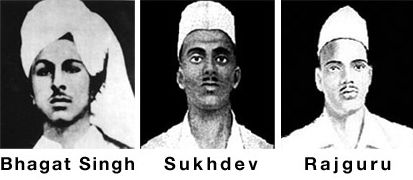

Eighty-six years ago, three young men were hanged in Lahore for ‘waging war against the state’ by the colonial government in India. All three men belonged to the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), an organisation that aimed at liberating the people of India from its colonial masters, the British Crown. Several young men and women joined this struggle in various capacities, and today, we associate the slogan Inquilab Zindabad with their remarkable story. The story of revolutionary freedom fighters continues to appeal to the young and passionate amongst us. But these three men and their comrades were young but firm, passionate but rational, and, most of all, honest in their aspirations for a free country. Today, everything that remains of their correspondence and the stories inscribed in history needs to be revisited. Their actions, sacrifices and courage commended them a place in history. Let us look at the concerns that dominated the minds of such extraordinary people in their short but momentous lives.

As a young 16 year old student in 1923, Bhagat Singh wrote an essay on the importance of language in imbuing ‘Indianness’ and unity amongst the people of India. His earliest understanding of unity and national identity stressed the need to break away from communal polarisation in order to communicate, comprehend and co-exist in the subcontinent. Precociously, he claimed, “Countries have followed the direction determined by the flow of their literature. Every nation needs literature of high quality for its own upliftment. As literature of a country attains new heights, the country also develops.” As a teenage boy, this essay won him a prize and was later published in Hindi magazines as well. But by then, Bhagat Singh’s worldview had undergone a radical change. With it, his language changed dramatically as well. Three years later, in 1926, in an article signed simply ‘Ek Punjabi Yuvak’ or a Punjabi Youth, he wrote about the hanging of six Babbar Akalis in the Lahore Central Jail on the day of Holi. Pained by the indifference of the people, he wrote, “The city was still celebrating. Colour was still being thrown on the passers-by. What a terrible indifference. If they were misguided, if they were frenzied, let them be so. They were fearless patriots, in any case. Whatever they did, they did it for this wretched country. They could not bear injustice. They could not countenance the fallen nation.” Here, he tries to weigh the actions of the Babbar Akalis in the eye of the law and of society. The heroic story of the Akalis deeply influenced the youth of Punjab. But what seems to have moved Bhagat Singh the most was their fearlessness in the face of death.

In the years that followed, Bhagat Singh moved closer to the movement brewing against the colonial state. The formation of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association was followed by participation in agitations and propaganda work among the youth in the country. The brutal attack on Lala Lajpat Rai that subsequently led to his death provoked a strong sense of rage within the youth. This rage found voice in the killing of a British police officer, JP Saunders. Taking responsibility for the killing, a notice pasted on the walls of Lahore in December 1928, signed as ‘Balraj’, openly declared the inevitability of a revolutionary movement to change the existing political condition. It ended with this pronouncement, “Sorry for the bloodshed of a human being; but the sacrifice of individuals at the altar of the Revolution that will bring freedom to all and make the exploitation of man by man impossible, is inevitable. Long Live the Revolution!”

On April 8th 1929, protesting the implementation of the draconian Public Safety Bill and the Trade Disputes Bill in the name of reforms by the colonial government, BK Dutt and Bhagat Singh showered copies of a pamphlet on the floor of the Central Assembly Hall after tossing two bombs in the Assembly corridors in New Delhi. The pamphlet read, “Let the representatives of the people return to their constituencies and prepare the masses for the coming revolution, and let the Government know that while protesting against the Public Safety and Trade Disputes Bills and the callous murder of Lala Lajpat Rai, on behalf of the helpless Indian masses, we want to emphasise the lesson often repeated by history, that it is easy to kill individuals but you cannot kill ideas. Great empires crumbled while the ideas survived, Bourbons and Czars fell, while the revolution marched ahead triumphantly.”

