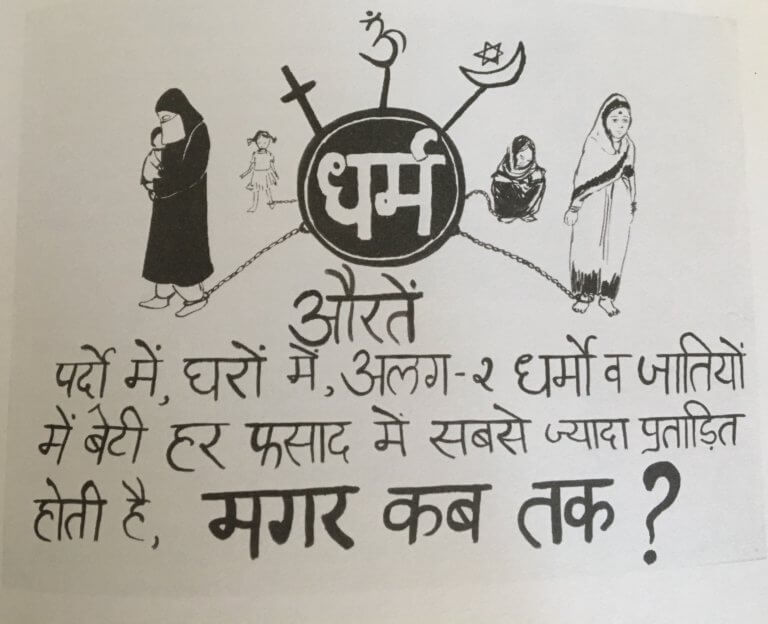

Struggles of women for dignity and rightful place in the world pervade all locations and religious communities. Sameena Dalwai, in her auto-ethnographic piece, offers testimony to the ongoing battle for gender justice.

Almost all discussions after the Triple Talaq judgement are missing the point. The issue is not about religion but about patriarchy and its various manifestations. Growing up in a Hindu-Muslim Socialist feminist household, I have stumbled upon the worlds of patriarchy everywhere.

The Triple Talaq judgement reminded me of Nafisa Athania, whose person and case loomed large over my childhood consciousness. A woman from the Chilia community hailing from Gujrat, she was married into an influential family in her native village. This was a typical agricultural household with a huge joint family, with an enormous amount of physical labour for the young daughters in law.

One day her husband marched into the house, stood before her and uttered “Talaq, Talaq, Talaq”. Chilias followed the Hanafi school of Islamic law that allowed Jubani or oral talaq. This instantly displaces a married woman from her matrimonial home. Nafisa returned to her father’s poor household, situated inside a dilapidated chawl in Mumbai, Jogeshwari.

She applied for visitation rights to meet her daughter and later, for custody. In the meantime, the husband had remarried but could not have more children. The whole Jamaat, i.e. the community Panchayat, turned against Nafisa when she refused to give up her daughter. The Court case went on forever. It was a most grueling affair during which Nafisa and her family were ruined by the power and money of her husband’s clan.

Her family was ex-communicated and their relationships with the biradari were severed. Her sister in law was made to return to her maika, leaving her husband and six children behind. Nafisa’s daughter was kept in a residential school by the Court order, where her father would pile her with expensive gifts. When she came of age, the daughter chose to go to her father, rather than to her poor harassed mother.

We saw Nafisa on our doorstep every now and then, in her black burkha. There would be a new painful development in her story but her spirit was still unbroken, fierce. Ultimately, she was running a household with extremely old parents, a heartbroken brother and his children and a crippled nephew who needed constant care, while pining for her own daughter.

She found some respite in the fact that the daughter was well looked after in her father’s rich household. Later, the daughter was married to her father’s brother’s son, which was a common practice. Everything would have been great – the father’s property would come to the daughter but would remain in the family. Alas, within a few years, her father died. Her husband, almost in response, married another woman. With a young daughter, Nafisa’s daughter faced a similar predicament as her mother had done, 20 years ago.

This tragedy formed many of my earlier impressions of Jubani or oral talaq and the plight of Muslim women, more so as the discourse around this case blamed only the initial act of talaq rather than the subsequent onslaughts of monetary and muscle power. The Hindu middle class imagination – even of the Socialist, Secular circles- during the 1980s and 1990s was limited, and increasingly facile. Muslim women were assumed to be the ‘victims’ of their own men – living in the constant fear of oral talaq, scurrying around mutely doing their husband’s bidding.

The reality of my extended family, however, was far away from this. Whenever my friends from Bombay visited the village of Mirjoli tucked away into the Konkani Sahyadri hills, they were struck by the boisterous women they encountered there, complete with bawdy jokes and guffawing laughter. These women hardly sat around waiting; it was common for married cousins to return home in a huff and then extended clan negotiations to ensue. In case of the ill-treatment of a married daughter or sister, a jeep full of family members would travel to her in laws, put her in the jeep and bring her back.

