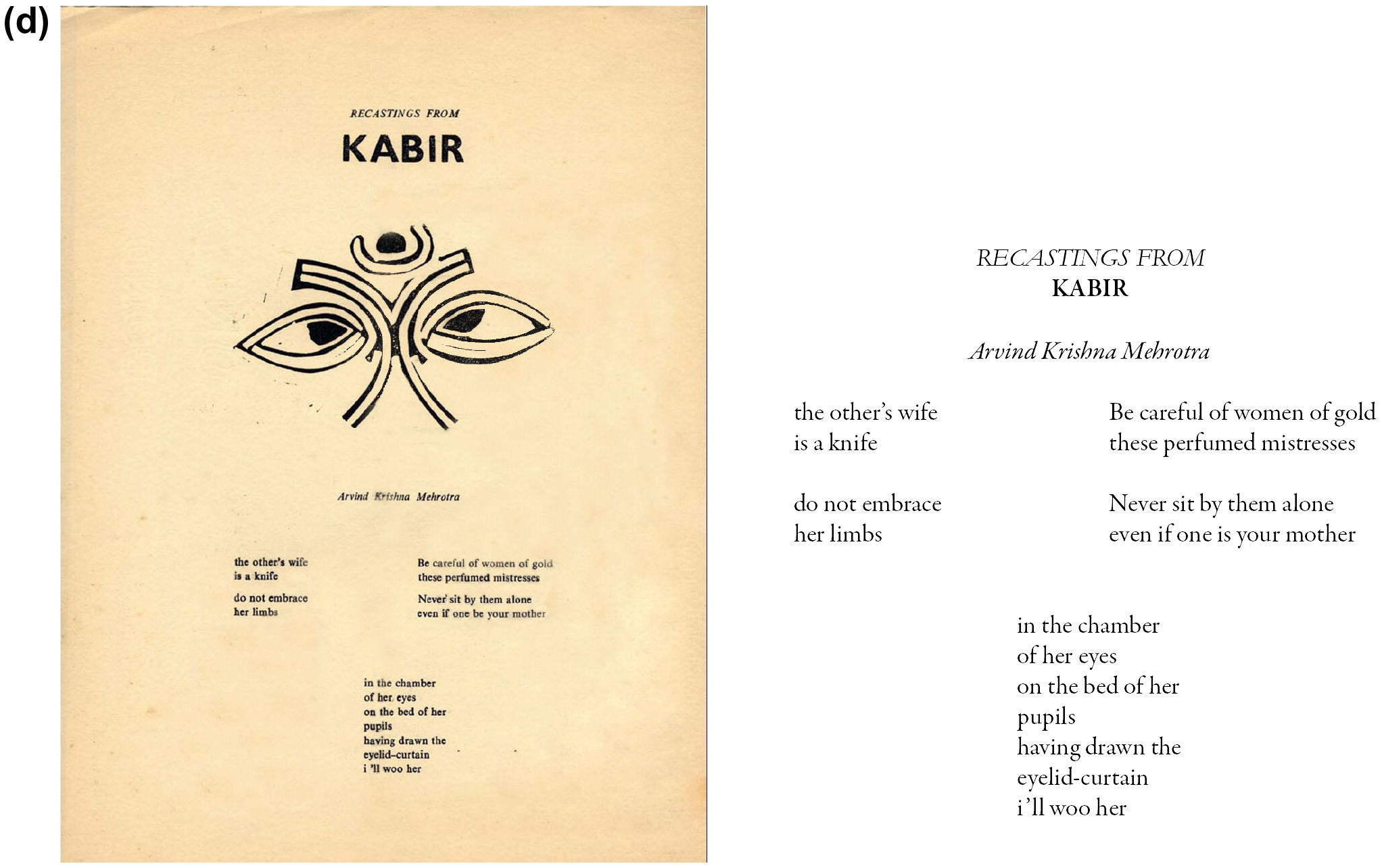

A vital presence in the artistic and cultural landscape, which he helped to define and renew in the 1960s and 1970s, Gulammohammed Sheikh has been closely associated with the “little magazine movement” in English and in Gujarati. Although he is intimately connected to the city of Baroda and to the Faculty of Fine Arts where he taught for more than 30 years, Bombay has been as much a part of his world as Baroda. And although he is widely acclaimed as one of the most important modern Indian painters, poetry has nurtured his practice as a painter. These transactions between Baroda and Bombay, and between poetry and painting, are emblematic of the influential little magazine Vrishchik, which he founded in 1969 in Baroda with another prominent visual artist, Bhupen Khakhar (1934–2003), and where he published many of the “Bombay poets”, such as Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Gieve Patel, Arun Kolatkar, Adil Jussawalla and Eunice de Souza. In a remarkable text titled “Among Several Cultures and Times”, Gulammohammed Sheikh (1989) talks about the number of traditions, spaces and temporalities that have made him who he is, and reflects on the multiplicity of artistic models that fed his mind, from Italian painters of the Early Renaissance and the Sienese School to Picasso and Michelangelo, Soulages, Rothko and Klein, but also traditional Indian glass painting, Mughal miniatures, Shekhawati murals and lurid cinema hoardings:

The multiplicity and simultaneity of these worlds filled me with a sense of being part of them all. Attempts to define the experience in singular terms have left me uneasy and restless; absence of rejected worlds has haunted me throughout. [ … ] It was a multiverse of sorts. And I decided to use it all. I felt it would be impoverishing, unreal and artificial to give up anything. (108, 116)

The interview below maps the boldness and openness of a generation of artists who felt they could “use it all”, and the extraordinary multiplicity of the “worlds of Bombay poetry”, the routes of which extend to Gujarati language and literature, to Octavio Paz and to Allen Ginsberg, to Beat poetry, Hindi cinema and bhakti songs – and also reflect the constant overlap between poetry and painting, words and images, worship and dissent. The following conversation took place on August 13 and November 3, 2015. It was continued over email.

Laetitia Zecchini: Let us start with your connection to Bombay. You held your first solo exhibition in the city and have been closely associated with many Bombay artists and writers. Yet your life and your work are intertwined with the city of Baroda. So how was Bombay, either as a lived space or as an imaginary one, influential? Did you feel that Bombay and Baroda were part of the same creative space in the 1950s and 1960s, or did they represent two different “scenes”?

