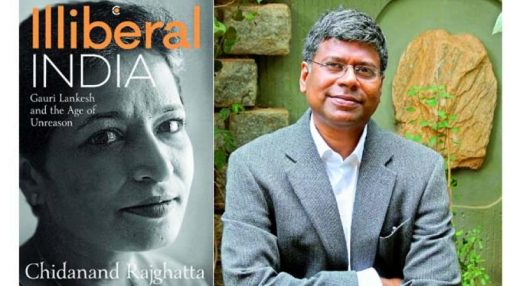

This is an excerpt from Chidanand Rajghatta’s book Illiberal India: Gauri Lankesh and the Age of Unreason, published by Context Westland. The chapter we have excerpted from “Death of a Naxalite” debunks the claim that Gauri Lankesh was killed by the Naxalites. To read more about the progress in the Gauri Lankesh murder case, read here.

Image courtesy Deccan Chronicle

Image courtesy Deccan Chronicle

Early in February 2005, Gauri called me in the US to convey the news that our college friend and classmate Saketh Rajan had been killed in a police encounter outside Kudremukh National Park in Chikkamaguluru. Saketh, who later took the nom de guerre ‘Prem’, had joined the Naxalite cause soon after our college years in the mid-1980s.

Gauri wept uncontrollably as she told me how he had been killed in cold blood by the police along with an associate named Shivalingu; they were possibly tortured before they were shot, she said. The authorities would not hand over the bodies to either family or friends. Later, they spirited them away and cremated them in a hurry to prevent the dead men from being celebrated as martyrs by their comrades. Sections of the police even defied the executive to prevent what they termed ‘untoward incidents’.1

Gauri, like the rest of us, had been out of touch with Saketh when I left for the US in 1994. They reconnected in June 2004 when she was one of the few invitees to a press conference Saketh and his fellow Naxals held in Karnataka—a state that was not known to be a Maoist haven—to highlight issues in Kudremukh that adversely affected tribals in the region. She was part of a fact-finding committee set up under the aegis of the Citizens Initiative for Peace (CIP), when Saketh came to know of their presence in the area and invited them to a forest hideout to explain their issues.

‘The press meet shattered a few myths being spread by the police,’ Gauri would write later.2 ‘For one, they were not Naxalites from Andhra Pradesh but people born and brought up in Karnataka. Secondly, that they were not some ragtag gang of misguided youth but a political party that had taken up the cause of tribals in the Kudremukh National Park. In their briefing, they said that they were ready for talks but would look forward to the government first meeting some Adivasi demands.’3

Karnataka’s chief minister at that time was a genial, rotund man named Dharam Singh, another socialist-turned-Congress party satrap who was widely seen as good-natured but ineffectual. Singh agreed with Gauri that the Naxals represented the legitimate grievances of tribals.

‘Our intention was to create a climate where the government and the Naxals could initiate talks in the larger context of people’s longstanding needs and development issues. It is important to note that the Adivasis had been fighting against their eviction in the name of a national park and for their traditional rights. But successive governments had not addressed them,’ Gauri wrote.4 ‘While we appealed to the Naxals to lay down arms, we also appealed to the government to cease combing operations as the first step towards holding talks. We were worried that the police, who had killed two women Naxals in November 2003, would end up killing more. If that happened, there would certainly be a Naxal backlash. Saket’s death triggered what we had feared for so long.’

[…]

Saketh hailed from an orthodox upper-caste family in Mysore. His father S.K. Sounderrajan was a major in the Indian Army who had taken early retirement and managed a gas station. Typical of south Indian families those days, his parents wanted him to be a doctor or an engineer. He even enrolled briefly in an engineering college in Mysore, the city itself being a haven for potential gearheads (it was also home to the company that made Jawa and Yezdi motorbikes). Mysore was also our annual haunt for college festivities around the 1980s, although neither Gauri nor I recalled meeting Saketh then.

But he soon dropped out and chose to study literature and journalism at Maharaja’s College. This is where, as an undergrad, Saketh took a stand against the Emergency. He later headed out to the Indian Institute of Mass Communication in Delhi, where he was Gauri’s senior, before he returned to Bangalore and enrolled at Bangalore University for a Master’s in Mass Communication, where he was my classmate. He wasn’t particularly interested in Marshall McLuhan, William Schramm and the others who were thrust upon us, much less Tom Wolfe and Hunter Thompson.

One of Saketh’s early influences was The Wretched of the Earth, an analysis of the dehumanising nature and effects of colonisation, by the Afro-Caribbean writer, philosopher and psychiatrist Frantz Omar Fanon. First published in 1961, Fanon’s canon inspired national liberation movements and radical political organisations in countries ranging from Sri Lanka to South Africa, Algeria to Angola. It speaks to how far ahead of the pack Saketh was at the time that he was soaking up Fanon, Sartre and other such writers when we were entertaining ourselves with P.G. Wodehouse and S.J. Perelman, not particularly worried about the human condition.