On the 6th of June, when deposing before the court on charges of attacking the institutions of the state, Mr Asaf Ali, representing both BK Dutt and Bhagat Singh, read out the duos response, “We humbly claim to be no more than serious students of the history and conditions of our country and her aspirations. We despise hypocrisy. Our practical protest was against the institution, which since its birth, has eminently helped to display not only its worthlessness but its far-reaching power for mischief. The more we have been convinced that it exists only to demonstrate to the world Indian's humiliation and helplessness, and it symbolises the overriding domination of an irresponsible and autocratic rule. Time and again the national demand has been pressed by the people's representatives only to find the waste paper basket as its final destination.”

On being asked to explain what they mean by ‘revolution’, they answered, “By 'Revolution' we mean that the present order of things, which is based on manifest injustice, must change. Producers or labourers in spite of being the most necessary element of society are robbed by their exploiters of the fruits of their labour and deprived of their elementary rights. The peasant, who grows corn for all, starves with his family, the weaver who supplies the world market with textile fabrics, has not enough to cover his own and his children's bodies, masons, smiths and carpenters, who raise magnificent palaces, live like pariahs in the slums. The capitalists and exploiters, the parasites of society, squander millions on their whims. These terrible inequalities and forced disparity of chances are bound to lead to chaos. This state of affairs cannot last long, and it is obvious, that the present order of society in merry-making is on the brink of a volcano….The whole edifice of this civilisation, if not saved in time, shall crumble. A radical change, therefore, is necessary and it is the duty of those who realise it to reorganise society on the socialistic basis. Unless this thing is done and the exploitation of man by man and of nations by nations is brought to an end, sufferings and carnage with which humanity is threatened today cannot be prevented. All talk of ending war and ushering in an era of universal peace is undisguised hypocrisy.”

Their protest did not end even after being sent to jail during the course of the widely-known Assembly Bomb Case of 1929. In another letter dated 24th June, the duo demanded to be recognised and treated as ‘political prisoners’. This they defined as, “By 'Political Prisoners', we mean all those people who are convicted for offences against the State, for instance the people who were convicted in the Lahore Conspiracy Cases, 1915-17, the Kakori Conspiracy Cases and Sedition Cases in general.”

In the eve of the movement of 1930-31, Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt sent an inspiring message to the Second Punjab Students’ Conference in Lahore in October 1929 stating, “The youth will have to bear a great burden in these difficult times in the history of the nation…. The youth will have to spread this revolutionary message to the far corners of the country. They have to awaken crores of slum-dwellers of the industrial areas and villagers living in worn-out cottages, so that we will be independent and the exploitation of man by man will become an impossibility.”

When dealing with the colonial legal system, Bhagat Singh's ingenuity and rational argument shine through his letters. In a statement emphasising the importance of motive of action when judging the offence of the accused, Bhagat Singh succinctly argued, “If we ignore the motive, the biggest general of the wars will appear like ordinary murderers; revenue officers will look like thieves and cheats. Even judges will be accused of murder. This way the entire social system and the civilisation will be reduced to murders, thefts and cheating. If we ignore the motive, the government will have no right to expect sacrifice from its people and its officials. Ignore the motive and every religious preacher will be dubbed as a preacher of falsehoods, and every prophet will be charged with misguiding crores of simple and ignorant people.” Reiterating their emphasis on the motive of their actions, the statement ends with, “We have not come before you to get our sentences reduced. We have come here to clarify our position. We want that we should not be given any unjust treatment, nor should any unjust opinion be pronounced about us. The question of punishment is of secondary importance before us.”Even from within the walls of the jails, Bhagat Singh and his comrades continued their struggle as independent, rational and progressive minds, to be heard, recognised as undertrial political prisoners and, more than anything else, as human beings. Refusing to attend the court proceedings for the Lahore Conspiracy Case after denial of basic facilities within court, denial of legal support, and even denial of newspapers in English and in other vernacular languages within jail, they strongly argued for the basic rights of all before the eyes of the law.