Gulammohammed Sheikh: You see, before the formation of the state of Gujarat in 1960, we were part of the same state, the Bombay State. For us Bombay was not “else-where”: it was part of our own life and world. If we were to think of places within the state, we thought of Bombay as one of them. Bombay’s film industry also cast a great spell on all of us who were growing up in small towns. Many of us wanted to run away one day to the city of Bombay, and either find our bearings in the film world, or lose them!

But the primary reason why Bombay was so important is related to the domain of the arts. We were in awe of the previous generation of artists. Many of them worked in a place called Bhulabhai Memorial Institute on Warden Road.1 In the 1950s when I was growing up as a student in Baroda, I used to visit Bombay quite often, and especially the institute because that’s where M F Husain, V S Gaitonde and other artists worked. One of the Baroda artists, Prafull Dave, and another from Ahmedabad, Dashrath Patel, also had their studios there.

There were very few private galleries in India at the time. But there was, and still is, a public art gallery known as the Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay, which you could hire for an exhibition, and it attracted us all. Every young aspiring artist desired to have an exhibition in there! That’s where my first solo show took place, in 1961. Bal Chhabda,2 who later became a visual artist, but was a film distributor originally, and a close friend of artists of his generation, especially M.F. Husain, opened a gallery in the Bhulabhai Memorial Institute called “Gallery 59” because it opened in 1959. Another interesting connection was Ebrahim Alkazi, the theatre man who was also well versed in art history. He had an office in the building where he used to store his collection of colour slides of world art. I remember he gave lectures on European art with a carousel projector, an object of great curiosity in those days. He was very well known among all the artists, and was especially close to Husain, who used to make sets for his theatre productions. Alkazi came to see my solo show in 1961, and he invited me to his theatre site, which happened to be on the roof of one of the buildings near the institute. To be able to meet people like Husain or Alkazi, to see the work of all these artists or to spend time at the Jehangir, those were exactly the kinds of things that attracted us to Bombay!

