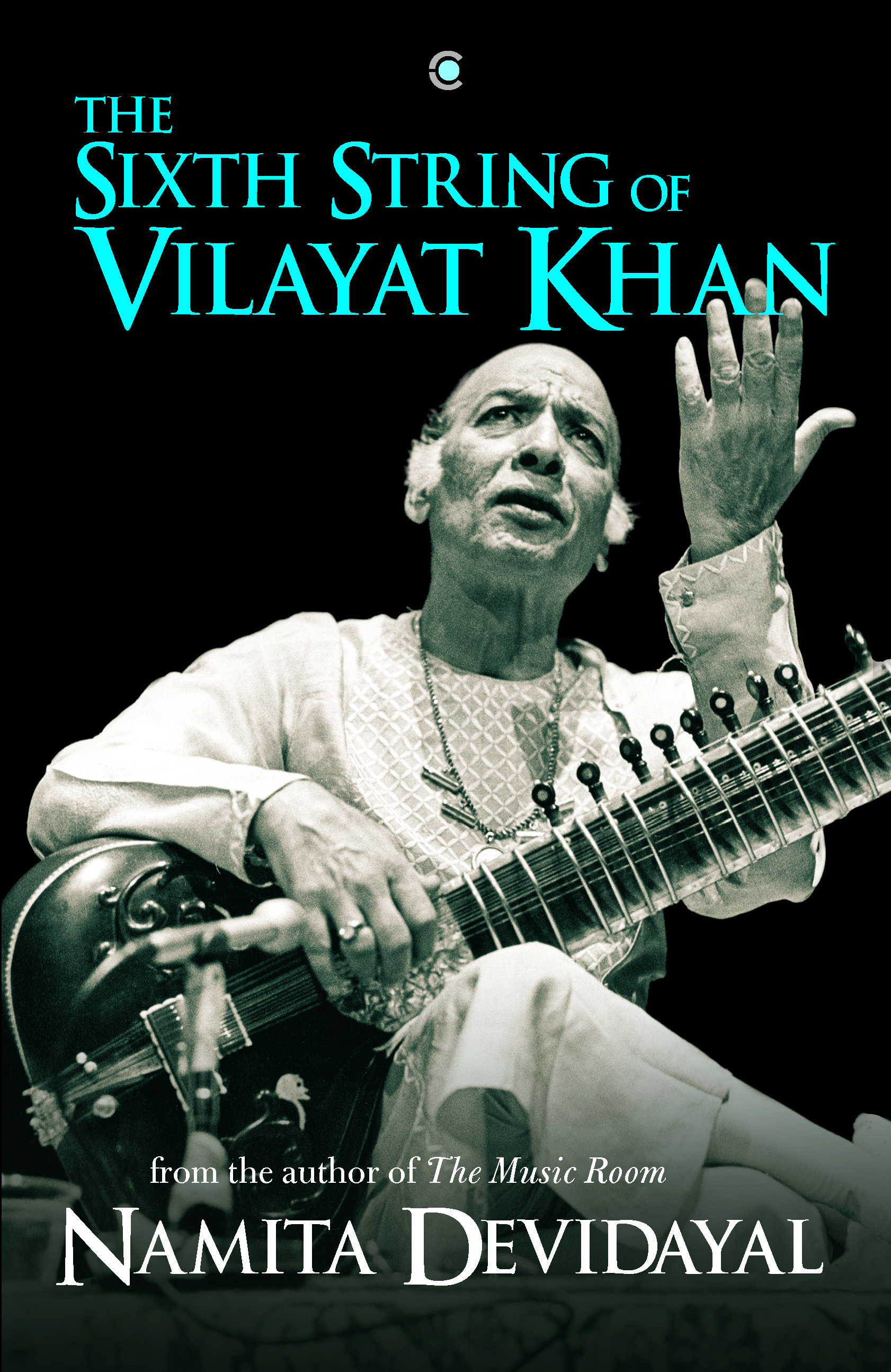

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan is a feat of research and storytelling by Namita Devidayal. The book tries to capture the extraordinary life of an artiste who fundamentally and forever changed Indian instrumental music. Filled with previously untold stories about the man and the musician, this is an intimate portrait of an uncommon genius.

The following is an extract from the chapter “Fading Out” of the book.

In 2000, the Indian government announced Ravi Shankar’s Bharat Ratna. The front page of The Times of India carried a controversial piece in which Pandit Jasraj, one of India’s most highly regarded singers, declared publicly that Vilayat Khan deserved India’s principal award over Ravi Shankar.

It’s not as if Khansahib did not care. He did. Sometimes he checked how much Ravi Shankar was getting from concert organisers and asked for just a little more. But the rivalry was dramatised by their students and the buzzing bees of the music world rather than the two artistes themselves. Both probably knew deep within that comparison and competition in music was as pointless as comparing two stars in the Milky Way.

The cultural critic Narayana Menon had once said of them: ‘To have two sitar players in our midst of the calibre of Ustad Vilayat Khan and Pandit Ravi Shankar is a measure of the vitality of the music scene. We need them both to widen our horizons and enrich our experience. Two Ravi Shankars would not have served the same purpose. Nor two Vilayat Khans. We want the individuality, the equipment, the achievement of each in his own respective field.’

