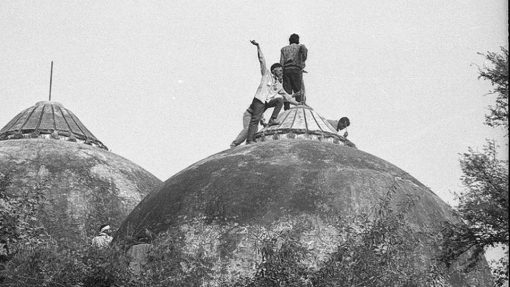

6 December 1992 proved to be a watershed moment in Indepedent India’s history as Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, was demolished by a mob of kar-sevaks following a political rally. Immediately after, the country was wracked by multiple communal riots, with over 2000 deaths reported across the country. The most terrible of these were the Mumbai riots, responsible for some 900 deaths alone.

In 2017, the Indian Journal of Secularism published Babri Masjid: 25 Years On… as a special issue to commemorate 25 years of the demolitoon. The book has multiple narratives — eye-witness accounts, essays on the political events that led upto the demolition, the riots that followed, and how different sections of society were affected by it.

The following is an interview with Sameena Dalwai and Irfan Engineer, the editors of the book. Read an extract from the book here.

Lourdes M Surpiya (LMS): Upendra Baxi, in the Foreword, mentions how this work has multiple narratives — there are eyewitness accounts, writings on the political events that led up to the demolition (such as Sudhanva Deshpande’s), and stories of its aftermath: how it affected different segments of society differently and how they dealt with it. In fact, some of the essays were originally written in other languages. Could you talk about how and why you decided to have this multiplicity, not only terms of class, but even in terms of languages? Why do you think having all these narratives is important?

Sameena Dalwai (SD): Multiplicity is the core of Indian life: languages, class, castes, genders, regions, and religions. We are not just divided between two religions but are enriched by a diverse heritage that we all carry. Yet, all of us were affected by the demolition of Babri Masjid in some way. As we realise now, those people whose life seemed untouched by the events that took place 25 years back also have to live in the era of Right wing governance now. We wanted to bring this to the fore and show that each section of society was — in some way or the other — associated with the events that led to Babri Masjid’s demolition, and in the violence that engulfed entire localities in its aftermath. This is why we have included narratives from Hindus and Muslims, from women and men, from the older generation as well as the young, and from activists, artists, common people, and journalists.

LMS: How did you go about collecting the essays for this book? And on what basis did you include the essays that you did?

SD: We wrote a concept note, which we circulated, that stated that we are looking for personal memoirs that will weave the political narrative of the nation in the wake of Babri Masjid’s demolition. People were urged to travel back in time, go back 25 years and retrieve their memories of that time. Since the book was not meant to be a political commentary, the concept note was circulated not just in the academic circles, but also activists, artists, writers, journalists, and others.

We approached the people we knew would have stories to tell. These were all fresh essays and we knew it was going to be a difficult journey for everyone involved, having to revisit and write about the events of that time. In fact, some of the people we approached declined; the memories were too painful.

We were reluctant about rejecting any stories; instead, we would first try to edit it and draw the story out. In the end, we chose the essays stories, we felt, left us with something that we could learn from.

LMS: In the Preface, you talk about how the Hindu supremacist forces responsible for the demolition are now in power at the Centre; the nature of violence that they employ isn’t the same anymore. You write, “We are therefore bringing out this special issue reflecting on those moments. The youth of the country have limited knowledge about the event.” Could you talk more about this and elaborate further on why this book, and revisiting what happened in 1992 and the events that led to it, have become absolutely imperative for us now?

Irfan Engineer: The demolition of Babri Masjid happened 25 years ago. Those who are 25 years old, or even 35 years old, have no personal memories of the event and the riots that broke out in several cities following the demolition. They did not personally witness the human tragedies. Their perception of the event is based on what they find out: through media, which has its own biases; through their textbooks and education, which too has its biases; through their community and family, whose views have also been shaped by the media.

This book has 15 essays by journalists, artists, and activists who personally witnessed the situation around them after the demolition of Babri Masjid and tried to do something about it in their own way. These personal accounts and memories of the event give a glimpse of the situation as it was then. The communal discourse and the stigmatisation of minorities that preceded and followed the demolition were nails in the coffin of democracy.

The fact that, even after 25 years, no one has been held accountable for the demolition proves the inefficiency of our criminal justice system; how it has proved ineffective when faced with majoritarian populist politics. This is what encouraged the even more heinous riots, nay pogrom, in Gujarat in 2002. The youth of the country need to know that there is no democracy without a robust regime of human rights and an effective and impartial criminal justice system.