By the time he turned up in my class, Saketh had already earned some notoriety. The story went that after securing the first rank in his IIMC diploma course, he found that Vidya Charan Shukla, a former information and broadcasting minister, was to hand over the awards and certificate at the institution’s annual convocation. A fierce critic of the Emergency, of which Shukla was an unrepentant defender and one of its executors, Saketh went to the convocation, but when his name was announced to receive the award, he declined to go on stage as a mark of protest. Another version of the story is that he went on stage but walked right past Shukla’s outstretched hand in a public rebuff.

Saketh spoke little about that incident, or about when exactly he began to develop radical and militant sympathies. He was the quiet, brooding type, and it took me several months to engage him in conversation. But we surmised that his ultra-left ties began in Delhi during his IIMC days when he was said to have come in contact with the People’s War Group (PWG), an extremist outfit that claimed to represent peasants and landless communities, and adhered to the ideology of Mao Tse-Tung’s organised peasant rebellion.

[…]

We had little idea what Saketh did in the years after he evaporated from GAS College, other than what we read in the Comrade Chronicles. We do know that he was among the first to report (when he was still a journalist), and then lead a protest against, the setting up of the Rare Earth Material Plant at Ratnahalli near Mysore, which was reportedly designated for the enrichment of uranium used in nuclear weapons. It forced officials of the Indian nuclear establishment to come out and address people’s concerns on safety issues. He also played a ‘leading role in thwarting the joint venture of imperialist and comprador ruling classes of Karnataka in setting up the “Japan Industrial Township” at Sathanur near Bangalore’, his comrades recorded.

However, the activism that eventually led to Saketh’s death was said to be his opposition to mining operations in the Western Ghats by KIOCL Limited, formerly known as Kudremukh Iron Ore Company Limited. Saketh planted the seeds of Naxalite activity in areas rich in crop and ore, the well-off and rain-fed Malnad region. ‘It is not an exaggeration to say that he was the “brain and spine” of the revolutionary movement in Malnad,’ the chronicles boast in purple prose.

In Mysore itself, long before he joined the ultras, when many of his peers were writing namby-pamby features about ‘trends’, Saketh’s journalism was infused by socio-economic and environmental concerns. His Mysore associates remember his articles on preserving the Kukkarahalli lake ecosystem, the sufferings of tribals in Heggada Devana Kote taluk forests and, most of all, his stories on the so-called ‘bomb factory’ in Ratnahalli that forced officials of the Indian nuclear establishment to come out and address people’s concerns on safety issues.

By the early 1990s, Saketh had disappeared completely, not just from the public eye but also from friends’ circles. No one had seen him for months. Even a friend who dated him briefly, or at least had a crush on him in college, reported him M-I-R, Missing-in-Revolution, as opposed to others who were merely m-i-r, missing-in-romance.

Always a romantic, according to colleagues who knew him better than I did, Saketh did have his share of dalliances, eventually marrying Rajeshwari, a young journalism graduate who also joined him in the Naxal movement and went underground with him. A non-combatant who edited Vanita Vimukti, the women’s journal of the Naxalite movement, ‘Comrade Raji’ as Saketh would come to call her, was killed in a police encounter on 20 March 2001 in the forest of Kothapalli in Andhra Pradesh’s Vishakhapatnam district. According to Saketh, who wrote a moving dedication5 to her in the second volume of the History of Karnataka, which she helped him put together, Rajeshwari was captured that afternoon by a twenty-member detachment of the Special Task Force, tortured for more than four hours and finally shot in the back of her head. Her death appeared to militarise Saketh even more. ‘As the revolution rages across our land, the fascist rulers and their state will discover more and more that the memories of the dead are not as easily erased from the hearts and minds of the living. That is what history—the history of class struggle, is also about,’ he wrote in the tribute.

By the time he went underground in the early ’90s, Gauri was with Sunday in Bangalore, and I had moved back to Delhi.

[…]

Soon after her meeting with Saketh and his comrades in their forest hideout, Gauri had been drafted by the Karnataka government to help bring the Naxals of Karnataka into the mainstream. Their personal friendship also bridged the trust deficit. She also saw an element of romance about Saketh’s struggles and his hardscrabble life, telling me once it reminded her of her father’s poem rendered into a poignant song ‘Kempadavo Ella Kempadavo’ in his movie Ellindalo Bandavaru:

All of it turned Red, all Red

Plants and trees which were green,

Flowers which were all white

Turned Red like they’d drunk blood

Grass and creepers turned Red…

But the police and law enforcement folks were not impressed; they saw it as a black-and-white law and order issue. Starting in 2003, encounters between police and Naxals were frequent in the Western Ghats, resulting in the deaths of Naxals, locals and police. 6

Saketh was killed by an Anti-Naxal Task Force in what was said to be a routine encounter during a search operation that was continuing despite the government outreach for talks. The Naxals claimed 7 that the encounter took place after a ‘Bajrang Dal goon’ named Sheshaiah Gowdlu, a ‘police informer’, had ratted to the police about Saketh’s whereabouts. Other reports said Sheshaiah was a Congress activist, and the whole episode was part of a turf battle, and that far from being an informer, Sheshaiah had challenged Naxal methods and ideology in the region. 8 Saketh’s death shook Gauri, particularly the manner in which the police disposed of the body. She raised a huge stink, even calling me up to ask if I could raise the matter in human rights circles in the US.

