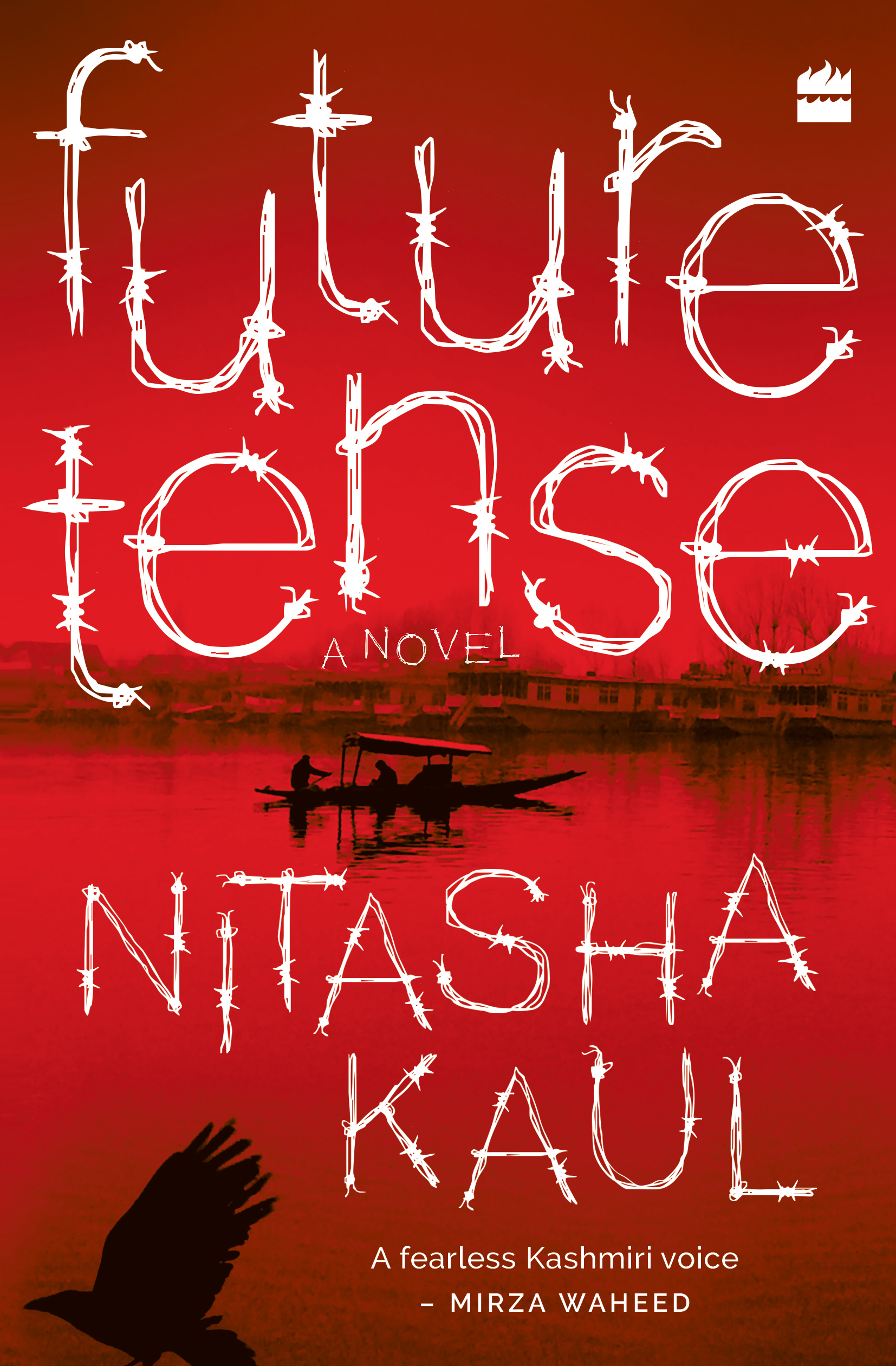

Intersecting the paths of Fayaz, the son of a former militant, his nephew Imran, and Shireen, the granddaughter of a spy, Nitasha Kaul, in her novel Future Tense, traces the competing trajectories of modernity and tradition, freedom and suffocation, and the possibility of bridging the stories of different kinds of Kashmiris.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

