With Independence Day right around the corner, the Indian Cultural Forum is doing a series on the ideas that built India. From national movements to regional resistances, there have been multiple ideologies and leaders who’ve shaped the country’s desire for sovereignty and the post-Independence period. In the coming weeks we will attempt to bring together writing on many of these leaders and what legacies they have left us. As Independence Day approaches there will be a singular and deafening narrative built on hyper-nationalism. Instead, ICF will be publishing the many ideas, some contrary to each other, that actually lead to the formation of a free nation.

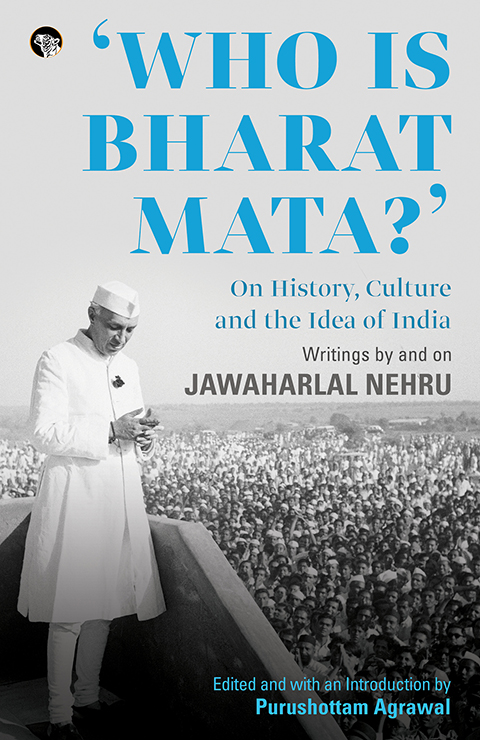

Edited by Purushottam Agrawal, ”’Who is Bharat Mata?’: On History, Culture and the Idea of India” is a collection of writings and speeches by and on Nehru. It shows us the mind—the ideology, born of experience, observation and deep study—behind Nehru’s democratic and inclusive idea of India. It is a book of particular relevance at a time when “nationalism” and the slogan “Bharat Mata ki Jai” are being used to construct a militant and purely emotional idea of India that excludes millions of residents and citizens. The following is an excerpt from the chapter “Culture, Literature and Science”.

In this speech delivered at the opening ceremony of the Fuel Research Institute, Digwadih, on April 22, 1950, Jawaharlal Nehru advocates the development of scientific temper, which seemed to be missing from society at large, including the scientists themselves. He also asks people to understand science not as a destroyer of nature, but something that seeks to uncover the secrets of nature to utilise them for the benefit of humanity; to see the active principle of science as discovery.

The Spirit of Science

(Speech at the opening ceremony of the Fuel Research Institute, Digwadih, 22 April, 1950)

In the course of less than four months, we have put up, declared open or are going to declare open three national laboratories. I suppose before this year is out some more national laboratories will also be started. This is a great venture testifying to the faith which our scientists and, I hope, our Government have in science. I suppose the putting up of fine and attractive buildings does some service to science; nevertheless, buildings do not make science as Dr Raman has often reminded us. It is human beings who make science, not bricks and mortar. Properly equipped buildings, however, help the human being to work efficiently. It is, therefore, desirable to have these fine laboratories for trained persons to work in and for persons to be trained for future work.

You, Sir, referred to the spirit of science. I wonder what exactly that spirit is and to what extent we agree or differ in our ideas of it. Is science, as is often supposed, a handmaiden to industry? It certainly wants to help industry, though not merely for the sake of helping industry but also because it wants to create work for the nation, so that people may have better living conditions and greater opportunities for growth. That I suppose will be agreed to but there is something more to it. What ultimately does science represent?

You, Sir, just referred to scientists declaring war on nature. May I put it in a different way? We seek the cooperation of nature, we seek to uncover the secrets of nature, to understand them and to utilize them for the benefit of humanity. The active principle of science is discovery. Now, what is, if I may ask, the active principle of a social framework or society? Usually, it stands for conservatism, remaining where we are, not changing and carrying on, though, of course, with some improvement and further additions. Nevertheless, it is a principle of continuity rather than of change. So, we come up against a certain inherent conflict in society between the coexisting principles of continuity and of conservatism and the scientific principle of discovery which brings about change and challenges that continuity. So the scientific worker, although he is praised and patted on the back, is, nevertheless, not wholly approved of, because he conies and upsets the status quo of things. Normally speaking, science seldom really has the facilities that it deserves except when some misfortune comes to a country in the shape of war. Then everything has to be set aside and science has its way, even though it is for an evil purpose.

