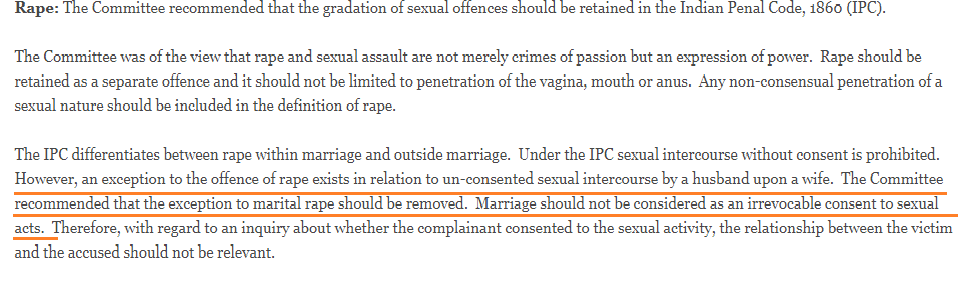

In the aftermath of the December 2012 Delhi gang-rape, the Justice Verma Committee was constituted to review the existing rape laws in India, and suggest amendments. The committee was of the view that rape is not a crime of passion but a brutal expression of power. Therefore, it is consent, and not the relationship between the victim and the accused, that should be relevant to the enquiry. The three-member committee pressed for the criminalisation of marital rape with immediate effect.

However, no concrete effort was seen on the part of the Supreme Court to implement this. In fact, what disrupted the implementation of this amendment in 2013, was the Government’s response that marital rape does not qualify as sexual offence because marriage presumes consent. Vice-President of India M Venkaiah Naidu, the then Chairman of the standing committee on home, responded to it by saying, “If litigations are allowed, then the family system will be disturbed.”

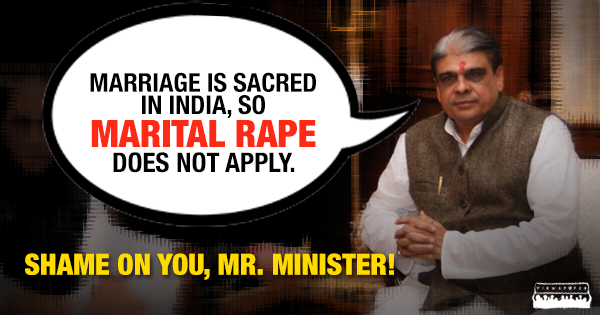

In 2015, the debate re-surfaced in the media when a United Nations Populations Fund survey reported that around 75 percent of Indian women are victims of marital rape. The response by Haribhai Parathibhai Chaudhary, Minister of State for Home, in this respect, is still referred to as the standard excuse for dismissal of accountability for something as serious as marital rape,

“It is considered that the concept of marital rape, as understood internationally, cannot be suitably applied in the Indian context due to various factors, including level of education, illiteracy, poverty, myriad social customs and values, religious beliefs, the mindset of the society to treat the marriage as a sacrament.”

Recently, the Supreme Court clarified its position with regards to the existing clause in the penal code (IPC 375). Section 375 exempts married men from those incriminated for forcing themselves “wrongfully” on their wives. According to the court, only girls under 15 years of age can be considered potential victims of sexual offence within marriage.

In 2015, lawyers Fatima Quraishi and Kamlesh K. Mishra appealed to the Supreme Court to acknowledge marital rape as a crime, while representing a woman who had been allegedly subjected to brutal sexual assault by her husband. The young Muslim woman, who married her lover and converted to Hinduism for marriage, complained that her husband would repeatedly force himself on her, and beat her up anytime she refused him sex. She says that one time he pressed a pillow on her face while raping her by inserting objects like a torch in her vagina. Fatima Quraishi said that despite the heinousness of the case which “sends jitters down one’s spine”, the Supreme Court refused to address it as rape, and their plea was subsequently dismissed. The court's response was not what they had hoped for: "Since this is a petition by an individual, we would not like to intervene."

So far, a married woman can only file a complaint against abuse by her husband, or in-laws mostly through section 498A of the Indian Penal Code which broadly covers all forms of cruelty. Quraishi and Mishra were obligated to refer to the same clause as a last resort for their client, where all questions of her being sexually violated by her husband were obliterated, and only the cruelty associated with the act was acknowledged.

Oppositions to the inclusion of marital rape as an offence not only revolve around the arguments in favour of the preservation of the “sacred” institution of marriage, but also stem from the dangerous patriarchal notion that a law that criminalises marital rape can be easily abused or misused to incriminate innocent men. The SC bench discussing marital rape betrays this damaging mindset which is simultaneously oblivious, and suspicious of female sexuality and issues of consent. When questioned about the safety of women above 15 years of age their response was, “There are cases when college-going teens, below 18 years of age, engage in sexual activities consensually and get booked under the law. Who is going to suffer? The boy is not at fault. The punishment of seven years is too harsh.”

This attitude will prove to be extremely disempowering for those who tirelessly fight for the criminalisation of marital rape, to say nothing of the women, especially married women in the country, who suffer endlessly because of the rampant normalisation of rape and sexual assault by the institution of marriage, and the state which endorses, and sanctions it.