We used to visit the city at any available opportunity, for a conference, for an exhibition or just to see friends. You see, for us in Baroda, it was an overnight journey. One could just take an 11 p.m. train and be there at 6 a.m., spend the whole day in Bombay, then take the train back. Bombay was also a kind of imaginary, in the sense that it was a place where you could feel free, where you could have fun loafing around, meeting friends and artists, even have a beer, for instance, and you can’t do such things in Gujarat.

The second connection with Bombay has to do with Gujarati literature. There were a lot of Gujarati writers living in Bombay – that is still the case today – and a lot of Gujarati journals being published from Bombay. So there was that kind of overlap. After the death of my literary mentor, Suresh Joshi, who edited and published a number of journals and little magazines from Baroda during his lifetime, the last journal he was editing, Etad, is now run and published from Bombay. So as far as Gujarati literature is concerned, Bombay was, and to an extent still is, as much a part of my world as Baroda.

The third connection has to do with the world of Hindi cinema. When I was a student in Surendranagar where I grew up and had my school education, I studied Hindi and English besides Gujarati at school, and I also got interested in Urdu. Born into a Muslim family, I used to go to the madrasa to read the Quran in Arabic, but I did not learn to read or write Urdu. We learnt it orally from the film songs that we all knew by heart. We also discovered that there were a number of Urdu poets in the film world or the Hindi cinema in Bombay, who were also well-known figures in the world of literature, like Sahir Ludhianvi. I still remember Ludhianvi’s heart-piercing poems and songs in Guru Dutt’s (1957) film, Pyaasa. A schoolmate of mine in Surendranagar, Devendra Doshi, who was interested in Urdu liter-ature, got books on Urdu poetry in devanagari script,3 so we could reach out to Urdu poetry.

1. “Warden Road” like many other roads or monuments of Bombay/Mumbai has been officially renamed and is now called “Bhulabhai Desai Road”.

2. Bal Chhabda (1923–2013) was also the brother of Darshan Chhabda, Arun Kolatkar’s first wife.

3. The devanagari script which differs from the Urdu alphabet – itself derived from the Perso-Arabic script – is used to write Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi and Nepali languages.