One April afternoon, the news from Kashmir became a louder ripple in the world at large. From the newspapers to the television channels, in the Valley and in India and in the rest of the world, were splashed the images of a Kashmiri man tied to the front of a jeep that led an Indian Army convoy. People pieced together the details over the coming days. There were by-elections in progress in a constituency where a paltry single-digit percentage of people who were eligible to vote had come out to cast their ballots. This was not unusual in itself since the arithmetic of Indian democracy could be a cruel joke in Kashmir. But something else transpired that day, which made it through the noise of world affairs and demonstrated to the world that there was an infinitely elastic range of things that could now be compatible with a place still being referred to as democratically governed. The Kashmiri people had known this all along, but now many Indians and others around the world were forced to take notice too.

When he saw the images and the video of the use of his fellow Kashmiri as a human shield, Imran wanted to go out and pelt every stone he could lay his hands on. Fayaz and Rehan were chillingly reminded of their childhood nightmares. Gul told his terrified family that this was nothing new. Like many other young boys, he himself had been used as a civilian human shield during the search operations years ago. Many men remembered how, back in the early years of the uprising, they were forced by the army to go into buildings that were to be checked for the presence of militants. Zeenat prayed, reaching the resolve that she would atone for her inability to fight the oppression by saving a life. Ifra composed letters to newspapers. Rehan wrote poetry in a drunken haze after his conversation with Saima about how miserable it was to be born a helpless Kashmiri. Saima went online to battle the xenophobic Indian trolls who could see nothing wrong with what had happened. Shireen realized that this was not an abstract tragedy for her either. This was the display of vile inhumanity that should offend a human being regardless of their identity. Men could be dolls too. She wondered how the soldiers could follow orders that made them do such things. Then, she realized that humanity lived in a world where the holocaust was not even a hundred years old.

Bichor lay on the floor at home, wishing Rafiq was around to blow up the tyrants. He stared at the backs of the dummies hanging in the window in front of him. Tied with plastic threads, the three silhouettes were suspended from the curtain rail above. Bichor’s mother was at the neighbour’s house and his father was sleeping nearby. He had heard that the clashes between the police and the protestors were spreading across the Valley. The images from the television reports played in slow motion inside his head.

A young civilian Kashmiri man goes out to vote, risking the disapproval of many around him who would die before confirming Indian rule in Kashmir through the visit to a polling booth. He casts his ballot and comes out. The soldiers of the Indian Army pick him up and truss him to a jeep. He is affixed to a spare tyre at the front. He wears a grey pheran over blue jeans, and his shoes are brown. Two lines of ropes are tied around his body to secure a white sheet of paper that warns other Kashmiri people not to protest. A triangular red flag flutters at the side of the vehicle. An Indian soldier stands imposingly behind the tied man, the upper half of his body visible through the sunroof. In a supposed spectacle of unabashed might, the soldier towers over a man who cannot move. Behind that jeep is a convoy of armoured and weaponized trucks. The Kashmiri man sits with his legs parted; he’s tied to the jeep at the very front and has the look of a stone on his face. The entire horrific procession passes the shuttered shops on muddy roads lined with long corrugated tin sheets on either side.

We wanted to defend our lives and pass safely through the troubled area, said the army major in charge. The man was fomenting trouble and directing stone-pelters, they added.

Bichor could not sleep that night. He was clear that it was better for Kashmiri men to die with honour than to be tied to the fronts of jeeps. Whatever difference did education make? Didn’t those Indian Army people go to schools and colleges? And had it taught them humanity?

‘Human shield,’ what a word in what a world!

How could human beings be treated like objects? He could not get this question out of his mind. How could it be possible not to see the difference between people and things? Even the most illiterate person could tell you what a thing was and how it was different from a person. Even a child could tell you that. What was it about a uniform that made people become unable to see something as obvious as that? When the powerful saw the powerless, maybe they saw them simply as human outlines — as dummies — to be used and discarded.