After being repeatedly ignored by the courts and the institutions of the state after demanding the right to basic facilities within jail, Bhagat Singh and his comrades reiterated their demands to the Special Magistrate in the Lahore Conspiracy Case before resuming their hunger strike. In this letter we see Bhagat Singh envisioning himself as part of a larger, longer history where thousands upon thousands will take up the fight for freedom after he is gone. It says, “The government, by its dilatory attitude and the continuation of vindictive treatment to political prisoners, has left us no other option but to resume the struggle. We realise that to go on hunger strike and to carry it on is no easy task. But let us at the same time point out that India can produce many more Jatins and Wagias, Ran Rakshas and Bhan Singhs. (The last two named laid down their lives in the Andamans in 1917 – the first breathed his last after 63 days of hunger strike while the other died the death of a great hero after silently undergoing human tortures for full six months.)”

When the colonial government attempted to by pass the court of law by promulgating the Lahore Conspiracy Case Ordinance that ensured that the accused need not appear in court, thus, prohibiting Bhagat Singh and his comrades from using the court as a platform for propagating their aims and objectives, Bhagat Singh wrote a letter to the Governor-General of India in May 1930 exposing their motives. In a remarkable letter that laid bare the desperation of the colonial government, Bhagat Singh wrote, “We had been from the very beginning pointing out that this existing law was a mere make – believe. It could not administer justice. But even those privileges to which the accused were legitimately and legally entitled and which are given to ordinary accused, could not be given to the accused in political cases. We wanted to make the government throw off its veil and to be candid enough to admit that fair chances for defense could not be given to the political accused. Here we have the frank admission of the Government. We congratulate you as well as your government for this candour and welcome the Ordinance….Inspite of the frank admission of your agents, the Special Magistrate and the Prosecution Counsels, as to the reasonableness of our attitude throughout, you had been confused at the very thought of the existence of our case. What else is needed to assure us of our success in this fight?”

In a letter drafted by Bhagat Singh in May 1930 to be read in court on the behalf of four (J.N. Sanyal, B.K.Dutt, Dr. Gayal Prasad, Kundan Lal) of the accused in the Lahore Conspiracy Case who simply refused to recognise the legitimacy of the British government in India, the signatories declared, “Such governments which are organised to exploit the oppressed nations, have no right to exist except by the right of the sword (i.e., brute force) with which they try to curb all the ideas of liberty and freedom and the legitimate aspirations of the people….We believe all such governments, and particularly this British government thrust upon the helpless but unwilling Indian nation, to be no better than an organised gang of robbers, and a pack of exploiters equipped with all the means of carnage and devastation. In the name of "law and order", they crush all those who dare to expose or oppose them….We believe that imperialism is nothing but a vast conspiracy organised with predatory motives. Imperialism is the last stage of development of insidious exploitation of man by man and of nation by nation.”

In the midst of their political struggle, they never lost sight of their larger goal. In January 1930, in court for a hearing in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, Bhagat Singh asked the magistrate to send word to the Third Communist International with hearty greetings on Lenin Day.

Meanwhile, when it came to his allies, the closest comrades and friends, Bhagat Singh, the political visionary is eclipsed by an inordinately humble human being. When his father filed a petition appealing for Bhagat Singh's innocence, he wrote an anguished letter to his father disturbed at what he saw as a betrayal. Bhagat Singh writes asking his father to respect his political decision and resolves to continue fighting for his principles. He says, “My life is not so precious, at least to me, as you may probably think it to be. It is not at all worth buying at the cost of my principles.”