The issue became a talking point in the music world but life went on, and Vilayat Khan continued to play, teach and, even at that age, be a student of music. Neither fame nor the frailty of age stopped him from wanting to learn something new to bewitch his audiences, to bring them closer to him.

When he was about seventy, Khansahib was on his annual winter excursion from Princeton to Calcutta. His loyal friend Jayanta-da arrived at the airport to receive him in his familiar old Ambassador. As they drove to his flat in Hastings, Vilayat Khan turned to his friend.

‘Jayanta babu, did you find him?’

‘I did, I did,’ Jayanta-da said, looking away and squirming at his own lie.

For about a year, Vilayat Khan had been murmuring about a folk song in raga Bhatiyali that he had heard many years ago. He remembered the tune but couldn’t recall the words. All he remembered was that there was a boat, a river and a supari tree, and that it was beautiful and mournful. Whenever he spoke to Jayanta-da on the phone from Princeton, he brought it up. Find me that song…

At first, Jayanta-da dismissed it as one of Khansahib’s whimsies. But here he was, many months later, and it was the first thing he was asking for. He couldn’t procrastinate anymore. When Vilayat Khan wanted something, he made sure he got it. He became obsessed.

In the 1950s, he had been part of an Indian government-sponsored cultural delegation to Russia. As the lights dimmed in the grand Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, and the Russian sopranos’ voices soared divinely, the young Vilayat Khan started worrying about how the Indian performers could match this beauty. That was when one of the delegates, a Bengali folk singer called Nirmalendu Chowdhury, went on stage and sang the startlingly beautiful song that Khansahib was now haunted by.

Like many magical memories that get eroded in the flow of life, the words of the song had gone. What remained was the emotion. Now, so many years later, he wanted to sing the song.

The folk singer had long since died, but his son Utpalendu Chowdhury was singing the same songs. Jayanta-da managed to get in touch with him. He called him that very day and said that Vilayat Khan wanted to meet him. The surprised singer agreed to come across.

The next day, Khansahib asked again about the boatman’s song.

‘Did you find it? When is he coming?’

‘Tomorrow morning to my house.’

‘Good.’

The folk singer arrived in the morning. Vilayat spoke to him about the cultural delegation to Moscow and the lovely time he had with his father. Then he got straight to the point. He brought up the boat and the trees and hummed the tune.

‘Can you teach it to me?’

Utpalendu looked aghast. ‘Sure,’ he mumbled.

Utpalendu got up, said he would be back, and disappeared from the room. About twenty minutes later, there was no sign of him. A baffled Jayanta-da went looking for him, wondering what could have happened. He was told by his staff that the visitor had run down the stairs, almost tripping on his dhoti, and slipped out of the main door. He later found out that Utpalendu was so daunted at the thought of teaching a song to such a great maestro that he had simply fled.

But Khansahib was not deterred. He called Utpalendu and reassured him, and this time, he went to the singer’s house. By now, the folk singer had gathered himself. Vilayat Khan sat on the floor next to him.

‘What are you doing, Khansahib? You can’t sit there. Please sit on the couch.’

‘No, I am fine here. Today, I am the student and you are the teacher.’

Utpalendu smiled. He shut his eyes and sweetly sang the song for Vilayat Khan. Khansahib smiled as well as he wrote the words on a piece of paper in Urdu.

About a month later, Vilayat Khan was performing at the Ramakrishna Mission outside Calcutta. He announced, ‘I want you to hear this folk tune which I had heard Nirmalendu Chowdhury sing many many years ago. It is an ode to all the boatmen who drift along the rivers of Bengal …’

He sang it beautifully, and the audience found themselves immersed in all the beauty and sadness of their land.

Deepak Raja once wrote of Vilayat Khan: ‘He valued the approval of discerning and cultivated audiences, and eschewed populism of every variety. But his was not a snobbish elitism that makes music inaccessible to the majority. His repertoire was dominated by popular ragas and talas and always had a reasonable component of semi-classical music.’

The thing about Vilayat Khan is that he may have been an ustad, good and proper, but he never stopped being a student. His battery never died—neither did his sense of humour.

Sometime after this, Vilayat was checking in at the British Airways first-class counter at JFK Airport in New York. He was on his way to a concert in Europe. His son Hidayat was accompanying him. The big brown Paxman leather sitar case was taken off the trolley and placed in front of the attendant.

‘Sir, what does this contain?’

‘It’s a sitar,’ Khansahib grunted with some irritation. ‘An Indian instrument.’

‘A seetaaaar!’ The British Airways man at the counter suddenly became animated. ‘I know Raaaavi Shankar. I love Raaaaavi Shankar. I love what he did with the Beatles. Do you know Raaaaavi Shankar?’

Vilayat Khan scowled at him. He’d been through this ridiculous routine so often and yet it irked him every single time, always triggering a mildly nauseous sensation.

Then, suddenly, he grinned widely and said, ‘Of course I know him. Didn’t you hear, he died this morning? It’s so terribly sad. You’ll hear it on the news, I’m sure.’

Hidayat almost choked on his blueberry muffin. He twisted his lips in an effort not to laugh, then spun around so that he could hide his face. He didn’t know whether to be shocked or amused or embarassed by his father’s unorthodox behaviour. Then it hit him, again. This was Vilayat Khan. Enough said.

Read more:

Malathi Maithri: “To control my language would be the equivalent of killing myself”

“The song is the emotional expression of the character”

Art Attacks: The Conflict between Community and Individual Rights