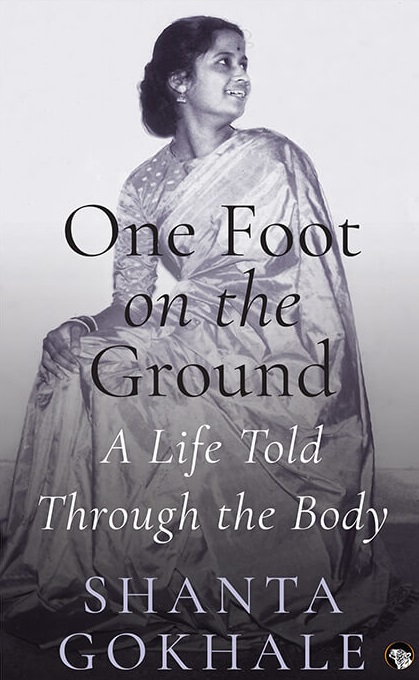

In this extraordinary autobiography, Shanta Gokhale—writer translator and one of India’s most illuminating cultural commentators—traces the arc of her life over eight decades through the progress of her body, as it grows, matures and begins to wind down. Starting with her birth in 1939–in philosophic silence, till the doctor’s slap on her bottom made her brawl–she recounts her childhood, youth and middle and old age in chapters built around the many elements and processes of the physical self: tonsils and adenoids, breasts and misaligned teeth; childbirth and fluctuating weight, cancer and bunions.

Told with effortless humour and candour, One Foot on the Ground is the story of a life full of happiness, heartbreak, wonder and acceptance.

The following are excerpts from the chapters “The Babies Are Born and How!” and “Hair and Heart” of the book.

Image courtesy: Speaking Tiger

Image courtesy: Speaking Tiger

I discovered translation as a serious and deeply satisfying occupation in Vizag. Satyadev Dubey first pushed me into it. We were staying in a place called New Entry Camp, a kind of halfway house to a proper accommodation. The house was built like a train with four sequential compartments, a breezy corridor running their full length facing a large garden, and a kitchen attached at right angles to the fourth compartment, by a covered passage. I wasn’t doing much with myself except writing fiction in Marathi, directing plays for the local Maharashtra Mandal and playing badminton. In the midst of this leisurely life came Dubey’s letter. Polite as always, he wrote, ‘You are vegetating there. You’ve become a cow. Do some work. Translate the play that’s coming to you by separate post.’ The play was poet-playwright C.T. Khanolkar’s Avadhya, hailed by Marathi theatre’s reigning drama critic Madhav Manohar as ‘the first adult play’ in Marathi and condemned by the cultural orthodoxy as obscene. The play exposed the hypocrisies of middle-class morality with brutal insight. Three men in a lodge are informed by the room boy that a peephole has been obligingly made behind the calendar on the wall through which they may, if they so wish, watch the young couple next door make love. The men were utterly revolting; but converting Khanolkar’s sharp dialogue into something equally punchy in English gave me a high such as I had not experienced before. Dubey liked the translation and sent it to his friend Rajinder Paul in Delhi, editor of the theatre magazine Enact. Avadhya, The Invincible, was the first of many of my translations that Enact was to publish.

Comrade Godavari Parulekar, a friend of the family, had written a book about the Warlis of Dahanu and the surrounding areas amongst whom she had worked and for whose rights she had fought for many years. The book was called Jenwha Manus Jaagaa Hoto—When Man Awakens. A fellow comrade had translated it into English, but Godutai was not happy with the translation. She sent me the manuscript to correct. The translation was so bad, I did a fresh translation instead. My version got published, but it did not carry my name. It carried the original translator’s name. It would have been awkward for Godutai to explain to her colleague what had transpired with his draft. A reward more precious than having my name on the book lay in having had the chance to translate it in the first place. Translation forces you to engage intimately with a work; and this was a book about people whom I had known from childhood. Dahanu was my mother’s home. That is where I was born. That was where I had spent many summer holidays, surrounded by Warlis who worked in my grandfather’s home and factory. To know the oppression and exploitation that they had endured was to know the other, darker side of the lives of these people whom I adored.

When I chose to do English Literature in England, Mother had asked me how I intended putting my knowledge to use back home. I had said I would teach. ‘That is one way,’ she had said. ‘But there’s another which you must consider. Translate the best Marathi literature into English.’ With Avadhya and Jenwha Manus Jaagaa Hoto, I had set off on that path.

[…]

It is said that if you put two Marathis together on a desert island, they’ll do a two-hander play.

Ignoring Mr X’s dismissal of the histrionic abilities of Glaxo’s workforce, I had sent word around the following morning to say I was starting a drama group. Ten men and women from the factory floor and offices had registered during tea and lunch break that day and more were on their way. I worked out a plan for lunchtime plays which ensured that neither actors nor audience went without lunch or entertainment and were still back at their desks or conveyor belts on the dot. We couldn’t afford to have managers and supervisors complain.

Glaxo had three staggered lunch breaks of forty-five minutes each. I chose playscripts that could be pared down to thirty minutes. Employees would eat their lunch in ten minutes, rush to the auditorium, see our play and still have five minutes to return to their workplaces. We would stage five shows over two days to cover all lunch breaks. The employees came in droves and went away asking for more. I cannot claim they worked better for having seen a play in their lunch break; but seeing a play altered their view of the company. They had regarded Glaxo as a stodgy, po-faced employer. Now they conceded it had some human features.

Even before we put up our first play, casteism showed its dark, dank, narrow mind. A true-blue Maratha who had been one of the first I had cast for the play said to me, ‘Why have you cast Sanjay?’

‘Because he’s a very good actor.’ ‘But you know what he is?’ ‘What?’

‘Not one of us.’

‘I don’t know what that’s supposed to mean. But he is in the play.’

‘You might find others withdrawing.’ ‘Just too bad if they do.’

Nobody withdrew. Not even the true-blue Maratha.

News got around about our conversation. A clerk stopped by my desk casually and said, ‘These Marathas think no end of themselves. And here’s we, brahmins, who don’t dare say a word.’

Two Dutch journalists had come to interview me about caste. Their assumption was that it was a thing of the past in cities. I told them my Glaxo story. They made me repeat it twice before they were willing to believe it. When they sent me a translation of their story, I found I was the only one who had said caste was alive and kicking in Bombay. Everybody else had said it was dead.

Read more:

The Tribe, Tribalism and The Nation

“It’s often assumed that one’s a Dalit if their research is on Ambedkar”

‘Home’ as a site of oppression: Paul Chirakkarode’s ‘Pulayathara’