Marriages of divorced women with kids getting married to unmarried men were also common. Islamic tradition encouraged this as the Prophet Mohammad himself was married to Lady Khatija who was 15 years his senior and a widow. Sisters were really given shares of parental property – the half portion of the brother – again, mandated by Islamic tradition, which allowed them to retain their dignity within marriage, and more importantly, when the marriage ended.

Triple Talaq was not a practice followed by the Shafi Sunni Muslims living in the coastal regions – nor was Burkha or Hijab. This did not mean there was no patriarchy; it was evident everywhere. You could see it in the way men got the first chance at education, miscellaneous expenditure, food, sport or even entertainment. It was simply disguised differently.

… There are many Hindu realities as there are many ‘Muslim’ realities. Everywhere, women have to struggle, fight, survive. Face male domination, humiliation and irrationality of religious practices.

After I got my law degree, I spent some time in the practice of Family Law and domestic violence, particularly, organizations working with women. My foremost learning experience was in village of Andur, in the Osmanabad district of Maharashtra in tandem with the Halo Medical Foundation. Amidst this arid land and unforgiving weather conditions, I encountered harsh social situations, for women, for Dalits and for the poor. For instance, the temple entry for the Dalits and the utilization of the same water resource for all caste groups were still unresolved issues.

As a reaction to the new Domestic Violence Cell, the men would wonder, “You say not to hit the wife, Tai? Not even when she makes a mistake?” Our clients were undernourished, married much before they turned 18 and had numerous children. Sitting in on the women’s meetings in villages, I would notice bruises and enquire – the answer was typical – beatings from the husband with fists, kicks, with sickles and pipes.

Women were ‘left’ by their husbands, thrown out of their matrimonial homes and lived like vagrants at the doorstep of their brother’s household. Naila Kabeer’s ‘field of their own’ where widowed sisters would return home as daily wage labourers in their brothers’ fields came alive to me.

Poor Hindu women, despite their upper caste had no power, no property rights and no maintenance. Further, the husbands who left them would not let them go completely; in many cases, they travelled to visit the estranged wife living in a hut in the father’s village and almost righteously expected meals and sex. A network of Socialist women’s groups organized a Parityakta Parishad (Conference of Deserted women) in Aurangabad, in January 1994. They claimed that the state of Maharashtra alone had 6 lakh deserted women. Like Nafisa, these are ‘internally displaced’ women were forced to flee their habitats.

This Hindu reality was clearly distinct from the position of the professional and ambitious women within my Brahmin middle class extended family in Mumbai. Here, women competed in the job market, chose their own partners and carved out their own lives. Yet, patriarchy was around like a bad smell – as these aunts and cousins too, succumbed to domestic gender roles such as cooking and serving, and marriage rituals such as kanyadan and the change of surnames were followed unquestioned.

There are many Hindu realities as there are many ‘Muslim’ realities. Everywhere, women have to struggle, fight, survive. They face male domination, humiliation and the sheer irrationality of religious practices, and do they fight!

Nafisa is not alone. The many Nafisas are struggling against an inconceivable amount of things like her father’s broken household, the Muslim women’s groups in Bandra Golibar slums trying to contain domestic violence, the Maratha women in Andur village who serve as wage labour in the fields that should belong to them, shepherd women members of Manndeshi bank who build credit and run businesses – the count is unending. The spirit of women is still unconquered, their resilience unbound and astonishing.

This victory over oral irrevocable Talaq belongs to the poor Muslim women who went to Court to fight against custom, dogmatic male clerics and their appropriation of religious texts. They are now the torch bearers of the progressive Muslim Movement that was spear headed by Hamid Dalwai in 1960s and by the Progressive Writers’ Movement (Anjuman Tarraqi Pasand Mussanafin-e-Hind) with people like Ismat Chugtai and Manto in 1930s. Today those Muslim teachers, artisans, youth that educate, organize and agitate to seek transformation of their realities – this victory, over archaic unjust customs, belongs to them.

We cannot allow the Hindu right wing to use the Triple Talaq judgement as a tool in fueling hatred against Muslims. The plight of women is an easy gimmick to elicit in order to malign a community – the British did it with the Indians by pointing to Sati, child marriage and widow tonsuring. The Americans did it with Afghanistan by broadcasting stories of the public lynching of women. Under the garb of sympathy towards women, the aim was to vilify the men and thereby justify the military attack or colonial expansion.

Are we so naïve as to accept the claims of the Hindu right wing? Should we believe that they care about Muslim women? Can you save women from their husbands but rationalize their gang rapes? When Muslim men are killed, do Muslim women get free? The fault line does not lie between Muslim women and Muslim men, it is between those who want to stick to ascribed status – coming from patriarchy, caste superiority, religious custom – and those who seek justice. Which side are you on?