Mika Natif at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU

Mika Natif at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU

Traditional scholarship has viewed South Asian art under the shadow of a European “influence”. In sharp contrast, art historian Mika Latif’s imaginative work on Mughal courts, Akbari paintings and eroticism in the arts of the Islamic world, offers new ways to read artistic dialogues across cultures. Her recent monograph, Mughal Occidentalism (2018), published by Brill, is a detailed study of Mughal paintings, which challenges the conventional classification of material culture on regional, communal, dynastic, or temporal identities.

In an interview with Somok Roy, Mika Natif reflects on the world of Mughals, teaching humanities, and ‘recasting’ women in the histories of early modernity.

Mughal Occidentalism (2018), published by Brill, focuses on Mughal-Renaissance cultural exchanges

Mughal Occidentalism (2018), published by Brill, focuses on Mughal-Renaissance cultural exchanges

Somok Roy: In Mughal Occidentalism (Brill, 2018), you locate the relationship between Mughal art and European art, in trans culturalism, which is different from the traditional idea of a dominant European “influence”. Why do you think that this shift is necessary, and how did you read visual material differently to avert this notion?

Mika Natif: I believe that the shift in perspective was necessary in order to emphasize the agency of Mughal artists and patrons regarding the artistic relationship between European and Mughal painting. It seems that nobody was truly asking the question of why in the 1580s-1590s the Mughal elites – patrons and artists – would be even interested in incorporating Renaissance and Christian materials into their own creations, and what would these images mean for them.

Until very recently, the art historical discourse was shaped by a Eurocentric, not to say chauvinistic, agenda. Scholars have regarded the phenomenon as an “influence” of European and Catholic art on Mughal painting. The term “influence” alludes to imbalanced power relationships in which the “influencer” appears active and powerful and the party being “influenced” is passive and therefore weaker. My intervention challenges such a paradigm that casts these Mughal paintings as essentially derivative of Renaissance art and I move away from binary views of artistic exchanges. In the book, I demonstrate how these innovative visual changes were grounded in the new Mughal policy of sulh-i kull (‘universal conciliation’ or ‘peace with all’) and the formation of a multivalent empire with global aspirations.

SR: Your emphasis on parsing, selection, adaption and repurposing restores agency to the Mughal patron and artist. This positions Mughal visual culture as an intellectual tradition in its own right, and the ateliers as a site of knowledge production. Are there textual sources that refer to these practices, and do we see a similar reworking of the “oriental arts” in the courts of early modern Europe?

MN: Mughal textual sources can be allusive sometimes, and I often find myself reading between the lines. On the other hand, we should examine them critically and not accept immediately everything they say at face value. Ideally, as an art historian, I try to create a balance between textual and visual sources and pay attention to the ways they support or contradict one another. For example, Abu’l Fazl, the court chronicle, describes the ways in which paintings were inspected and evaluated every week by the Emperor and the head of the royal library. From his description we may learn of the close attention to details under which works of art were scrutinized. Did Akbar really examine paintings every week? Most likely not. After all, there were times that he was on the move, dealing with military campaigns or suppressing rebellions in the empire. However, Abu’l Fazl’s description of this close examination correlates to what I see within the works of art themselves: great attention to details that can only be achieved through intricate processes of parsing and selecting.

As for similar processes on the European side, the works of Rembrandt are a good example. Gary Schwartz gave a fascinating paper on his “Mughal series” a few months ago.

SR: In your book, you define “Mughal Occidentalism”, with reference to “international cosmopolitanism and a politics of cultural superiority on the part of the Mughals.” While scholars like Ebba Koch have written on Mughal cosmopolitanism in material culture, the politics of cultural superiority of aesthetics in a global/transcultural context seems like a new area of enquiry. Could you elaborate on the specificities of the cultural competition?

Jahangir with a globe- a favourite self-image of Mughal sovereignty and transculturality of the emperor. This painting is housed in the Chester Beatty library, Dublin.

Jahangir with a globe- a favourite self-image of Mughal sovereignty and transculturality of the emperor. This painting is housed in the Chester Beatty library, Dublin.