Saketh’s death did not go unanswered. According to the Comrade Chronicles, in the biggest attack staged on Karnataka soil by the People’s Guerrilla Liberation Army of AP’s Anantapur district, some 200 Naxals, including fifty women, attacked a Karnataka State Reserve Police camp in a school at Venkatammanahalli in Pavagada taluk of Tumkur district. They killed six constables and chronicled this act online under the headline ‘Retribution’. 9

A few weeks later, on 17 May 2005, Sheshaiah was shot dead. A press release from the Communist Party of India (Maoists) claimed responsibility for the killing, saying, ‘Despite cautioning, Sheshaiah refused to mend his ways and finally there was no other way but to eliminate him.’ 10

By this time, Gauri had become a ‘Naxalite poster girl’, teased about her sympathies being with the ultras (even by friends), and more seriously and worryingly, resented by many police officials who had lost their colleagues to Naxals. As a result, when Gauri was assassinated, some cops were quick to point out the alternative theory that she had been eliminated by Naxals unhappy with her efforts to mainstream them, or of ‘mainstreaming gone wrong’, even though Naxals themselves rejected the theory. Politically too, it became expedient for right-wing extremists to point fingers at left-wing ultras. 11

In this era of fake news, extremists on the right generated plenty of tripe that sections of the public, some credulous and others forsworn to the cause of Veerashaiva–Lingayat unity in furtherance of BJP’s electoral fortunes, lapped up. Gauri’s killing, according to the right-wing grapevine, was the handiwork of rogue Naxals. Or it may have been because of family disputes. Or because of financial wrangles. Or romantic tangles. Or just a robbery gone wrong. Anything but an extremist right-wing killing.

Lost in the fake news babble was a simple fact: forensics reports showed a strong possibility that the same weapon had killed Gauri and Kalburgi. 12 Why would Naxals kill Kalburgi?

In an article Gauri wrote in Tehelka on 10 February 2005 about Saketh’s death, under the headline ‘In Death, a Star’s Dawn’, noting that she and her friends in the CIP ‘had tried to ensure a decent burial for the Naxals, (but) the Sangh Parivar started baying for our blood for “supporting Naxals”.’ And about how the police had defied the chief minister—by refusing to hand over the bodies of Saketh and his colleague—because he had said on record that he was, ‘feeling terrible that such a brilliant man had been killed’. Saketh’s death pushed Gauri even further left, and for a while I thought it had affected our friendship too.

She knew I had done some reporting on the Naxal issue in Warangal in Andhra Pradesh and in Bastar, Madhya Pradesh, but picking up an ancient .303 or even a modern AK-47 was not my idea of bringing about change. She agreed that violence was not the answer, but what is one to do when the state is indifferent, she argued. That’s the same argument terrorists make, I reminded her. Meanwhile, Gauri’s domestic crisis came to a head in 2005. After refusing to print her editorials and columns on Saketh’s death and the Naxal issue, her brother Indrajit literally forced her out, compelling her to start a separate paper. It had been coming for some time, and she probably anticipated it because she had already registered the title Gauri Lankesh Patrike so she could make a seamless transition to the new paper without missing an edition.

1. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/High-drama-as-police-perform-Naxals-last-rites/articleshow/1015533.cms.

2. Gauri Lankesh, ‘In Death, a Star’s Dawn’, Tehelka, 19 February 2007.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. https://ourrebellion.files.wordpress.com/2010/09/book-making_history_vol_21.pdf.

6. http://www.deccanherald.com/content/56040/tracing-naxal-footsteps-western-ghats.html.

7. https://sites.google.com/site/sakethrajan/.

8. http://www.thehindu.com/2005/05/20/stories/2005052010680400.htm.

9. Ibid.

10. http://www.thehindu.com/2005/05/22/stories/2005052205510300.htm.

11. https://www.thequint.com/news/webqoof/investigators-say-no-lead-suspect-in-gauri-lankesh-murder-case-yet and https://www.thequint.com/news/webqoof/investigators-say-no-lead-suspect-in-gauri-lankesh-murder-case-yet.

12. http://indianexpress.com/article/india/gun-used-to-kill-gauri-lankesh-is-the-same-one-that-killed-m-m-kalburgi-forensics-4842625/