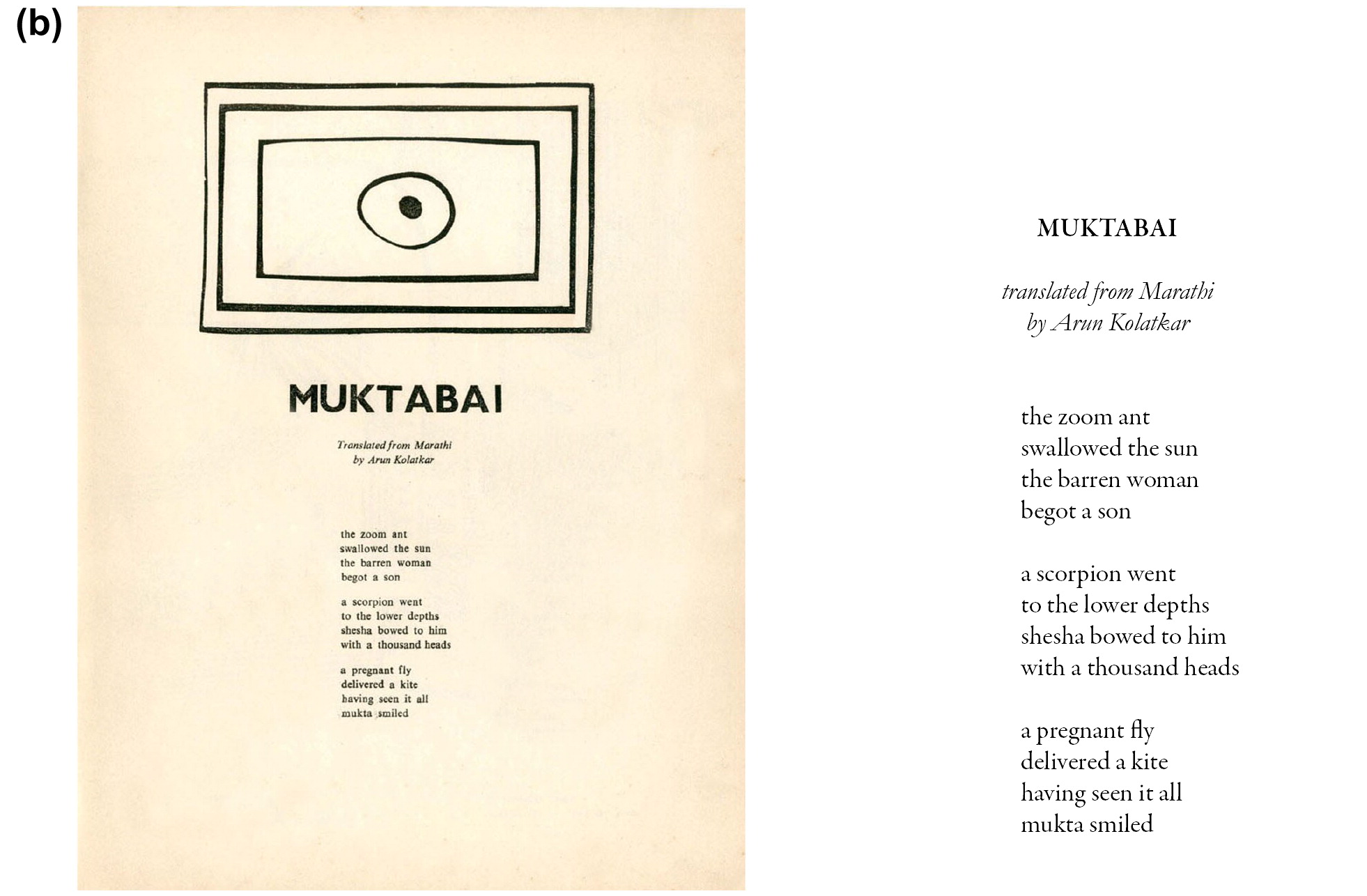

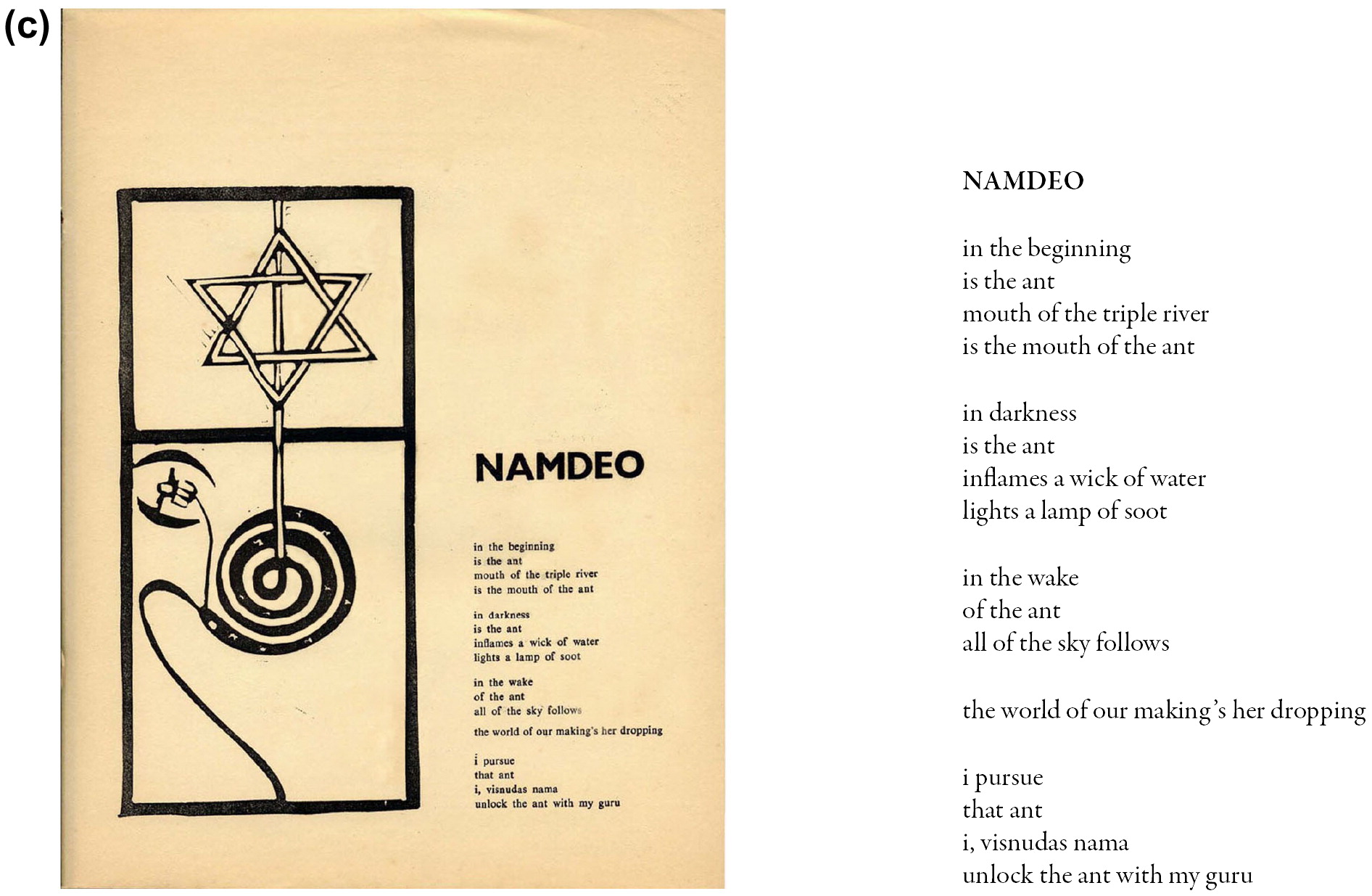

First published as “More than one world”: An interview with Gulammohammed Sheikh, in Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 53:1-2, special issue on “The Worlds of Bombay Poetry”, eds. Anjali Nerlekar and Laetitia Zecchini, pp. 69-82, 2017. This double special issue of the Journal of Postcolonial Writing, which readers in India can access online, is geared towards the larger cultural, linguistic, publishing and creative background against which we can read poets in English and in Marathi like Arun Kolatkar, Namdeo Dhasal or Nissim Ezekiel, and towards the deep symbiotic culture between poets, visual and graphic artists, publishers, filmmakers or musicians in the 50s up to the 70s. Bringing together critical or academic articles per se and personal memoirs by Arun Khopkar, Sidharth Bhatia, William Mazzarella, Vinay Dharwadker, Anupama Rao, Shanta Gokhale, Graziano Krätli, Emma Bird and Jerry Pinto, it also features new interviews with major literary and artistic practitioners of Bombay’s many worlds (Eunice de Souza, Adil Jussawalla, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Kiran Nagarkar, Ashok Shahane, Gieve Patel, Bhalchandra Nemade, Raja Dhale, Amit Chaudhuri) as well as key visual and textual documents of the time.

Laetitia Zecchini is a research fellow at the CNRS in Paris, France. Her research interests include contemporary Indian poetry and the politics of literature. She has co-translated Arun Kolatkar and Kedarnath Singh into French, is the author of Arun Kolatkar and Literary Modernism in India, Moving Lines (2014), and has just started a collaborative project on writers’ organisations and free expression.