MN: Mughal claims of cultural superiority can be seen in textual sources, as has been demonstrated by the works of historians Muzaffar Alam, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, and Corrine Lefèvre. These attitudes are also visible in several incidents linked to paintings. For example, when Sir Thomas Roe, the English ambassador under King James I, visited Jahangir’s court, he brought a painting as a gift. When he was asked and then failed to identify some of the figures in the picture, the Ambassador was reprimanded by the Mughal Emperor. On another occasion, Jahangir put Roe’s cultural abilities into test. He showed the Englishman five images, one original and four copies, of a European painting that Roe himself brought as a gift to Jahangir, and asked him to identify the original. Roe, of course, failed to do so, to the delight of the Mughal Emperor.

Other modes of artistic competition can be seen in the works of Abu’l Hasan, Ruqaya Banu, Nini and others.

SR: Both “Orientalism” and “Occidentalism”, like anyother ‘ism’, have been in the eye of the storm in the academy for years. How have your colleagues and fellow art historians responded to “Mughal Occidentalism”?

MN: So far [I] have been getting wonderful responses from colleagues in various fields. I think that the book bridges a gap in scholarship on pre-modern South Asia and initiates a new dialogue between Renaissance specialists and historians of Islamic art.

SR: Coming to your fascinating work on micro-landscapes in Mughal paintings, especially from the Akbari atelier, would you tell us how you began working on background narratives and receding landscapes?

MN: When you spend so much time looking at illustrated manuscripts and paintings from the Akbar period, one cannot resists delving into the amazingly intricate and idyllic landscape features that appear in so many pictures from the 1580s-1590s. And then it makes you think about what is represented in these panoramas? Who are these figures? And geographically and temporally speaking, where all of this is located?

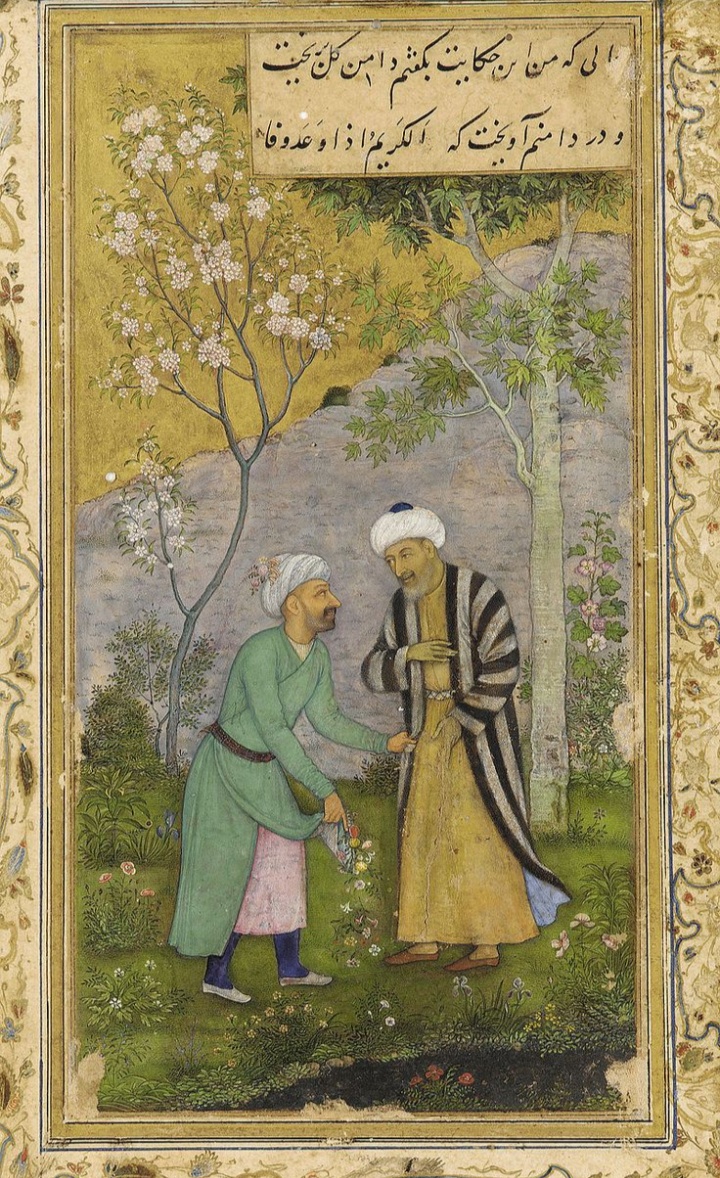

Sādi in a rose garden with his friend, painted by Govardhan, from a Gulistān manuscript. Natif reads homoeroticism in the metaphors and visual translations of Persian poetry. The folio is currently in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian.