In his iconic polemical text titled ‘Why I’m an Atheist’, Bhagat Singh looks at his own past, his changing views, and the consolidation of his principles. At one point in the essay, while remarking on the solace of god, Bhagat Singh reminds us of the importance of principles when he says, “Beliefs make it easier to go through hardships, even make them pleasant. Man can find a strong support in God and an encouraging consolation in His Name. If you have no belief in Him, then there is no alternative but to depend upon yourself.”

In the early correspondence between Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev, we see a remarkable relationship based on the urge to share candid opinions with the sincerity it deserves. When speaking of the relationship between ‘love’ and ‘sacrifice’ in 1929, he notes that, “…man must have the strongest feelings of love which he may not confine to one individual and may make it universal.” But the clearest instance of their honesty with each other is visible when, in 1930, Sukhdev writes to Bhagat Singh letting him know that he prefers to commit suicide than spend twenty years in jail. To this, Bhagat Singh responds with a sharp letter reminding him of the cost of standing by ones principles, “Apart from this, the comrades among us, who believe that they will be awarded death, should await that day patiently when the sentence will be announced and they will be hanged. This death will also be beautiful, but committing suicide – to cut short the life just to avoid some pain – is cowardice.”

In his final letter to BK Dutt in November 1930, Bhagat Singh said, “I am condemned to death, but you are sentenced to transportation for life. You will live and, while living, you will have to show to the world that the revolutionaries not only die for their ideals but can face every calamity. Death should not be a means to escape the worldly difficulties. Those revolutionaries who have by chance escaped the gallows for the ideal but also bear the worst type of tortures in the dark dingy prison cells.”

In a final polemical letter, when it appeared that the Congress was intent on compromise over struggle, Bhagat Singh wrote a letter addressed to all young political workers. In the strongly worded and critical letter he reminded the youth that, “I have said that the present movement, i.e. the present struggle, is bound to end in some sort of compromise or complete failure….I said that, because in my opinion, this time the real revolutionary forces have not been invited into the arena. This is a struggle dependent upon the middle class shopkeepers and a few capitalists. Both these, and particularly the latter, can never dare to risk its property or possessions in any struggle. The real revolutionary armies are in the villages and in factories, the peasantry and the labourers. But our bourgeois leaders do not and cannot dare to tackle them. The sleeping lion once awakened from its slumber shall become irresistible even after the achievement of what our leaders aim at.” He ended this crucial letter with an earnest hope for the youth of the country, “Crush your individuality first. Shake off the dreams of personal comfort. Then start to work. Inch by inch you shall have to proceed. It needs courage, perseverance and very strong determination. No difficulties and no hardships shall discourage you. No failure and betrayals shall dishearten you. No travails imposed upon you shall snuff out the revolutionary will in you. Through the ordeal of sufferings and sacrifice you shall come out victorious. And these individual victories shall be the valuable assets of the revolution.”

In his final iconic letter to the Governor of Punjab after he was charged with waging war against H.M. King George, the King of England and the state, Bhagat Singh lays out the political condition before the people of the country. He says, “Let us declare that the state of war does exist and shall exist so long as the Indian toiling masses and the natural resources are being exploited by a handful of parasites. They may be purely British Capitalist or mixed British and Indian or even purely Indian…. It may assume different shapes at different times. It may become now open, now hidden, now purely agitational, now fierce life and death struggle. … It shall be waged ever with new vigour, greater audacity and unflinching determination till the Socialist Republic is established and the present social order is completely replaced by a new social order, based on social prosperity and thus every sort of exploitation is put an end to and the humanity is ushered into the era of genuine and permanent peace. In the very near future the final battle shall be fought and final settlement arrived at… The days of capitalist and imperialist exploitation are numbered. The war neither began with us nor is it going to end with our lives.”

With these words, we see the transformation in thought and action, the spirit of struggle and the sincerity of the revolutionary sacrifices of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev and the countless others who laid down their lives for our freedom. It is only fitting to remember that eighty-six years later their words ring true, “The sword of revolution is sharpened on the whetting-stone of ideas.”