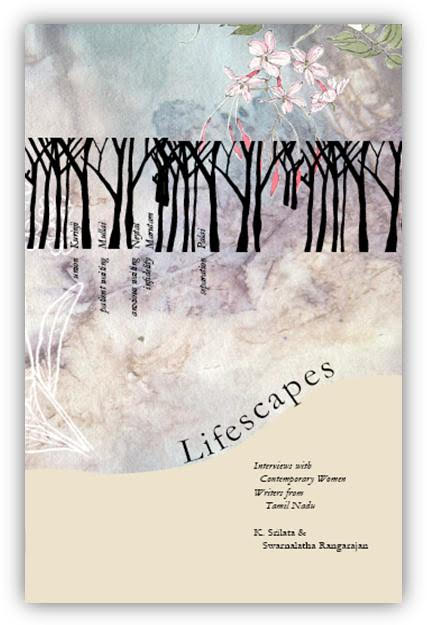

A unique anthology by K Srilata and Swarnalatha Rangarajan, Lifescapes: Interviews with Contemporary Writers from Tamil Nadu, presents the experiences and views of seventeen contemporary Tamil women writers whose works explore the implications of being female in Tamil Nadu today, in serious and playful ways. Challenging the rigid, polarising binaries of the “inner feminine”, or aham, and the “outer masculine”, or puram, prevalent in classical Sangam literature, the writers in this volume draw attention to the inseparability of issues like gender, body politics, caste hegemony, mythopoesis and environmental justice, in their writing. The following is an excerpt from an interview with poet Malathi Maithri.

You are known for the lead you have taken as a feminist poet, resisting and challenging the forces directed against women in contemporary Tamil writing…

I was naturally inclined towards working against structural forms of oppression, both gender oppression as well as oppression that is caste-and religion-based. Later, this inclination informed my politics as well, and I think it has been an important influence. I am more interested in political activities than in writing. Had the political groups here functioned well, had they recognised women’s rights and voice, I would have become a full-time party worker. At the age of nineteen, when I joined the People’s War Group1 , the communists were worried that I wore trousers and jeans. Followers of Periyar and Tamil patriots concurred with those communists. I wanted to spend my time serving people, not on correcting such regressive mindsets. As a way of identifying me, they would ask, “Do you mean the Malathi who wears pants?” trying to joke about it. There was no other Malathi in the party at that point in time, and no other woman wore jeans then, either! A woman’s body, her appearance, her functioning, as well as her ideas, were all under surveillance here. It was very oppressive. Only Marxism brings freedom to those oppressed people who demand the public ownership of property; but if revolutionary Marxists within the party were oppressing women like that, how could their policies and protests be effective?

There is, undoubtedly, a preoccupation with the politics of the body in your work. You and other women poets writing in Tamil have literally fashioned a language of subversion.Were you ever conscious of recreating a storehouse of myths and images and of its implications for other women writers in Tamil Nadu? Are you conscious of creating a new idiom?

The pure-impure binary in Indian society has a significant role to play in the oppression of women. Mythology, folk literature, oral traditions, modern literature and the visual media have all been waging a war against women on the basis of a male-female binary. Patriarchal ideas have flourished in all literatures, from ancient mythology to modern writing. I felt that we needed a literature to celebrate the female body, we needed to find a new language of poetry, a language that could bring about a recreation that would pulverise patriarchal authority and liberate the body of the woman. In my poem Slaughterhouse, I have included symbols representing women breaking out of corporate culture, a culture which employs modern methods to exploit and enslave the female body.

As a woman interested in the body and sexuality, are you conscious of having had to wrestle for a space from which to write? What has the contribution of older women writers been to the space that is now available to women? Do you see yourself as part of that community?

Women of my generation fought several battles. It has now become acceptable to write about the woman’s body; many younger women poets are able to write freely today, without restraint. Outside of writing, we have also brought about changes in the cultural sphere. We have transformed expectations around women’s bodily appearance, enabled women to remain single or to live with a male partner. All these changes have touched the lives of young women poets who are writing today. But their failure to take poetry to the next level, their failure to create diverse forms, the stagnation that has set in—all of this is worrying. Many women are gravitating towards popular media, which is one reason for this regression in women’s writings. As a woman writer, I identify closely with identity politics. I do not want to be subsumed in male narrative spaces due to my lack of identity. When a list of Tamil poets is compiled, women poets are not included in it. After much deliberation and advice, they include a few women poets who are popular. Even today, popular male writers continue to make philosophical claims that women’s writing does not qualify as writing at all.

[…]

What sort of opposition have you faced from mainstream writers? How did you respond?

When I started out as a writer and activist, my appearance and lifestyle generated heavy criticism. I received birthday wishes in the form of pornographic poems which were released in a magazine called Oodagam, run by Ravikumar2 , A. Ramaswamy3 and Arunan4. Thanks to complications arising from this kind of negative publicity, writers and party leaders from Pondicherry excluded me socially. However, I remain unfazed. When I published my first collection of poetry in 2001, some writers wrote letters filled with vitriolic hatred. These letters were addressed both to me and to my publishers. On television, as well as in magazines, lyricists and poets made controversial statements, to the effect that women poets should be doused with petrol and burned. I handled these problems by sending them legal notices. When they published abusive commentaries in magazines along with my picture, when they accused me of writing pornographic poems, I was terrified that my landlord would find out and ask me to vacate immediately. But I didn’t succumb to this kind of cultural policing. I didn’t have anything to lose in this world, but myself.

Writers and the literary world continue to treat me harshly. Recently, some people asked the printers of my Anangu Penniya Pathippagam (The Anangu Feminist Publication) to stop printing my books. This is because they see me as dangerous, as someone who challenges men, especially when they attack women.

1. People’s War Group is another name for the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist). It was an underground communist party and merged with the Maoist Communist Centre of India to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist) in 2004.

2. Ravikumar is a well-known Tamil intellectual and anti-caste activist responsible for shaping the little magazine, Nirapirakai.

3. At the time of the incident, A. Ramaswamy was a professor in Pondicherry University. He is currently on the faculty of the Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli.

4. At the time of the incident, Arunan was an official with All India Radio.

Malathi Maithri was the first woman from the fishing village of Villianur in Pondicherry to have completed her school education. Her poetry collections include Sankarabarani, Neerindri Amayadhu Ulagu (There can be no Earth without Water); Neeli, Yenathu Madhukuduvai (My Wine Glass); and Mul Kambikalal Koodu Pinnum Paravai (Birds that Weave Nests Out of Thorns). She is the founder of Anangu PenniyaIyakkam, a feminist organisation. Her works have been translated into English, Hindi, Malayalam, Kannada, Galician, French and German.

K Srilata is a poet, fiction writer, and professor of English at IIT Madras. Her collections of poems include Bookmarking the Oasis, Writing Octopus, Arriving Shortly and Seablue Child. She co-edited the anthology Rapids of a Great River: The Penguin Book of Tamil Poetry. Her novel Table for Four, published by Penguin, was longlisted in 2009 for the Man Asian literary prize.

Swarnalatha Rangarajan is Charles Wallace India Trust Visiting Fellow, Michaelmas 2013. She has been Associate Professor of English at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Madras since 2010. She is the founding editor of the Indian Journal of Ecocriticism (IJE) and has published articles on ecocriticism in several journals.