Sādi in a rose garden with his friend, painted by Govardhan, from a Gulistān manuscript. Natif reads homoeroticism in the metaphors and visual translations of Persian poetry. The folio is currently in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian.

SR: In your study of landscape narratives, you draw beautiful connections between man and nature on one hand, and the notions of civility, justice and akhlaqi literature on the other. How does the idyllic, agrarian village, and the urbane Mughal metropolis come together in Akbari paintings?

MN: In the landscape painting, Mughal artists were masterful in portraying harmonious and balanced settings of the built world and the cultivated natural realm, related to Mughal urbanism and garden tradition. From a reading of Mughal literary sources about cities, topographical descriptions, and poetry in praise of urban centers, a geographical identity is revealed, which is manifested in the creation of micro-architecture landscapes in paintings. The particular time in which these vignettes appear, the 1590s, has a direct link to the crystallization of Akbar’s policy of the sulh-i kull and his striving to achieve balance and harmony among all subjects in the empire. These idyllic and intricate urban landscapes in the background of paintings reflect the Mughals’ sense of pride and ownership toward Hindustan and the reaffirmation of their just rule.

SR: You have also made significant contributions to the literature on sexuality and eroticism in art. At a time when global movements to acknowledge and decriminalise queerness and multifaceted sexualities is taking place, how does writing on premodern sexualities aid or enrich contemporary movements? Do you believe that academics have a greater responsibility leaning towards activism, especially if their research resonates with contemporary concerns?

MN: I hope that learning about pre-modern eroticism and sexuality and their role in art, poetry, literature and beyond, would help to contextualize and normalize such ideas. I also would like to believe that studying the Humanities may bring openness and tolerance towards others. This is where I see the role of academia in becoming a responsible and active agent with regard to contemporary concerns.

SR: As a specialist of ‘Islamic art’, who focuses on the transcultural worlds of ‘Muslim societies’, what does teaching art history mean to you in an age of seemingly ceaseless strife and disharmony? Do you see art history, and more importantly the act of teaching, as powerful engagements to battle the divisive hatred poured by the state and media?

MN: I am a great believer in education and learning. I think, as human beings, we are constantly in a state of learning. This is not something that stops once you graduate from school or university. Learning is a central part of living in the world, being open to great ideas, innovations, technology, and even smaller niches like cuisine and cinema. Teaching students to adopt this perspective and become critical thinkers is crucial, and I strive to do that through art history.

SR: In India, the ruling government is propagating a virulent form of nationalism, that is exclusive and predatory to say the least. A project of rewriting of the nation’s history based on notions of purity and indigeneity, and a complete erasure of hybridity or diversity is being orchestrated. Why, do you think, ‘transculturality’ poses an alarming threat to totalitarian politics, and how can academics and scholars make a public intervention at this point, outside the university departments and academic circles?

MN: Thinking about the Mughals and their policy of sulh-i kull, I believe that accepting ideas of transculturality means being self-secure, self-assured and comfortable, without feeling threatened by the existence of others or “otherness”. Hence, transculturality comes from a position of great strength. It is also the place in which curiosity and inquisitiveness, which are notable signs of intelligence, come into play.

SR: Your current book project focuses on the portraits of Mughal women, c.1590-1660. We have recently seen a proliferation of works on Mughal women and gender politics, for instance the writings of Lisa Balabanlilar and Ruby Lal. How did you decide to work on women’s portraiture, and what should we look out for in your upcoming book?

MN: It’s actually very simple. In the last chapter of Mughal Occidentalism I focused on portraits of the Mughals. My initial thought was to include a section on female portraits and their relationship to European art. However, as work progressed, I realized that this was a bigger and more complicated issue that requires its own publication. There is a lot of “house cleaning” to do, and the topic is very exciting and timely. I am having a lot of fun with the material!

Read more:

Remembering the Mughals with Catherine B Asher

What is it Like to Live Without the Mughals?

Fireworks and Firearms: The Festival of Lights in the Mughal Court