It is interesting to see this conflict between the normal conservatism of a static society and the normal revolutionary tendency of the scientist’s discovery which often changes the basis of that society. It changes living conditions and the conditions that govern human life and human survival.

I take it that most people who talk glibly of science, including our great industrialists, think of science merely as a kind of handmaiden to make their work easier. And so it is. Of course, it does make their work easier. It adds to the wealth of the nation and betters conditions. All this science does do. But surely science is something more than that. The history of science shows that it does not simply better the old. It sometimes upsets the old. It does not merely add new truths to the old ones but sometimes the new truth it discovers disintegrates some part of the old truths and thereby upsets the way of men’s thinking and the way of their lives. Science, therefore, does not merely repeat the old in better ways or add to the old but creates something that is new to the world and to human consciousness.

If we pursue this line of thought, what exactly does the spirit of science mean? It means many things. It means not only accepting the fresh truth that science may bring, not only improving the old but being prepared to upset the old if it goes against that spirit. It also means not being tied down to something that is old because it is old, because we have carried on with it but being able to accept its disintegration; it means not being tied down to a social fabric or an industrial fabric or an economic fabric if it goes against the new discovery.

Whatever they may say, most countries normally do not like to change. The human being is essentially a conservative animal. He is used to certain ways of life and anyone trying to change them meets with his disapproval. Nevertheless, change comes and people have to adapt themselves to it; they have done so in the past. All countries, as I said, are normally conservative. But I imagine that our country is more than normally conservative. It is for this reason that I venture to place these thoughts before you. I find a curious hiatus in people’s thinking. I find it even in the thinking of scientists who praise science and practise it in the laboratory but discard the ways of science, its method of approach and the spirit of science in everything else they do in life. They become completely unscientific. If we approach science in the proper way, it does some good and there is no doubt that it will always do some good. It teaches us new ways of doing things. Perhaps, it improves our conditions of industrial life but the basic thing that science should do is to teach us to think straight, to act straight and not to be afraid of discarding anything or of accepting anything, provided there are sufficient reasons for doing so. I should like our country to understand and appreciate that idea all the more, because in the realm of thought our country in the past has, in a sense, been singularly free and it has not hesitated to look down the deep well of truth whatever it might contain. Nevertheless, in spite of such a free mind, our country encumbered itself to such an extent in matters of social practice that its growth was hindered and is hindered in a hundred ways even today. Our customs are just ways of looking at little things that govern our lives and have no significant meaning. Even then, these customs come in our way. Now that we have attained independence, there is naturally a resurgence of all kinds of new forces, both good and bad: good forces are, of course, liberated by a sense of freedom but along with them there are also a number of forces which, under the guise of what people call culture, narrow our minds and our outlook. These forces are essentially a restriction and denial of any real kind of culture. Culture is the widening of the mind and of the spirit. It is never a narrowing of the mind or a restriction of the human spirit or of the country’s spirit. Therefore, if we look at science in the real way and if we think of these research institutes and laboratories in a fundamental sense, then they are something more than just little ways of improving things and of finding out how this or that should be done. Of course, we have to do that, too. But these institutes must gradually affect our minds, not only the minds of the young men and young women who would work here but also the mind of others, more specially the minds of the rising generation, so that the nation may imbibe the spirit of science and be prepared to accept the new truth, even though it has to discard something of the old. Only then will this approach to science bear true fruit. It is because we attach importance to these research institutes that we have ventured to ask you, Sir, Mr President, to take the trouble to come all the way here to open this third of our great national laboratories and we are very grateful to you that you have taken the trouble to do so. I am sure that your visit here and the visits of the many distinguished scientists will prove a blessing to this institute. Besides, it will help to draw people’s attention not only to the external applications and implications of science but to its real value which lies in widening the spirit of man and thereby bettering humanity at large.

Read more:

Scientific temper is of fundamental importance to the acquisition and transfer of knowledge”

The Search for India

Hindu and Muslim Communalism

The Cunning of Caste

The Mechanism of Caste